14 Jun 2013 03:09:15

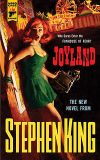

Stephen King's new novel comes in a retro-pulp cover, under the shoutline, "Who dares enter the funhouse of fear?" It's published by Hard Case Crime, whose policy is to reprint classic hardboiled fiction by writers such as Lawrence Block, Donald E Westlake and James M Cain alongside original neo-hardboiled from stars with names like Jonny Porkpie. If it isn't quite the stripped‑down tale of crime we associate with Westlake or Block, Joyland is endearingly compact – perhaps a quarter the length of a typical King – and immediately readable.

King is a genius at pulling his readers into the affective space of an ordinary central character. We feel the faintest resistance as we enter. Is "Devin Jones", who narrates the story from the other end of his life, a little bit whiny? Are his hindsight discoveries ("I'm in my sixties now, I'm a prostate cancer survivor, but I still want to know why I wasn't good enough for Wendy Keegan") a shade predictable? Yet, even as we ask these questions, we find ourselves fully acquainted with the younger Jones, 21 years old and about to have his heart broken by said Wendy. Being a student gives him context. Listening to the Small Faces, "Stay with Me", date-stamps him. He's still green, but he's earning while he's learning, in the House of Fun. We share his concerns, his fears and sympathies. We share his introduction to the carnival world, its bizarre argots and, particularly, its denizens, who suggest a promising collision between the Nick Cave of Murder Ballads and the William Lindsay Gresham of Nightmare Alley.

Lane Hardy, "a tightly muscled guy, in faded jeans", sports a derby hat which, "tilted on his coal black hair", makes him resemble "a carnival barker from an old-time newspaper strip". Madame Fortuna runs the palm-reading concession, channels Bela Lugosi, wears a shawl decorated with "various cabalistic symbols". Presiding over the carnies is the owner of Joyland, Bradley Easterbrook, old as God, "tall and amazingly thin", with enormous hands that "seem to be nothing but knuckles". Easterbrook wears a mortician's black suit and addresses his summer help thus: "Every human being … is served his or her portion of unhappiness and wakeful nights. Those of you who don't already know that will come to know it … you have been given a priceless gift this summer: you are here to sell fun."

We assume that King is offering this with a wink and a nudge while he prepares for Jones some rite of passage as harshly lit and brightly coloured as the cover of the book. Not so.

The Horror House mystery aside, Easterbrook's amusement park is without secrets. Funhouse baroque isn't even an ironic style: it's a coat of paint, underneath which is revealed the "good-natured jumble" of old-fashioned family entertainment. Fun is no longer invested in alcohol, tattoos, spitting, greasy hair, cheap thrills, fried food or socially dangerous sex on a Saturday night; in 1973 the carnies look back fondly on all those shenanigans, but they look forward with equal enthusiasm to anti-smoking legislation and increased regulation of their rides.

Above all, they provide dependable emotional support for a young adult protagonist, no longer a boy but not yet a man, who spends more of the novel assembling a transitional family, a jumping-off point for the fruitful, settled, enjoyable life of the narrating adult, than he does solving the murder of Linda Gray. A sense of family is what secures us against the dark corners, the polluted neon, the Delirium Shaker, the discarded straight-razor in a pool of blood, our "badly broken world, full of wars and cruelty and senseless tragedy". In his formative carnie summer, Devin Jones's favourite job is to put on the fur suit and entertain fractious toddlers as Howie the Happy Hound.