23 Apr 2013 02:22:27

With The Reluctant Fundamentalist, Hamid produced a thoroughly gripping and unsettling piece of "voice" writing in the first person, but the second person is a much trickier perspective to master. There's something accusatory about the narrational "you" that can sound wearyingly declarative, as though the writer were issuing a stream of instructions.

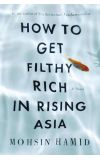

But Hamid is too deft a craftsman simply to bully the reader. Instead he seeks to create a more collusive enticement in How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia, made explicit with the conceit of a self-help guide. It's a clever idea that soon falls victim to Hamid's cleverness, as he can't seem to make up his mind if he wants to parody the genre or use it as a springboard for quasi-philosophical digressions on the "self".

The self, or the directly addressed "you" at the centre of the story, is a peasant male in some unspecified corner of Asia – although it doesn't take a lot of guesswork to identify Hamid's native Pakistan as the inspiration – whom we follow from impoverished birth through to a more comfortable death.

Given the advantage over his siblings of some basic education, he migrates to a slum in a sprawling megacity. Hamid is particularly good on the stomach-churning depths of squalor – placing the reader right inside the dank confines of the poor – and the stagnant ironies of developing nations, where teachers dream of being electricity meter readers.

With admirable determination our hero uses his street cunning and entrepreneurial instincts to work his way out of grinding destitution. He sells food with false eat-by dates and then creates his own business boiling water, bottling it in used containers and relabelling it as mineral water.

If he's a rogue trader, he's operating in a vast gallery of rogues – business competitors, police, bureaucrats, politicians – and in his case, at least, he's a lovable rogue. We warm to his pluck and his latent sense of romance as well his absence of self-pity.

There's a tremendous energy about the novel, reflected in the protagonist's unstoppable drive, but sometimes one wishes it didn't move quite so fast. Whole stages of life pass by in a few pages and given Hamid's rich descriptive skills, it's tempting to imagine a larger novel which burrowed deeper into the specificities of the central figure's struggle and environment.

That of course would be to transgress the generic aims of this work with its unnamed cities and unnamed characters. The idea is that this is what it's like for huge swaths of humanity, and here's the opportunity for the privileged reader – literacy in these circumstances is a privilege – to grasp something of the ordeal in being this anonymous "you".

But like unhappy families, all poverty is different. The corruption and religious intolerance that Hamid invokes have distinctive qualities and particular implications. It's interesting in this respect to note the debate that has recently flared concerning wholesale tax evasion among Pakistan's elite and its middle classes.

There are historical and political reasons why Pakistan is what one writer has called a "procrustean hell". And I for one would like to see Hamid bring his considerable talents to the task of examining those causes in greater detail. But perhaps that's for another time.

In this one he essays a touching love story between the protagonist and a beautiful village girl who uses her physical attributes to build her own wealth. But love is a luxury in conditions of economic struggle. The pair remain tantalisingly estranged for much of the book, only finding each other when – tellingly – they abandon their material ambitions.

If Hamid set out to write a satire on the globalised dream of consumer-driven economic development, he ends up being undermined by the strength of his characters. You can't help but root for them in their perilous climb out of the mire of penury, while all the time being relieved that you are not really "you".