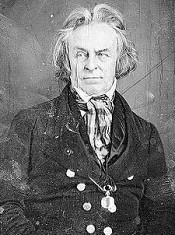

Calhoun John Caldwell

John Caldwell Calhoun (March 18, 1782 – March 31, 1850) was the seventh Vice President of the United States and a leading Southern politician from South Carolina during the first half of the 19th century. Calhoun was an advocate of slavery, states' rights, limited government, and nullification. He was the second man to serve as Vice President under two administrations (as a Democratic-Republican under John Quincy Adams and as a Democrat under Andrew Jackson), the first Vice President to have been born after the American Revolution, and the first Vice President to resign from office. Calhoun briefly served in the South Carolina legislature. There he wrote legislation making South Carolina the first state to adopt universal suffrage for white men. Although Calhoun died nearly 11 years before the start of the American Civil War, he was an advocate of secession. Nicknamed the "cast-iron man" for his determination to defend the causes in which he believed, Calhoun supported state's rights and nullification, under which states could declare null and void federal laws which they deemed to be unconstitutional. He was an outspoken proponent of the institution of slavery, which he famously defended as a "positive good" rather than as a "necessary evil".[2] His rhetorical defense of slavery was partially responsible for escalating Southern threats of secession in the face of mounting abolitionist sentiment in the North. Calhoun was one of the "Great Triumvirate" or the "Immortal Trio" of statesmen, along with his Congressional colleagues Daniel Webster and Henry Clay. Calhoun served in the House of Representatives (1810–1817) and the United States Senate (1832–1843). He was appointed Secretary of War (1817–1824) under James Monroe and Secretary of State (1844–1845) under John Tyler. Calhoun was born on March 18, 1782, the fourth child of Patrick Calhoun and his wife Martha (née Caldwell). His father was an Ulster-Scot who emigrated from County Donegal to the Thirteen Colonies where he met Martha, daughter of a Protestant Scots-Irish immigrant father [3]. When his father became ill, the 17-year-old Calhoun quit school to work on the family farm. With his brothers' financial support, he later returned to his studies, earning a degree from Yale College, Phi Beta Kappa,[4] in 1804. After studying law at the Tapping Reeve Law School in Litchfield, Connecticut, Calhoun was admitted to the South Carolina bar in 1807. In January 1811, Calhoun married Floride Bonneau Colhoun, a first cousin once removed. Her branch of the family spelled the surname differently than did his. The couple had 10 children over 18 years; three died in infancy. During her husband's second term as Vice President, Floride Calhoun was a central figure in the Petticoat affair. In 1810, Calhoun was elected to Congress, and became one of the War Hawks. Led by Henry Clay, they argued for what became the War of 1812. Calhoun made his public debut in calling for war after the Chesapeake-Leopard affair in 1807. After the war, Calhoun and Clay sponsored a Bonus Bill for public works. With the goal of building a strong nation that could fight future wars, Calhoun aggressively pushed for high protective tariffs (to build up industry), a national bank, internal improvements, and many other policies he later repudiated.[clarification needed][5] In 1817, President James Monroe appointed Calhoun Secretary of War, where he served until 1825. Belko (2004) argues that Calhoun's actions in this capacity proved his nationalism. His opponents were the "Old Republicans" in Congress, with their Jeffersonian ideology for economy in the federal government; they often attacked the operations and finances of the War Department. Calhoun was a reform-minded executive, who attempted to institute centralization and efficiency in the Indian department. Congress either failed to respond to his reforms or rejected them. Calhoun's frustration with congressional inaction, political rivalries, and the ideological differences that dominated the late early republic spurred him to unilaterally create the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Calhoun expressed his nationalism in advising Monroe to approve the Missouri Compromise, which most other Southern politicians saw as a distinctly bad deal. Calhoun believed that continued agitation on the slavery issue threatened the Union, so he wanted the Missouri dispute to be concluded. As Secretary of State John Quincy Adams wrote in 1821, "Calhoun is a man of fair and candid mind, of honorable principles, of clear and quick understanding, of cool self-possession, of enlarged philosophical views, and of ardent patriotism. He is above all sectional and factious prejudices more than any other statesman of this Union with whom I have ever acted." [6] Historian Charles Wiltse agrees, noting, "Though he is known today primarily for his sectionalism, Calhoun was the last of the great political leaders of his time to take a sectional position-later than Daniel Webster, later than Henry Clay, later than Adams himself."