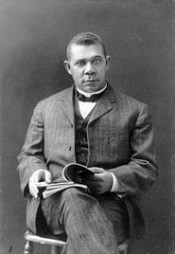

Chesnutt Charles Waddell

History · Antiquity · Aztec · Ancient Greece · Rome · Medieval Europe · Thrall · Kholop · Serfdom · Spanish New World colonies The Bible · Judaism · Christianity · Islam Africa · Atlantic · Arab · Coastwise · Angola · Britain and Ireland · British Virgin Islands · Brazil · Canada · India · Iran · Japan · Libya · Mauritania · Romania · Sudan · Swedish · United States Modern Africa · Debt bondage · Penal labour · Sexual slavery · Unfree labour Timeline · Abolitionism · Compensated emancipation · Opponents of slavery · Slave rebellion · Slave narrative Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856 – November 14, 1915) was an African American educator, orator, author and a dominant leader of the nation's African-American community from the 1890s to his death. Born into slavery "near a cross-roads post-office called Hale's Ford" in Franklin County, Virginia[1] and freed by the Civil War in 1865, he became the first leader of the new Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, then a normal teachers' college for blacks. Washington firmly believed in the Hampton system of industrial education: teaching trades like brick-making alongside book learning. Tuskegee was to become his area of operations and he literally helped build it from the ground up.[2] As a young man, he invented the surname Washington when all the other school children were giving their full names.[3] His "Atlanta Exposition" speech of 1895 appealed to middle class whites across the South, asking them to give blacks a chance to work and develop separately, while implicitly promising not to demand the vote. White leaders across the North, from politicians to industrialists, from philanthropists to churchmen, enthusiastically supported Washington, as did most middle class blacks. Meanwhile a more militant northern group, led by W. E. B. Du Bois rejected Washington's self-help philosophy and demanded recourse to politics, referring to the speech dismissively as "The Atlanta Compromise". The critics were marginalized until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, at which point more radical black leaders rejected Washington's philosophy and demanded federal civil rights laws. Washington was born into slavery to Jane, an enslaved African American woman on the Burroughs Plantation in southwest Virginia. He knew little about his white father. His family gained freedom in 1865 as the Civil War ended. After working in salt furnaces and coal mines in West Virginia for several years, Washington made his way east to Hampton Institute, established to educate freedmen. There, he worked his way through his studies and later attended Wayland Seminary to complete preparation as an instructor. In 1881, Hampton president Samuel C. Armstrong recommended Washington to become the first leader of Tuskegee Institute, the new normal school (teachers' college) in Alabama. He headed what became Tuskegee University for the rest of his life. Washington was the dominant figure in the African-American community in the United States from 1890 to 1915, especially after he achieved prominence for his "Atlanta Address of 1895". To many politicians and the public in general, he was seen as a popular spokesman for African-American citizens. Representing the last generation of black leaders born into slavery, Washington was generally perceived as a credible proponent of education for freedmen in the post-Reconstruction, Jim Crow South. Throughout the final 20 years of his life, he maintained his standing through a nationwide network of supporters, including black educators, ministers, editors, and businessmen, especially those who were liberal-leaning on social and educational issues. Critics called his network of supporters the "Tuskegee Machine". He gained access to top national leaders in politics, philanthropy and education, and was awarded honorary degrees from leading American universities. Late in his career, Washington was criticized by leaders of the NAACP, which was formed in 1909. W. E. B. Du Bois suggested activism to achieve civil rights. He labeled Washington "the Great Accommodator". Washington's response was that confrontation could lead to disaster for the outnumbered blacks. He believed that cooperation with supportive whites was the only way in the long run to overcome racism. Washington contributed secretly and substantially to legal challenges of segregation and disfranchisement of blacks.[4] In his public role, he believed he could achieve more by skillful accommodation to the social realities of the age of segregation.[5] Washington's work on education issues helped him enlist both the moral and substantial financial support of many major white philanthropists. He became friends with such self-made men as Standard Oil magnate Henry Huttleston Rogers; Sears, Roebuck and Company President Julius Rosenwald; and George Eastman, inventor and founder of Kodak. These individuals and many other wealthy men and women funded his causes, including Hampton and Tuskegee institutes. The schools were founded to produce teachers. However, graduates had often gone back to their local communities only to find precious few schools and educational resources to work with in the largely impoverished South. To address those needs, Washington enlisted his philanthropic network in matching funds programs to stimulate construction of numerous rural public schools for black children in the South. Together, these efforts eventually established and operated over 5,000 schools and supporting resources for the betterment of blacks throughout the South in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The local schools were a source of communal pride and were priceless to African-American families when poverty and segregation limited severely the life chances of the pupils. A major part of Washington's legacy, the number of model rural schools increased with matching funds from the Rosenwald Fund into the 1930s.[6] His autobiography, Up From Slavery, first published in 1901, is still widely read today. Booker T. Washington was born on April 5, 1856, on the Burrough's farm at the community of Hale's Ford, Virginia about 25 miles from Roanoke. His mother Jane was an enslaved black woman who worked as a cook and his father was an unknown white plantation owner. Jane was the slave of James Burroughs, a small farmer in Virginia.[7] Washington recalled Emancipation in early 1865: [Up from Slavery 19-21] As the great day drew nearer, there was more singing in the slave quarters than usual. It was bolder, had more ring, and lasted later into the night. Most of the verses of the plantation songs had some reference to freedom.... Some man who seemed to be a stranger (a United States officer, I presume) made a little speech and then read a rather long paper -- the Emancipation Proclamation, I think. After the reading we were told that we were all free, and could go when and where we pleased. My mother, who was standing by my side, leaned over and kissed her children, while tears of joy ran down her cheeks. She explained to us what it all meant, that this was the day for which she had been so long praying, but fearing that she would never live to see. In the summer of 1865, when he was nine, he migrated with his brother John and his sister Amanda to Malden in Kanawha County, West Virginia to join his stepfather, Washington Ferguson. Washington's mother was a major influence on his schooling. Even though she couldn't read herself, she bought her son spelling books which encouraged him to read. She then enrolled him in an elementary school, where Booker took the last name of Washington because he found out that other children had more than one name. When the teacher called on him and asked for his name he answered, "'Booker Washington,' as if I had been called by that name all my life;..." He worked with his mother and other free blacks as a salt-packer and in a coal mine. He even signed up briefly as a hired hand on a steamboat. About the only other jobs available for blacks at the time were in agriculture. He was hired as a houseboy for Viola Ruffner (née Knapp), the wife of General Lewis Ruffner, who owned the salt-furnace and coal mine. Many other houseboys had failed to satisfy the demanding Mrs. Ruffner, but Booker's diligence met her standards. Encouraged by Mrs. Ruffner, young Booker attended school and learned to read and to write. Soon he sought more education than was available in his community.[8] Leaving Malden at sixteen, Washington enrolled at the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, in Hampton, Virginia. Students with little income such as Washington could work at the school to pay their way. The normal school at Hampton was founded to train teachers, as education was seen as a critical need by the black community. Funding came from the federal government and white Protestant groups. From 1878 to 1879 Washington attended Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C., and returned to teach at Hampton. The president of Hampton, Samuel C. Armstrong recommended Washington to become the first principal at Tuskegee Institute, a similar school being founded in Alabama.[8] The organizers of the new all-black Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute found the energetic leader they sought in 25 year-old Booker T. Washington. Washington believed with a little self help, people may go from poverty to success. The new school opened on July 4, 1881, initially using space in a local church. The next year, Washington purchased a former plantation, which became the permanent site of the campus. Under his direction, his students literally built their own school: constructing classrooms, barns and outbuildings; growing their own crops and raising livestock, and providing for most of their own basic necessities.[9] Both men and women had to learn trades as well as academics. Washington helped raise funds to establish and operate hundreds of small community schools and institutions of higher educations for blacks.[10] The Tuskegee faculty utilized each of these activities to teach the students basic skills to take back to the mostly rural black communities throughout the South. The main goal was not to produce farmers and tradesmen, but teachers of farming and trades who taught in the new high schools and colleges for blacks across the South. The school later grew to become the present-day Tuskegee University.[11]

