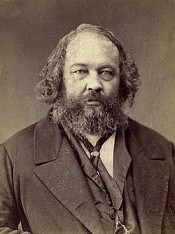

Bakunin Mikhail

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (30 May [O.S. 18 May] 1814 - 1 July, 1876) (Russian: Михаи́л Алекса́ндрович Баку́нин) was a well-known Russian revolutionary and theorist of collectivist anarchism.[1] Born in the Russian Empire to a family of Russian nobles, Bakunin spent his youth as a junior officer in the Russian army but resigned his commission in 1835. He went to school in Moscow to study philosophy and began to frequent radical circles where he was greatly influenced by Alexander Herzen. Bakunin left Russia in 1842 for Dresden, and eventually arrived in Paris, where he met George Sand, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Karl Marx. He was eventually deported from France for speaking against Russia's oppression of Poland. In 1849 he was apprehended in Dresden for his participation in the Czech rebellion of 1848. He was turned over to Russia where he was imprisoned in Peter-Paul Fortress in Saint Petersburg. He remained there until 1857, when he was exiled to a work camp in Siberia. He was able to escape via Japan and the USA, and ended up in London for a short time, where he worked with Herzen on the radical journal Kolokol ("The Bell"). In 1863, he left to join the insurrection in Poland, but he failed to reach his destination and spent some time in Switzerland and Italy. Despite his criminal status, Bakunin gained great influence with radical youth in Russia, and all of Europe. In 1870, he was involved in the insurrection in Lyon, which foreshadowed the Paris Commune. In 1868, Bakunin joined the International Working Men's Association, a federation of radical and trade union organizations with sections in most European countries. The 1872 Congress was dominated by a fight between a faction around Marx who argued for participation in parliamentary elections and a faction around Bakunin who opposed it. Bakunin's faction lost the vote on this issue, and at the end of the congress, Bakunin and several of his faction were expelled for supposedly maintaining a secret organisation within the international. The anarchists insisted the congress was rigged, and so held their own conference of the International at Saint-Imier in Switzerland in 1872. Bakunin remained very active in this and the European socialist movement. From 1870 to 1876, he wrote much of his seminal work such as Statism and Anarchy and God and the State. Despite his declining health, he tried to take part in an insurrection in Bologna, but was forced to return to Switzerland in disguise, and settled in Lugano. He remained active in the radical movement of Europe until further health problems caused him to be moved to a hospital in Berne, where he died in 1876. Bakunin is remembered as a major figure in the history of anarchism and an opponent of Marxism, especially of Marx's idea of dictatorship of the proletariat. He continues to be an influence on modern-day anarchists, such as Noam Chomsky.[2] In the spring of 1814, Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin was born to an aristocratic family in the village of Pryamukhino (Прямухино) between Torzhok (Торжок) and Kuvshinovo (Кувшиново), in Tver guberniya, northwest of Moscow. At the age of 14 he left for Saint Petersburg, receiving military training at the Artillery University. He completed his studies in 1832, and in 1834 was commissioned a junior officer in the Russian Imperial Guard and sent to Minsk and Gardinas in Lithuania (now Belarus). That summer, Bakunin became embroiled in a family row, taking his sister’s side in rebellion to an unhappy marriage. Though his father wished him to continue in either the military or the civil service, Bakunin abandoned both in 1835, and made his way to Moscow, hoping to study philosophy. In Moscow, Bakunin soon became friends with a group of former university students, and engaged in the systematic study of Idealist philosophy, grouped around the poet Nikolay Stankevich, “the bold pioneer who opened to Russian thought the vast and fertile continent of German metaphysics” (E. H. Carr). The philosophy of Kant initially was central to their study, but then progressed to Schelling, Fichte, and Hegel. By autumn of 1835, Bakunin had conceived of forming a philosophical circle in his home town of Pryamukhino; a passionate environment for the young people involved. For example, Vissarion Belinsky fell in love with one of Bakunin’s sisters. Moreover, by early 1836, Bakunin was back in Moscow, where he published translations of Fichte’s Some Lectures Concerning the Scholar's Vocation and The Way to a Blessed Life, which became his favorite book. With Stankevich he also read Goethe, Schiller, and E.T.A. Hoffmann. At this time he embraced a religious but extra-ecclesiastical immanentism: … Because we have baptized in this world and are in communion with this heavenly love, we feel that we are divine creatures, that we are free, and that we have been ordained for the emancipation of humanity, which has remained a victim of the instinctive laws of unconscious existence. … Absolute freedom and absolute love—that is our aim; the freeing of humanity and the whole world–that is our purpose. He became increasingly influenced by Hegel and provided the first Russian translation of his work. During this period he met slavophile Konstantin Aksakov, Piotr Tschaadaev and the socialists Alexander Herzen and Nikolay Ogarev. In this period he began to develop his panslavic views. After long wrangles with his father, Bakunin went to Berlin in 1840. His stated plan at the time was still to become a university professor (a “priest of truth,” as he and his friends imagined it), but he soon encountered and joined radical students of the so-called “Hegelian Left,” and joined the socialist movement in Berlin. In his 1842 essay The Reaction in Germany, he argued in favor of the revolutionary role of negation, summed up in the phrase After three semesters in Berlin, Bakunin went to Dresden where he became friends with Arnold Ruge. Here he also read Lorenz von Stein's Der Sozialismus und Kommunismus des heutigen Frankreich and developed a passion for socialism. He abandoned his interest in an academic career, devoting more and more of his time to promoting revolution.The Russian government, becoming aware of his radicalism, ordered him to return to Russia. On his refusal his property was confiscated. Instead he went with Georg Herwegh to Zürich, Switzerland. During his six month stay in Zürich, he became closely associated with German communist Wilhelm Weitling. Until 1848 he remained on friendly terms with the German communists, occasionally calling himself a communist and writing articles on communism in the Schweitzerische Republikaner. He moved to Geneva in western Switzerland shortly before Weitling's arrest. His name had appeared frequently in Weitling's correspondence seized by the police. This led to reports being circulated to the imperial police. The Russian ambassador in Berne ordered Bakunin to return to Russia, but instead he went to Brussels, where he met many leading Polish nationalists, such as Joachim Lelewel, co-member with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels at Brussels. Lelewel greatly influenced him, however he clashed with the Polish nationalists over their demand for a historic Poland based on the borders of 1776 (before the Partitions of Poland) as he defended the right of autonomy for the non-Polish peoples in these territories. He also did not support their clericalism and they did not support his calls for the emancipation of the peasantry. In 1844 Bakunin went to Paris, then a centre for European radicalism. He established contacts with Karl Marx and the anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who greatly impressed him and with whom he formed a personal bond. In December 1844, Emperor Nicholas issued a decree stripping Bakunin of his privileges as a noble, denying him civil rights, confiscating his land in Russia, and condemning him to life long exile in Siberia should the Russian authorities ever get their hands on him. He responded with a long letter to La Réforme, denouncing the Emperor as a despot and calling for democracy in Russia and Poland (Carr, p. 139). In March 1846 in another letter to the Constitutionel he defended Poland, following the repression of Catholics there. Some Polish refugees from Kraków, following the defeat of the uprising there, invited him to speak[4] at the meeting in November 1847 commemorating the Polish November Uprising of 1830. In his speech, Bakunin called for an alliance between the Polish and Russian peoples against the Emperor, and looked forward to "the definitive collapse of despotism in Russia." As a result, he was expelled from France and went to Brussels. Bakunin's attempt to draw Alexander Herzen and Vissarion Belinsky into conspiratorial action for revolution in Russia fell on deaf ears. In Brussels, Bakunin renewed his contacts with revolutionary Poles and Karl Marx. He spoke at a meeting organised by Lelewel in February 1848 about a great future for the slavs, whose destiny was to rejuvenate the Western world. Around this time the Russian embassy circulated rumours that Bakunin was a Russian agent who had exceeded his orders. As the revolutionary movement of 1848 broke out, Bakunin was ecstatic, despite disappointment that little was happening in Russia. Bakunin obtained funding from some socialists in the Provisional Government, Ferdinand Flocon, Louis Blanc, Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin and Albert L'Ouvrier, for a project for a Slav federation liberating those under the rule of Prussia, Austro-Hungary and Turkey. He left for Germany travelling through Baden to Frankfurt and Köln. Bakunin supported the German Democratic Legion led by Herwegh in an abortive attempt to join Friedrich Hecker's insurrection in Baden. He broke with Marx over the latter's criticism of Herwegh. Much later in 1871 – Bakunin was to write: “I must openly admit that in this controversy Marx and Engels were in the right. With characteristic insolence, they attacked Herwegh personally when he was not there to defend himself. In a face-to-face confrontation with them, I heatedly defended Herwegh, and our mutual dislike began then.”[5]

