18 May 2013 16:58:11

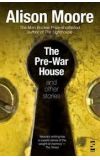

The level of accomplishment on display in this bleak narrative is remarkable. Moore is not, however, a beginner. She has been publishing short stories since 2000, and that apprenticeship shaped her first novel. Now she has published a collection of her stories, and it turns out to be just as uncompromising and unsettling as The Lighthouse.

Moore's writing has no truck with the comforts of imagined redemption. One of the features that makes The Lighthouse exceptional is its steady refusal of consolation for the hapless Futh. Nothing goes well for him. He doesn't manage as much as a decent cup of coffee throughout the entire novel, and the unfolding story of his early life makes it clear that an accumulation of sadness and incompetence has corroded his existence from its beginnings. Failure is not something to be learned from: it simply generates more disappointment, further unhappiness. This pattern is relentlessly repeated throughout The Pre-War House. A "creeping tide" of harm moves through these stories, "flooding in" as they reach their desolate conclusions.

A pared-down style allows Moore to accentuate the images that expose her characters' vulnerability. No one is safe, but the lives of children are particularly uncertain. "Chewing, I felt a milk tooth shift, and the sickening looseness in my jaw was like subsidence in my mouth." These particularities are occasionally beautiful. A lyrical passage lingers on the colour and fragility of birds' eggs – "a yellowhammer's white and purple-scribbled egg, a skylark's greyish and brown-flecked egg". More often, observations are highlighted as the signs of disturbance: "she notices the dirt and oil on her hands and a stain on her blouse". These glimpses of trouble are neither random nor decorative. Moore's strength lies in the measured control of her work: never discursive, she enacts her characters' uneasiness precisely, showing us what they see, and what they feel.

The opening story, "When the Door Closed, It Was Dark", confronts the reader with an insistent physicality, shadowed with violence. An inexperienced girl works as an au pair, homesick and evidently disliked by her employers. She is looking after a baby whose mother has disappeared, as mothers often do in these stories, for varieties of parental dysfunction lie at the centre of Moore's circles of distress. The language vibrates with foreboding: "She can hardly bear the weight she is carrying, and the rising sun beats down on her … The paintwork was bruise-coloured and blistered." The story ends with a painful jolt, but the shock is not unexpected, nor is it graphically described. The inevitability of disaster is conveyed by oblique suggestion. Moore's taut stories construct, detail by careful detail, the prisons in which her characters will be destroyed. The door closes, the darkness falls.

In this world, heavy with menace, homes are not places of safety. Moore leads her characters into enclosed domestic spaces in which they are held, willing or not, finding themselves confined rather than protected. The closing door of the opening story echoes throughout the collection, and usually it is firmly locked. Sometimes her bolder figures, like Futh, choose to venture into new places, aspiring to break out of their frustrated lives. Their ineffectual gestures leave them disoriented and defenceless. Over and over again, we leave them just before their fate is confirmed, in whatever horrifying version it may take, the reader's moment of chilled recognition coinciding with the helpless shock of the victim. There are worse things, in Moore's stories, than isolation. "You will know that you are not alone."

The ruthless manipulation of detail and design is essential to Moore's achievement, but it runs the risk of becoming oppressively formulaic, or even claustrophobic. The title story is placed last in the collection, and it exhibits all the stories' persistent characteristics – the house that becomes a place of entrapment, the vanishing mother, the eruption of violence, lost lives numbed with drink and despair. In this case, however, the final pages suggest that at least one character might find a way out. "I lock the front door behind me and walk down the driveway." This is a cheering moment in a volume where hope is hard to come by, and it briefly lifts the reader's spirits. Moore's distinctive voice commands exceptional power, and she has now reached a point where success should give her the confidence to explore different kinds of fictional freedom.