25 Jan 2013 15:08:00

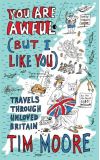

After a while, though, and as I hardened myself to the ghastliness of the surroundings, it became apparent that the book is far better than my first fears suggested. Mr Moore throws himself into his job, of travelling around the country's worst shitholes, with seriousness and dedication. He gets himself a satnav which speaks with the voice of Ozzy Osbourne (can such a thing really exist?). He installs it in an Austin Maestro, which he bought from a man called Craig. He plays, through its sound system, a selection of the worst music ever to disgrace British charts. When he writes about the "surprisingly exhaustive soundscape of the Wombles' second album", you begin to wonder whether he is damaging himself inside – although not as much as he damages his guts, as he forces himself to eat the vilest food the nation has to offer. His description of the spam fritters he forces down fairly early on, in Great Yarmouth, is a fine piece of comic writing, but not to be read if you are in the grip of a mild hangover. (Just in case you are as you read this, I shall pass on quotation.)

To deal with the comedy first: at the outset, I wondered whether he was trying too hard, or inviting us to make sport of the underprivileged. But by the time he records the description of the Maestro's engine, at speed, as sounding like "a skeleton wanking in a biscuit tin" (not his own formulation, as he decently acknowledges; this is a nation that, in the face of grisly reality, can come up with some inventive language), I was prepared to accept that the odd duff joke is worth it for all those that work. And by the end of the book he is, unlike his Maestro, firing on all cylinders.

A serious purpose emerges from this: a description of all that has gone wrong, economically, with the nation since the second world war. Or even before then – from the days when the Victorians built things to last. Nowadays, we build things that, even if they do last for more than 20 years, people beg to have knocked down almost as soon as they are erected. He portrays, for example, as extraordinarily stupid and short-sighted the way in which Hull council disposed of the millions it earned from selling its stake in the city's own telephone system (the reason it has its famous white phoneboxes). According to Moore, it managed to blow, in three years between 1999 and 2002, £263m on: a sports stadium; an aquarium with very deep tanks; and – accounting for £96m of the windfall – double-glazing the Bransholme estate, whether the houses had been lying empty for years or not, and then demolishing hundreds of them afterwards anyway.

Meanwhile it is the people's resilience that he celebrates – although he is hard-pushed for sympathy when he attempts to stay three nights at Pontins in Southport. I cannot blame him. Even without the public drunkenness of his fellow guests, his description of the interior of his room would beggar belief that such a place could be allowed to operate. The internet, and its army of outraged punters, helped him in his travels a lot. My favourite snippet from TripAdvisor went like this: "My aunt is the mayor of Rhyl, but family loyalty aside, it's the most awful place I know." From the way Moore describes the place, you suspect that the mayor's nephew is on the money, and has seen other places to compare it to. The lesson here is: this could happen to all of us. All it takes is for history to move on.