01 Mar 2011 03:19:56

This book isn't funny book about anything. It is a book that full insightful conclusions that summarize you to new thoughts. It isn't easy to fight with hard situation, but not to fight - it is more harder and frightener.

Achatz decided to reject treatment. Even if he survived, he wouldn't have a life he wanted. He couldn't be a chef without a tongue; he couldn't cook if he couldn't taste.

It many ways, it was his business partner who saved him. Nick Kokonas researched treatments and pushed Achatz to see specialist after specialist. Then he turned to the media. An article in the Chicago Tribune got Achatz into a pioneering program at the University of Chicago, where doctors used chemotherapy and radiation to shrink the tumor before surgery, making it possible to save the chef's tongue and his life.

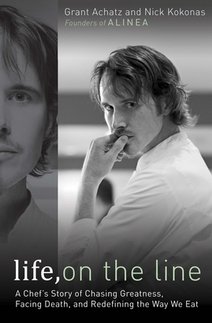

Achatz and Kokonas recount his battle with cancer in "Life, on the Line," which is nearly certain to be one of this year's top-selling food memoirs. Achatz already has a strong following among foodies. Gourmet magazine named his Chicago restaurant Alinea the best in the nation in 2006, and Achatz received the James Beard Foundation's award for outstanding chef in 2008. His story also is sure to win a following among cancer survivors and those battling the disease.

But don't let that keep you from reading the book. This is an autobiography that rises above both those genres. Achatz's story is a compelling tale of artistic genius that will make you cry and, if you are in the Chicago area, perhaps shell out $200 a person to eat his food.

"Life" starts, as Achatz's did, with his childhood in a small town in nowhere Michigan. His parents owned a restaurant and Achatz, an only child, grew up cooking. By high school, when his best friend was dreaming of flying fighter jets, Achatz had only one goal — to own a great restaurant.

Achatz had the requisite work ethic and self-confidence bordering on arrogance. He graduated from the world-renowned Culinary Institute of America, where he found the other students lacking in dedication. Then he spent a few months being berated in the kitchen of the legendary Charlie Trotter.

He couldn't take it. Achatz writes, "I wanted one-on-one time and mentoring. ... but instead I got ass-kickings."

The passage is notable because Achatz later dresses down some of his own chefs in what seems to be a similar fashion. This is not a guy who will always warm your heart.

Achatz found his mentor in Thomas Keller of Napa Valley's The French Laundry, went on to overhaul Trio in suburban Chicago and then created Alinea as part of a wave of chefs interested in molecular gastronomy — the application of scientific techniques to cooking.

He opened Alinea with Kokonas, a derivatives trader who retired in his 30s and had been a regular at Trio for years. The latter part of "Life" is told from both their perspectives, and while the transition is jarring at first because you've dropped so deep into Achatz's psyche, the second voice lends a welcome dimension to the story. While Achatz withdrew into himself during his fight with cancer, Kokonas kept things going. He recounts how the chef's illness affected everyone around him.

Achatz is the kind of artist who sinks everything into his work. He writes about neglecting his ex-girlfriend, with whom he had two children, and his gratitude that his first son was born on a day the restaurant was closed. Again, not very heartwarming.

But, such things might be forgiven in a great artist consumed by his vision, and Achatz certainly seems to be that. One of the most impressive aspects of "Life" is the way in which he leads the reader along the train of thought that produced a great dish.

"I remembered the wine glasses breaking," he writes, "and the smell of the raspberries. And just like that it happens. Raspberries are fragile like fine glassware, maybe even clear like stained glass. They smell like roses, so we'll pair them with roses."

Achatz decided to reject treatment. Even if he survived, he wouldn't have a life he wanted. He couldn't be a chef without a tongue; he couldn't cook if he couldn't taste.

It many ways, it was his business partner who saved him. Nick Kokonas researched treatments and pushed Achatz to see specialist after specialist. Then he turned to the media. An article in the Chicago Tribune got Achatz into a pioneering program at the University of Chicago, where doctors used chemotherapy and radiation to shrink the tumor before surgery, making it possible to save the chef's tongue and his life.

Achatz and Kokonas recount his battle with cancer in "Life, on the Line," which is nearly certain to be one of this year's top-selling food memoirs. Achatz already has a strong following among foodies. Gourmet magazine named his Chicago restaurant Alinea the best in the nation in 2006, and Achatz received the James Beard Foundation's award for outstanding chef in 2008. His story also is sure to win a following among cancer survivors and those battling the disease.

But don't let that keep you from reading the book. This is an autobiography that rises above both those genres. Achatz's story is a compelling tale of artistic genius that will make you cry and, if you are in the Chicago area, perhaps shell out $200 a person to eat his food.

"Life" starts, as Achatz's did, with his childhood in a small town in nowhere Michigan. His parents owned a restaurant and Achatz, an only child, grew up cooking. By high school, when his best friend was dreaming of flying fighter jets, Achatz had only one goal — to own a great restaurant.

Achatz had the requisite work ethic and self-confidence bordering on arrogance. He graduated from the world-renowned Culinary Institute of America, where he found the other students lacking in dedication. Then he spent a few months being berated in the kitchen of the legendary Charlie Trotter.

He couldn't take it. Achatz writes, "I wanted one-on-one time and mentoring. ... but instead I got ass-kickings."

The passage is notable because Achatz later dresses down some of his own chefs in what seems to be a similar fashion. This is not a guy who will always warm your heart.

Achatz found his mentor in Thomas Keller of Napa Valley's The French Laundry, went on to overhaul Trio in suburban Chicago and then created Alinea as part of a wave of chefs interested in molecular gastronomy — the application of scientific techniques to cooking.

He opened Alinea with Kokonas, a derivatives trader who retired in his 30s and had been a regular at Trio for years. The latter part of "Life" is told from both their perspectives, and while the transition is jarring at first because you've dropped so deep into Achatz's psyche, the second voice lends a welcome dimension to the story. While Achatz withdrew into himself during his fight with cancer, Kokonas kept things going. He recounts how the chef's illness affected everyone around him.

Achatz is the kind of artist who sinks everything into his work. He writes about neglecting his ex-girlfriend, with whom he had two children, and his gratitude that his first son was born on a day the restaurant was closed. Again, not very heartwarming.

But, such things might be forgiven in a great artist consumed by his vision, and Achatz certainly seems to be that. One of the most impressive aspects of "Life" is the way in which he leads the reader along the train of thought that produced a great dish.

"I remembered the wine glasses breaking," he writes, "and the smell of the raspberries. And just like that it happens. Raspberries are fragile like fine glassware, maybe even clear like stained glass. They smell like roses, so we'll pair them with roses."