06 Oct 2013 04:20:42

Over the past 30 years there have been countless retellings of the Best story, several written, or at any rate offered, by Best himself. One of the most enduring is Gordon Burn's Best and Edwards (2006). This sought to define Best's place in the footballing pantheon not only by setting him alongside the Corinthian figure of Duncan Edwards, who died at 21 in the Munich air disaster, but by bringing in a second exemplar, the brooding, balding presence of Bobby Charlton – everything, in temperamental terms, that Best was not, and with whom Best didn't get on.

Charlton turns up quite a bit in Immortal: admiring Best's talent; warning "The Boss" (Sir Matt Busby) about his misdemeanours; making a final, conciliatory appearance at his deathbed. But Charlton's most arresting walk-on comes on the evening after the Wales versus the rest of the UK friendly in 1969, when Best ends up having supper at his team captain's house. As Charlton cooks the scampi, Best plies him with questions of an oddly domestic nature. Does he have a cleaner? How much did the carpet cost? Charlton deduced that Best, the serial shagger, who is once supposed to have had sex with seven women in 24 hours, was thinking of getting married.

No doubt in football, as in anything else, and to reprise Pete Townshend's often-quoted lyrics, the simple things you see are often horribly complicated, but the short sporting life and fast times of George Best (1946-2005) have never seemed particularly difficult to unravel. A politely reserved teenager from east Belfast with a prodigious natural talent breaks into professional football at precisely the moment when the rewards available to the game's finest go through the roof. He gets what he wants – fame, women, money – and then discovers that he lacks the inner resources to cope. Trying to bounce back from what looks like a mini-breakdown, he finds himself the star attraction in an ageing and weakly managed team (a superannuated Sir Matt still gamely interfering) and effectively (if not finally) retires from the business at the age of 26. There follows a protracted and well-publicised decline into a sub‑world of alcoholism, bankruptcy, liver transplants and, eventually, gruesome death.

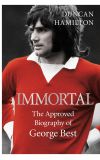

To Duncan Hamilton, an immensely astute sports writer with two William Hill sports book of the year awards to his credit, all this is the stuff of romantic legend. And, naturally, our man turns out to have hidden talents, to add to the ones already on public display. He is, for example, bookish, not boorish, has an IQ almost good enough for Mensa and is capable of taking a taxi home in search of a reference book to confirm some abstruse debating point.

The supporting cast are built up into resplendently heroic attendants. Scout, kitman and tea‑lady: there isn't a dud among them. Mrs Fullaway, his long-suffering landlady, is a saintly chatelaine. When Busby (whose indulgence of his protege's foibles is always supposed to have been the root of the trouble) compliments the teenage trainee on his ability, Best feels "as if Jesus Christ had spoken to me". The odour of sanctity is as powerful as the smell of liniment that rises from the dressing room floor.

Like many a true romance, this is at heart a masterclass in determinism (what happens does so because it has to happen) and also in teleology (what happens in the end is implicit in its beginning). Fate is much invoked: "I had a destiny," Best declared, long after the destiny had been fulfilled. But individual destinies can't work unless those collectively attached to them know their cues, and so Busby, despite convincing evidence to the contrary, always maintained that he watched Best's first training session. The odd, or perhaps inevitable, thing about Hamilton's inquiries is that the milieu is far more interesting than the subject of the legend himself. Our hero comes across as shy, diffident, courteous, a great one for the ladies and, as one whose work opportunities are rationed to 90 minutes a week, profoundly bored – who wouldn't be?

Hamilton is at his most effective when he writes of Best as an emblem of the age in which he operated: the newly liberated provincial at large in a world of fashion boutiques (several of which he owned), sexual licence and rampant consumerism. In the 1950s, as he points out, footballers had advertised such homely items as hair‑oil and shinpads. Best, under the tutelage of a canny agent named Ken Stanley, promoted everything from sausages to the Great Universal Stores catalogue (£15,000 a year in return for four afternoons' modelling). A boot deal with Stylo brought him £20,000 down, plus 5% of the retail price. The company budgeted for sales of 2,000 to 3,000 pairs in the first year; Best helped them sell 28,000.

It would be pushing things to argue that Best was a victim of the 60s – a decade that Charlton, raised in a more austere era, negotiated with only the loss of his hair – but there hangs over Hamilton's book the terrific sense of a personality on a collision course with an environment that seemed calculated to destroy him. Meanwhile, the clouds of glory go floating by ("His goal is gorgeous, and he unfurls it like a bolt of gold-threaded silk."). You can't help concluding that football itself is an endlessly fascinating spectacle, but the majority of professional footballers are not.