22 Oct 2010 00:24:32

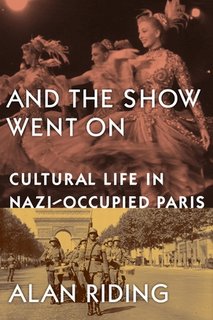

During the four years of World War II in which France was under Nazi occupation, artists painted; musicians and singers performed; fashion designers turned out haute couture; and novelists, poets and playwrights produced work at a pace that reflected the City of Light's renown as a cultural beacon and a place where intellectuals were held in high esteem. As author Alan Riding explains in "And the Show Went On," his broad-ranging book about cultural life during the occupation, it was in the interest of conqueror and vanquished alike that such pursuits be allowed to continue. For the German occupiers, the cultural activities offered a distraction for the Parisians and themselves; the French kept their culture alive, which provided a source of pride after the crushing defeat of their once-vaunted military.

The book includes solid examinations of the prewar and postwar cultural milieu, but the heart of Riding's work focuses on how many of the leading figures in the arts and letters coped with life under the Third Reich.

Some writers with Fascist leanings applauded the 1940 outcome and collaborated with the Nazis. A handful were executed in a spasm of vengeance that followed the liberation four years later, but others had their prison sentences commuted during the postwar period as the French sought to minimize the extent of such collaboration.

Louis-Ferdinand Celine, regarded as one of the greatest French writers of the 20th century, had fled to Denmark amid accusations of treason but was later granted amnesty. He returned to France and was back in business with his old publisher. "For many French citizens, his pro-Nazi and anti-Semitic delirium was simply overshadowed by his genius," writes Riding, a longtime European cultural correspondent for The New York Times.

Edith Piaf and Maurice Chevalier performed in Germany during the war, but those visits put barely a dent in their postwar popularity. Others, such as Jean-Paul Sartre, sought to burnish their images by insisting that their writings during the occupation were intended to promote resistance.

There were some heroes and martyrs among writers: Andre Malraux joined the armed resistance in the months prior to liberation and some lesser known figures risked their lives by their clandestine publication of anti-Nazi newspapers, protection of Jewish writers and artists, and aid to British troops fleeing France during their retreat.

Despite small cadres of collaborators and resisters, the vast majority of artists, writers and musicians simply labored as best they could in an abnormal situation in which their work was subject to censorship. These so-called "attentistes," who sought to make the best of a bad situation, occasionally showed up at dinners and receptions at the German embassy, but Riding suggests that such visits may have been motivated by an opportunity for good food and wine that was otherwise scarce.

Riding catalogs the prodigious output of all cultural endeavors and details the fascinating characters and stories of the arts scene during the occupation. There is the salon of the wealthy American Florence Gould, a weekly soiree that drew Paris' leading literary figures. For film buffs, the steamy affair between leading lady Danielle Darrieux and Latin-American diplomat-playboy Porfirio Rubirosa provided grist for movie magazines.

The book includes solid examinations of the prewar and postwar cultural milieu, but the heart of Riding's work focuses on how many of the leading figures in the arts and letters coped with life under the Third Reich.

Some writers with Fascist leanings applauded the 1940 outcome and collaborated with the Nazis. A handful were executed in a spasm of vengeance that followed the liberation four years later, but others had their prison sentences commuted during the postwar period as the French sought to minimize the extent of such collaboration.

Louis-Ferdinand Celine, regarded as one of the greatest French writers of the 20th century, had fled to Denmark amid accusations of treason but was later granted amnesty. He returned to France and was back in business with his old publisher. "For many French citizens, his pro-Nazi and anti-Semitic delirium was simply overshadowed by his genius," writes Riding, a longtime European cultural correspondent for The New York Times.

Edith Piaf and Maurice Chevalier performed in Germany during the war, but those visits put barely a dent in their postwar popularity. Others, such as Jean-Paul Sartre, sought to burnish their images by insisting that their writings during the occupation were intended to promote resistance.

There were some heroes and martyrs among writers: Andre Malraux joined the armed resistance in the months prior to liberation and some lesser known figures risked their lives by their clandestine publication of anti-Nazi newspapers, protection of Jewish writers and artists, and aid to British troops fleeing France during their retreat.

Despite small cadres of collaborators and resisters, the vast majority of artists, writers and musicians simply labored as best they could in an abnormal situation in which their work was subject to censorship. These so-called "attentistes," who sought to make the best of a bad situation, occasionally showed up at dinners and receptions at the German embassy, but Riding suggests that such visits may have been motivated by an opportunity for good food and wine that was otherwise scarce.

Riding catalogs the prodigious output of all cultural endeavors and details the fascinating characters and stories of the arts scene during the occupation. There is the salon of the wealthy American Florence Gould, a weekly soiree that drew Paris' leading literary figures. For film buffs, the steamy affair between leading lady Danielle Darrieux and Latin-American diplomat-playboy Porfirio Rubirosa provided grist for movie magazines.