[7] Calhoun originally was a candidate for President of the United States in the election of 1824. After failing to win the endorsement of the South Carolina legislature, he decided to go for the Vice Presidency. As no presidential candidate received a majority in the Electoral College, the election was ultimately resolved by the House of Representatives. Calhoun was elected Vice President in a landslide. Calhoun served four years under Adams, and then, in 1828, won re-election as Vice President running with Andrew Jackson. Calhoun believed that the outcome of the 1824 presidential election, in which the House made Adams President despite the greater popularity of Andrew Jackson, demonstrated that control of the federal government was subject to manipulation by Adams and Henry Clay. Calhoun resolved to thwart Adams' and Clay's nationalist program. He opposed it even as he held office with them. In 1828, Calhoun ran for reelection as the running mate of Andrew Jackson. He thus became one of two vice presidents to serve under two presidents (the other was George Clinton in the early 19th century). Under Andrew Jackson, Calhoun's Vice Presidency was also controversial. In time he developed a rift over policy with President Jackson, this time about hard cash, or policy which he considered to favor Northern financial interests. Calhoun opposed the Tariff of 1828 (also known as the Tariff of Abominations.) Calhoun had been assured that Jacksonians would reject the bill, but Northern Jacksonians were primarily responsible for its passage. Frustrated, Calhoun returned to his South Carolina plantation to write "South Carolina Exposition and Protest", an essay rejecting the nationalist philosophy he once advocated. He supported the theory of a concurrent majority through the doctrine of nullification—that individual states could override federal legislation they deemed unconstitutional. Nullification traced back to arguments by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in writing the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798. They had proposed that states could nullify the Alien and Sedition Acts. Jackson, who supported states' rights but believed that nullification threatened the Union, opposed it. Calhoun differed from Jefferson and Madison in explicitly arguing for a state's right to secede from the Union, if necessary, instead of simply nullifying certain federal legislation. James Madison rebuked supporters of nullification, stating that no state had the right to nullify federal law.[8] At the 1830 Jefferson Day dinner at Jesse Brown's Indian Queen Hotel, Jackson proposed a toast and proclaimed, "Our federal Union, it must be preserved." Calhoun replied, "the Union, next to our liberty, the most dear."[9] In May 1830, Jackson discovered that Calhoun had asked President Monroe to censure then-General Jackson for his invasion of Spanish Florida in 1818. Calhoun was then serving as James Monroe's Secretary of War (1817–1823). Jackson had invaded Florida during the Seminole War without explicit public authorization from Calhoun or Monroe. Calhoun's and Jackson's relationship deteriorated further. Calhoun defended his 1818 position. The feud between him and Jackson heated up as Calhoun informed the President that he risked another attack from his opponents. They started an argumentative correspondence, fueled by Jackson's opponents, until Jackson stopped the letters in July 1830. By February 1831, the break between Calhoun and Jackson was final. Responding to inaccurate press reports about the feud, Calhoun had published the letters in the United States Telegraph.[10] More damage was done when conservative Floride Calhoun organized Cabinet wives against Peggy Eaton, wife of 13th Secretary of War John Eaton. They alleged that John and Peggy Eaton had engaged in an adulterous affair while Mrs. Eaton was still legally married to her first husband John B. Timberlake. Some critics believed that the affair had contributed to Timberlake's suicide in 1828. The scandal, which became known as the Petticoat affair or the Peggy Eaton affair, resulted in the resignation of all Jackson's Cabinet except for Postmaster General William T. Barry and Secretary of State Martin Van Buren. Van Buren resigned as Secretary of State but only to take a position as United States Ambassador to Britain (1831–1832). In 1832, the states' rights theory was put to the test in the Nullification Crisis, after South Carolina passed an ordinance that nullified federal tariffs. The tariffs favored Northern manufacturing interests over Southern agricultural concerns. The South Carolina legislature declared them unconstitutional. Calhoun had formed a political party in South Carolina explicitly known as the Nullifier Party. In response to the South Carolina move, Congress passed the Force Bill, which empowered the President to use military power to force states to obey all federal laws. Jackson sent US Navy warships to Charleston harbor. South Carolina then nullified the Force Bill. Tensions cooled after both sides agreed to the Compromise Tariff of 1833, a proposal by Senator Henry Clay to change the tariff law in a manner which satisfied Calhoun, who by then was in the Senate.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

Remarks of Mr. Calhoun of South Carolina on the bill to prevent the interference of certain federal officers in elections: delivered in the Senate of the United States February 22, 1839

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

This book was converted from its physical edition to the digital format by a community of volunteers. You may find it for free on the web. Purchase of the Kindle edition includes wireless delivery.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

Remarks of Mr. Calhoun of South Carolina on the bill to prevent the interference of certain federal officers in elections: delivered in the Senate of the United States February 22, 1839

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

This book was converted from its physical edition to the digital format by a community of volunteers. You may find it for free on the web. Purchase of the Kindle edition includes wireless delivery.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Calhoun John Caldwell try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Calhoun John Caldwell try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!