20 Oct 2012 03:23:41

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Patrick Leigh Fermor's legendary life is that it lasted as long as it did. He died in 2011 at the age of 96, having survived enough assaults on his existence to make Rasputin seem like a quitter. He was car-bombed by communists in Greece, knifed in Bulgaria, and pursued by thousands of Wehrmacht troops across Crete after kidnapping the commander of German forces on the island. Malaria, cancer and traffic accidents failed to claim him. He was the target of a long-standing Cretan blood vendetta, which did not deter him from returning to the island, though assassins waited with rifles and binoculars outside the villages he visited. He was beaten into a bloody mess by a gang of pink-coated Irish huntsmen after he asked if they buggered their foxes. He smoked 80 cigarettes a day for 30 years, and often set his bed-clothes ablaze after falling asleep with a lit fag in hand. He drank epically, and would "drown hangovers like kittens" in breakfast pints of beer and vodka. As a young SOE agent in Cairo in 1943, the centrepiece of his Christmas lunch was a turkey stuffed with Benzedrine pills; at the age of 69 he swam the Hellespont – and was nearly swept away by the current.

Yes, Leigh Fermor was an insurer's nightmare, an actuary's case-study, and his longevity was preposterous. He might best be imagined as a mixture of Peter Pan, Forrest Gump, James Bond and Thomas Browne. He was elegant as a cat, darkly handsome, unboreable, curious, fearless, fortunate, blessed with a near-eidetic memory, and surely one of the great English prose stylists of his generation.

In 1933, aged 18, he set off to walk from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople, passing through a Europe on the brink of calamity. Decades later, he published two books recounting his wander through that enshadowed land, A Time of Gifts (1977) and Between the Woods and the Water (1985). Both were instant classics, celebrated for their evocation of a since-shattered world, and for the tendrils and curlicues of their language. In between that walk and those books, Paddy (as he was mostly known) was the lover of a Romanian princess, took part in a royalist cavalry charge in Greece, parachuted into occupied Crete to co-ordinate the resistance, spent months in silent retreat in monasteries, became the most famous English Hellenophile since Byron, was played by Dirk Bogarde in a Powell and Pressburger film, and transformed travel writing.

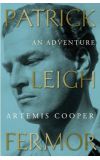

He lived an inspirationally heterodox life that combined adventure and reflection in unique measure. His story has hitherto been known only in parts, and mostly through the refractive prism of his own tellings. At last his biography has been detailed in full, in Artemis Cooper's tender and excellent book. Reading it is an odd experience: there is the melancholy of having one's hero humanised, joined with renewed astonishment at the miracle he made of himself.

For a man who would become a legend, things began inauspiciously. Feral and feckless as a child, Leigh Fermor was expelled from school after school. He was briefly happy at an experimental institution where the few timetabled activities included nude eurhythmics and country dancing. But the school was closed and the problems returned. His father, a geologist in the Raj, despaired of his wild son, and – like many despairing fathers of wild sons – signed him up for Sandhurst. Leigh Fermor reacted by moving to London, donning a lightly worn socialism, and partying hard. Indebted and unfocused, by 1933 he was – as he put it – "slowly and enjoyably disintegrating in a miniature Rake's Progress".

There the story might have ended. But on a rainy evening of "dead-beat, hungover idleness", he was seized with the idea of walking across Europe to the gates of Asia. Carousing had been his rejection of conventional education; walking would be his rejection of carousing. He kitted himself out with puttees, riding breeches and a greatcoat, somehow acquired the rucksack that Robert Byron had carried to Mount Athos, bought a walking stick of ashwood, and set off on what has been called "the longest gap year in history".

Leigh Fermor had from childhood wanted to live "with an intensity that seemed only to exist in books". This had got him into trouble in England; it was his virtue in Europe. Repeatedly he was welcomed by consuls and by counts – an adolescent super-tramp making a "country-house progress" eastwards. He walked across Bavaria in a "fairy-tale winter" of "thick, silent snow", reciting reams of poetry in five languages to himself as he went. He met entomologists, polymaths, political scientists, shepherds and aristocrats. He romped in hayricks with milk-maids, and spent a night singing in a sea-cave with fishermen, "like a flickering firelight scene out of Salvator Rosa". He was given money, transport and hospitality; he gave back charm and ebullience. "What made him so immediately engaging to people," Cooper observes, "was that he shone with joy … The greatest blessing a guest can bring to his host is the right kind of curiosity, and it bubbled out of Paddy like a natural spring."