06 Mar 2013 15:17:06

Of the rest, the substance of the pages that follow, he appears to have some sympathy with his detractors, who have, he claims, variously accused him of "incest, homosexual tendencies, heterosexual debauchery, incompetence, deceit, murder, sissiness, 'carbuncular' practices, drinking too much, taking drugs and smelling bad… "

The strange thing about that particular winning pitch is the fact that the often brilliant pieces in his book often have exactly the quality of taboo-breaking private correspondence of which he suggests they have been sanitised. To discover that this is the censored version of Malan's thinking is, therefore, somewhat unnerving.

It is also a typical rhetorical device from a writer who vividly sweats blood to get somewhere near the truth, only periodically to collapse that effort and remind you of his ingrained partiality and hopelessly skewed historical vantage. In his South Africa, objectivity is generally a fool's – or a liberal's – aspiration. Malan set the pattern for this in his earlier book, in which he presented himself, at a critical historical moment, as the voice that dared not speak its name: an Afrikaans Jeremiah prophesying doom for the post-apartheid nation.

He got away with it then because his biography seemed honestly to license his pessimism. A lapsed member of the same Malan clan that created and enforced South Africa's racial divide, he had spent his working life as crime correspondent for the Johannesburg Star, reporting the brutal ways white killed black and black killed white. Try as he might, he could not imagine all that blood washed away in truth and reconciliation. Though history has so far mostly proved him wrong, he remains a doubting bitter-ender in a land of necessary hope.

Most great journalists are contrarians of one kind of another, but it would be hard to find a writer more heroically committed to that particular archetype than the 58-year-old Malan. Thus, in the name of truth, he makes the case for FW de Klerk as the true hero of 1994 and he dwells on the flaws in character and policy of Nelson Mandela; he devotes several years to disproving official Aids figures – not to argue them up, but to show them to be wilfully exaggerated to support UN policy. And along the way he convinces you that he does this not as a political but a journalistic act – he is fated to set the record straight.

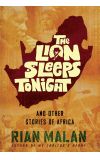

Malan is at his best when he finds a story that allows him to employ the full power of this instinctive reluctance to take yes for an answer. The stand-out pieces in this book – together more than worth the cover price – are a pair of ready-made myths from South Africa's recent history. In the first, he tracks down and moves in with the "last Afrikaner", an ancient white woman, daughter of a 1902 voortrekker, living as a subsistence farmer in the shadow of Mount Kilimanjaro, and unearths the unlikeliest tale of survival.

In the other, the title piece of this collection, he follows the money from a "haunting skein of fifteen notes" sung into a microphone in the Zulu heartland in 1939 to a multimillion-selling pop record – and 70 years on helps to restore that cash to its rightful owner. Both are stories among many here that make Malan's wider point with full force: that reporting South Africa is a long game and always hopelessly provisional. Is the rainbow nation a success story? It is, Malan would have you believe, far too early to tell.