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

God and the State

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

He is remembered as one of the originators of modern anarchy, a foe to Marx, and a radicalizer of youth through Russia and Europe in the 19th century. His name has been honored by pop culture of late in Tom Stoppard's trilogy of plays The Coast of Utopia, and on the philosophical playground of TV's Lost, which features characters named for-and often interpreted to represent the thinking of-famous philosophers through history. He is Russian revolutionary MIKHAIL ALEXANDROVICH BAKUNIN (1814-1876), and God and the State is his only published work. Unfinished at the time of his death and rambling and disjointed at best, this is nevertheless a provocative exploration of Bakunin's ideas on the enslavement of humanity by religion, its use by the state as a weapon against the people, and the necessity of throwing off the chains of God-worship. It remains a vital document of the anarchist movement, and is essential reading for anyone wishing to understand the upheavals of 19th-century Russia.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

God and the State

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

He is remembered as one of the originators of modern anarchy, a foe to Marx, and a radicalizer of youth through Russia and Europe in the 19th century. His name has been honored by pop culture of late in Tom Stoppard's trilogy of plays The Coast of Utopia, and on the philosophical playground of TV's Lost, which features characters named for-and often interpreted to represent the thinking of-famous philosophers through history. He is Russian revolutionary MIKHAIL ALEXANDROVICH BAKUNIN (1814-1876), and God and the State is his only published work. Unfinished at the time of his death and rambling and disjointed at best, this is nevertheless a provocative exploration of Bakunin's ideas on the enslavement of humanity by religion, its use by the state as a weapon against the people, and the necessity of throwing off the chains of God-worship. It remains a vital document of the anarchist movement, and is essential reading for anyone wishing to understand the upheavals of 19th-century Russia.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Bakunin Mikhail try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Bakunin Mikhail try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!