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

The Wife of his Youth and Other Stories of the Color Line, and Selected Essays

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Charles Waddell Chesnutt (1858-1932)-African-American educator, lawyer, and activist-was the most prominent black prose author of his day. The Wife of His Youth (1899) was Chesnutt's second collection of short stories, drawing upon his mixed race heritage.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

The Wife of his Youth and Other Stories of the Color Line, and Selected Essays

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Charles Waddell Chesnutt (1858-1932)-African-American educator, lawyer, and activist-was the most prominent black prose author of his day. The Wife of His Youth (1899) was Chesnutt's second collection of short stories, drawing upon his mixed race heritage.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Frederick Douglass

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

1.5/5

A 1899 biographical study by Charles Waddell Chesnutt, one of the most ambitious and influential African American writers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. An author and political activist, he is best known for his novels and short stories exploring complex issues of racial and social identity. Today he is considered to have been an innovator of American fiction and an important contributor to de-romanticizing trends in post-Civil War Southern literature. This book commemorates an American abolitionist, women's suffragist, editor, orator, author, statesman, minister and reformer, Frederick Douglass. The author describes this "self-made man" as a brilliant orator and intellectual. He narrates of his life beginning with his birth in slavery, tells about Douglass’ escape to New York disguised as a sailor, his career as a lecturer on the antislavery circuit and his relationship with William Lloyd Garrison, his political activism, work for African American civil liberties and so on.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Conjure Woman

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

1/5

A Conjure Woman is a collection of stories that belong to the pen of an outstanding writer Charles Chestnutt. The stories were written from the words of a former slave to a married couple who left their home place and came to the South. All stories are based on the true events that occurred in the life of the former slave. The book was written at the beginning of the twentieth century and was intended mainly for the white audience. It makes its readers think about the question of slavery and those times.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Colonel's Dream

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2/5

A 1905 novel by Charles Waddell Chesnutt (1858 –1932), an African American lawyer, author, essayist and political activist, best known for his novels and short stories exploring complex issues of racial and social identity. The book focuses on racial problems in the postwar South and tested out a number of possible social, economic, and political solutions. This prolific labour of Chesnutt became his final race novel, where he depicts a white idealist who confronts the racial hatred in the South.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Chesnutt Charles Waddell try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Chesnutt Charles Waddell try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!