15 Mar 2013 13:36:58

Rutherford Birchard Hayes, the 19th president of the United States of America, wakes up reincarnated as a horse. He can't understand anything, and at first mistakes the sound of his own heart for a broken stable clock, striking "upwards of twelve times, of twenty, more gongs than there were hours in a day". Already his sense of himself as human is mixed up with the perceptual world of the horse. Things will get worse. Eleven of the other horses stabled in the barn used to be US presidents too.

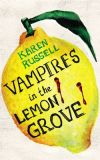

With the help of his lover, Clyde the vampire discovers himself to be a pure social construct, trapped in a culturally transmitted behaviour pattern. He takes to sucking lemons instead of people. "Instead of stalking prostitutes," he records, stunned by his own daring, "I went on long bicycle rides." But he still describes his early years "on the blood" like a junkie: someone always in recovery. He has gained a lot, but lost a lot too. He no longer needs to bite, but he's forgotten how to fly. Member of a transitional generation – not quite a monster, not quite a human being – he can be neither what he was nor what he aspires to be.

Clyde is only a case in point. The quality of being (or not quite being) monstrous proves central to most of the short stories in this, Karen Russell's second collection. But none of her monsters would be complete without a comical balancing sense of responsibility. Nal, the early-teen protagonist of "The Seagull Army Descends on Strong Beach", can't remember "the last time he acted without reservation on a single desire". Driven by the need to demonstrate their worth in the face of vague, bizarre but rigid systems, the hunger-maddened settlers of "Proving Up" accept blame for the unimprovable condition of their lives. Will the Inspector ever arrive to validate their efforts? Or is he only some desperate superego formation, a paranoid delusion of the Plains?

In "Reeling for the Empire", Kitsune, a dutiful Japanese daughter from some biopunk universe parallel to our own, is turned into a human silkworm. She's stunned by the colour of the silk she produces, but the "stench of a bad and sickening future" fills the room where she lives and works. From the bullying schoolboys of "The Graveless Doll of Eric Mutis" to the traumatised soldier of "The New Veterans", characters are beholden to fathers, mothers, siblings, partners, employers, examiners, bureaucracies; to vague and often absent principles of culture or governance. Their inner worlds are inseparable from their outer worlds – indeed, all that's left to make a distinction between the two is the author's Hipstamatic imagery and liquid prose.

Clyde the vampire describes "veiled mother-in-laws like violet spiders". In "The Seagull Army Descends on Strong Beach", the titular birds draw "a white caul over the marina", warping "people's futures into some new and terrible shapes"; while Nal's mother rumbles around her house "like its last moving part", and the "melted aluminium" of the sea ripples in front of him. Are these things really happening? Are they the surface of an object, a genuine fictional "world", something solid with which the reader can engage? Or only a dance of words and their possibilities?

More often than not, Russell rebuts any such accusation with a deft, whimsical gesture, a touch of paradoxically grounding pixie humour. False depths turn out to possess real depth after all (even in the over-extended joke that is "Dougbert Shackleton's Rules for Antarctic Tailgating").

This way of writing is so clever that nothing needs to be added to the set-up: three or four pages in, each story has already revealed its meanings, which are as subtle as the colour of Kitsune's silk. But plot becomes a problem when you write as intensely as Karen Russell.

As long as they remain apparently fragile tissues of word, image and emotion, these stories have unbelievable strength: as soon as she begins to turn them into strong narratives, they weaken and lose something. There's an effect of echo, or double vision. The two styles of communication interfere with one another, then the plot prances off with the bit between its teeth, shedding subtleties as it goes.