Adams Samuel

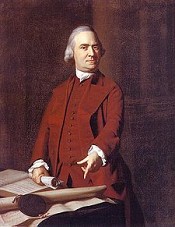

Samuel Adams (September 27 [O.S. September 16] 1722 – October 2, 1803) was a statesman, political philosopher, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. As a politician in colonial Massachusetts, Adams was a leader of the movement that became the American Revolution, and was one of the architects of the principles of American republicanism that shaped the political culture of the United States. He was a second cousin to John Adams. Born in Boston, Adams was brought up in a religious and politically active family. A graduate of Harvard College, he was an unsuccessful businessman and tax collector before concentrating on politics. As an influential official of the Massachusetts House of Representatives and the Boston Town Meeting in the 1760s, Adams was a part of a movement opposed to the British Parliament's efforts to tax the British American colonies without their consent. His 1768 circular letter calling for colonial cooperation prompted the occupation of Boston by British soldiers, eventually resulting in the Boston Massacre of 1770. To help coordinate resistance to what he saw as the British government's attempts to violate the British Constitution at the expense of the colonies, in 1772 Adams and his colleagues devised a committee of correspondence system, which linked like-minded Patriots throughout the Thirteen Colonies. Continued resistance to British policy resulted in the 1773 Boston Tea Party and the coming of the American Revolution. After Parliament passed the Coercive Acts in 1774, Adams attended the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, which was convened to coordinate a colonial response. He helped guide Congress towards issuing the Declaration of Independence in 1776, and helped draft the Articles of Confederation and the Massachusetts Constitution. Adams returned to Massachusetts after the American Revolution, where he served in the state senate and was eventually elected governor. Samuel Adams is a controversial figure in American history. Accounts written in the 19th century praised him as someone who had been steering his fellow colonists towards independence long before the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. This view gave way to negative assessments of Adams in the first half of the 20th century, in which he was portrayed as a master of propaganda who provoked mob violence to achieve his goals. Both of these interpretations have been challenged by some modern scholars, who argue that these traditional depictions of Adams are myths contradicted by the historical record. Samuel Adams was born in Boston in the British colony of Massachusetts on September 16, 1722, an Old Style date that is sometimes converted to the New Style date of September 27.[3] Adams was one of twelve children born to Samuel Adams, Sr., and Mary (Fifield) Adams; in an age of high infant mortality, only three of these children would live past their third birthday.[4] Adams's parents were devout Puritans, and members of the Old South Congregation Church. The family lived on Purchase Street in Boston.[5] Adams was proud of his Puritan heritage, and emphasized Puritan values, especially virtue, in his political career.[6] Samuel Adams, Sr. (1689–1748) was a prosperous merchant and church deacon.[7] Deacon Adams became a leading figure in Boston politics through an organization that became known as the Boston Caucus, which promoted candidates who supported popular causes.[8] The Boston Caucus helped shape the agenda of the Boston Town Meeting. A New England town meeting is a form of local government with elected officials, and not just a gathering of citizens; it was, according to historian William Fowler, "the most democratic institution in the British empire".[9] Deacon Adams rose through the political ranks, becoming a justice of the peace, a selectman, and a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives.[10] He worked closely with Elisha Cooke, Jr. (1678–1737), the leader of the "popular party", a faction that resisted any encroachment by royal officials on the colonial rights embodied in the Massachusetts Charter of 1691.[11] In the coming years, members of the "popular party" would become known as Whigs or Patriots.[12] The younger Samuel Adams attended Boston Latin School and then entered Harvard College in 1736. His parents hoped that his schooling would prepare him for the ministry, but Adams gradually shifted his interest to politics.[14] After graduating in 1740, Adams continued his studies, earning a master's degree in 1743. His thesis, in which he argued that it was "lawful to resist the Supreme Magistrate, if the Commonwealth cannot otherwise be preserved", indicated that his political views, like his father's, were oriented towards colonial rights.[15] Adams's life was greatly affected by his father's involvement in a banking controversy. In 1739, with Massachusetts facing a serious currency shortage, Deacon Adams and the Boston Caucus created a "land bank", which issued paper money to borrowers who mortgaged their land as security.[16] The land bank was generally supported by the citizenry and the popular party, which dominated the House of Representatives, the lower branch of the General Court. Opposition to the land bank came from the more aristocratic "court party", who were supporters of the royal governor and controlled the Governor's Council, the upper chamber of the General Court.[17] The court party used its influence to have the British Parliament dissolve the land bank in 1741.[18] Directors of the land bank, including Deacon Adams, became personally liable for the currency still in circulation, payable in silver and gold. Lawsuits over the bank persisted for years, even after Deacon Adams's death, and the younger Samuel Adams would often have to defend the family estate from seizure by the government.[19] For Adams, these lawsuits "served as a constant personal reminder that Britain's power over the colonies could be exercised in arbitrary and destructive ways".[20] After leaving Harvard in 1743, Adams was unsure about his future. He considered becoming a lawyer, but instead decided to go into business. He worked at Thomas Cushing's counting house, but the job only lasted a few months because Cushing felt that Adams was too preoccupied with politics to become a good merchant.[21] Adams's father then loaned him £1,000 to go into business for himself, a substantial amount for that time.[22] Adams's lack of business instincts were confirmed: he loaned half of this money to a friend, which was never repaid, and frittered away the other half. Adams would always remain, in the words of historian Pauline Maier, "a man utterly uninterested in either making or possessing money".[23] Having lost his money, Adams's father made him a partner in the family's malthouse, which was next to the family home on Purchase Street. Several generations of Adamses were maltsters, who produced the malt necessary for brewing beer.[25] Years later, a poet would poke fun at Adams by calling him "Sam the maltster".[26] Adams has often been described as a brewer, but the extant evidence suggests that Adams worked as a maltster and not a brewer.[27] In January 1748, Adams and some friends, inflamed by British impressment, launched the Independent Advertiser, a weekly newspaper that printed many political essays written by Adams.[28] Drawing heavily upon English political theorist John Locke's Second Treatise of Government, Adams's essays emphasized many of the themes that would characterize his subsequent career.[29] He argued that the people must resist any encroachment on their constitutional rights.[30] He cited the decline of the Roman Empire as an example of what could happen to New England if it were to abandon its Puritan values.[31] When Deacon Adams died in 1748, Adams was given the responsibility of managing the family's affairs.[32] In October 1749, he married Elizabeth Checkley, his pastor's daughter.[33] Elizabeth gave birth to six children over the next seven years, but only two—Samuel (born 1751) and Hannah (born 1756)—would live to adulthood.[34] In July 1757, Elizabeth died soon after giving birth to a stillborn son.[35] Adams would remarry in 1764, to Elizabeth Wells,[36] but would have no other children.[23] Like his father, Adams embarked on a political career with the support of the Boston Caucus. He was elected to his first political office in 1747, serving as one of the clerks of the Boston market. In 1756 the Boston Town Meeting elected him to the post of tax collector, which provided a small income.[37] Adams often failed to collect taxes from his fellow citizens, which increased his popularity among those who did not pay, but left him liable for the shortage.[38] By 1765, Adams's account was more than £8,000 in arrears. Because the town meeting was on the verge of bankruptcy, Adams was compelled to file suit against delinquent taxpayers, but many taxes went uncollected.[39] In 1768, Adams's political opponents would use the situation to their advantage, obtaining a court judgment of £1,463 against him. Adams's friends paid off some of the deficit, and the town meeting wrote off the remainder. By then, Adams had emerged as a leader of the popular party, and the embarrassing situation did not lessen his influence.[40] Samuel Adams emerged as an important public figure in Boston soon after the British Empire's victory in the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). Finding itself deep in debt and looking for new sources of revenue, the British Parliament sought, for the first time, to directly tax the colonies of British America.[41] This tax dispute was part of a larger divergence between British and American interpretations of the British Constitution and the extent of Parliament's authority in the colonies.[42] The first step in the new program was the Sugar Act of 1764. Adams saw the act as an infringement of longstanding colonial rights. Because colonists were not represented in Parliament, he argued, they could not be taxed by that body; only the colonial assemblies, where the colonists were represented, could levy taxes upon the colonies.[43] Adams expressed these views in May 1764, when the Boston Town Meeting elected its representatives to the Massachusetts House. As was customary, the town meeting provided the representatives with a set of written instructions, which Adams was selected to write. Adams highlighted what he perceived to be the dangers of taxation without representation:

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

the writings of samuel adams volume 1

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

1.5/5

Collection of works by Samuel Adams, an eighteenth century statesman, political philosopher, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. Harry Alfonzo Gushing, who collected and edited the volume, says: The writings of no one of the leaders of the American Revolution form a more complete expression of the causes and justification of that movement than do those of Samuel Adams. None of his contemporaries was so closely identified with the agitation which preceded that crisis, or displayed at that time greater facility as a writer or more unqualified devotion to public affairs. In both the politics and the literature of the American Revolution his writings constitute a distinct and essential element.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Writings of Samuel Adams - Volume 4

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

The documents and correspondence of the great American patriot. These texts begin with Adams' efforts to rally public protest over the Sugar and Stamp Acts (1764-65), and continues as he becomes an outspoken critic of English policies, fanning the flames of public unrest which erupt into violence in the Boston Massacre in 1770. The Boston Tea Party, Adams' narrow escape from the British forces at Lexington, membership in the First and Second Continental Congress, signing the Declaration of Independence, serving as a member of Congress throughout the Revolutionary War, and finally as Governor of Massachusetts--all are documented in this unique collection.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Writings of Samuel Adams - Volume 3

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Covering the years 1773-1777.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

the writings of samuel adams volume 1

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

1.5/5

Collection of works by Samuel Adams, an eighteenth century statesman, political philosopher, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. Harry Alfonzo Gushing, who collected and edited the volume, says: The writings of no one of the leaders of the American Revolution form a more complete expression of the causes and justification of that movement than do those of Samuel Adams. None of his contemporaries was so closely identified with the agitation which preceded that crisis, or displayed at that time greater facility as a writer or more unqualified devotion to public affairs. In both the politics and the literature of the American Revolution his writings constitute a distinct and essential element.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Writings of Samuel Adams - Volume 4

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

The documents and correspondence of the great American patriot. These texts begin with Adams' efforts to rally public protest over the Sugar and Stamp Acts (1764-65), and continues as he becomes an outspoken critic of English policies, fanning the flames of public unrest which erupt into violence in the Boston Massacre in 1770. The Boston Tea Party, Adams' narrow escape from the British forces at Lexington, membership in the First and Second Continental Congress, signing the Declaration of Independence, serving as a member of Congress throughout the Revolutionary War, and finally as Governor of Massachusetts--all are documented in this unique collection.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Writings of Samuel Adams - Volume 3

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Covering the years 1773-1777.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Writings of Samuel Adams - Volume 2

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Where then is the honor! where is the shame of these persons, who can look into the faces of those very men with whom they have contracted, & tell them Without Blushing that they are resolved to Violate the contract!

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Adams Samuel try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Adams Samuel try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!