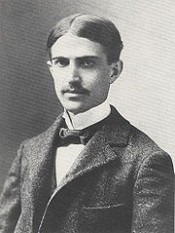

Crane Stephen

Stephen Crane (November 1, 1871 – June 5, 1900) was an American novelist, short story writer, poet and journalist. Prolific throughout his short life, he wrote notable works in the Realist tradition as well as early examples of American Naturalism and Impressionism. He is recognized by modern critics as one of the most innovative writers of his generation. The eighth surviving child of highly devout parents, Crane was raised in several New Jersey towns and Port Jervis, New York. He began writing at the age of 4 and had published several articles by the age of 16. Having little interest in university studies, he left school in 1891 and began work as a reporter and writer. Crane's first novel was the 1893 Bowery tale Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, which critics generally consider the first work of American literary Naturalism. He won international acclaim for his 1895 Civil War novel The Red Badge of Courage, which he wrote without any battle experience. In 1896, Crane endured a highly publicized scandal after acting as a witness for a suspected prostitute. Late that year he accepted an offer to cover the Spanish-American War as a war correspondent. As he waited in Jacksonville, Florida for passage to Cuba, he met Cora Taylor, the madam of a brothel with whom he would have a lasting relationship. While en route to Cuba, Crane's ship sank off the coast of Florida, leaving him marooned for several days in a small dinghy. His ordeal was later described in his well-known short story, "The Open Boat". During the final years of his life, he covered conflicts in Greece and Cuba, and lived in England with Cora, where he befriended writers such as Joseph Conrad and H. G. Wells. Plagued by financial difficulties and ill health, Crane died of tuberculosis in a Black Forest sanatorium at the age of 28. At the time of his death, Crane had become an important figure in American literature. He was nearly forgotten, however, until two decades later when critics revived interest in his life and work. Stylistically, Crane's writing is characterized by descriptive vividness and intensity, as well as distinctive dialects and irony. Common themes involve fear, spiritual crisis and social isolation. Although recognized primarily for The Red Badge of Courage, which has become an American classic, Crane is also known for his unconventional poetry and heralded for short stories such as "The Open Boat", "The Blue Hotel", "The Monster" and "The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky". His writing made a deep impression on 20th century writers, most prominent among them Ernest Hemingway, and is thought to have inspired the Modernists and the Imagists. Stephen Crane was born November 1, 1871, in Newark, New Jersey, to Reverend Jonathan Townley Crane, a minister in the Methodist Episcopal church, and Mary Helen Peck Crane, a clergyman's daughter.[1] He was the fourteenth and last child born to the couple; the 45 year old Helen Crane had lost her four previous children, who each died within one year of birth.[2] Nicknamed "Stevie" by the family, he joined eight surviving brothers and sisters—Mary Helen, George Peck, Jonathan Townley, William Howe, Agnes Elizabeth, Edmund Byran, Wilbur Fiske, and Luther.[3] Family legend maintains that Crane was descended from and named for a founder of Elizabethtown, New Jersey, who had come from England or Wales as early as 1665,[4] and a Revolutionary War patriot Stephen Crane (1709-1780) who served two terms as a delegate from New Jersey to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia.[5] Crane would later write that his father, Dr. Crane, "was a great, fine, simple mind" who had written numerous tracts on theology.[6] Although his mother was a popular spokeswoman for the Woman's Christian Temperance Union and a highly religious woman, Crane did not believe that "she was as narrow as most of her friends or family."[7] The young Stephen was raised primarily by his sister Agnes, who was 15 years his senior.[5] In 1876, the family moved to Port Jervis, New York, where Dr. Crane became the pastor of Drew Methodist Church, a position that he retained until his death.[5] As a child, Stephen was often sickly and afflicted by constant colds.[8] When the boy was almost two, his father wrote in his diary that his youngest son became "so sick that we are anxious about him." Despite his fragile nature, Crane was a precocious child who taught himself to read before the age of four.[3] His first known inquiry, recorded by his father, dealt with writing; at the age of three, while imitating his brother Townley's writing, he asked his mother, "how do you spell O?"[9] In December 1879, Crane wrote a poem about wanting a dog for Christmas. Entitled "I'd Rather Have –", it is his first surviving poem.[10] Stephen was not regularly enrolled in school until January 1880,[11] but he had no difficulty in completing two grades in six weeks. Recalling this feat, he wrote that it "sounds like the lie of a fond mother at a teaparty, but I do remember that I got ahead very fast and that father was very pleased with me."[12] Dr. Crane died on February 16, 1880, at the age of 60; Stephen was eight years old. Some 1,400 people mourned Dr. Crane at his funeral, more than double the size of his congregation.[13] After her husband's death, Mrs. Crane moved to Roseville, near Newark. She left Stephen in the care of his brother Edmund, with whom the young boy lived with cousins in Sussex County. He then lived with his brother William in Port Jervis for several years, until he and his sister Helen moved to Asbury Park to be with their brother Townley and his wife. Townley was a professional journalist; he headed the Long Branch department of both the New York Tribune and the Associated Press and also served as editor of the Asbury Park Shore Press. Agnes took a position at Asbury Park's intermediate school and moved in with Helen to care for the young Stephen.[14] Within a couple of years, several more losses struck the Crane family. First, Townley's wife, Fannie, died of Bright's disease in 1883 after the deaths of the couple's two young children. Agnes then became ill and died on June 10, 1884, of cerebrospinal meningitis at the age of 28.[15] Crane wrote his first known story, "Uncle Jake and the Bell Handle", when he was 14.[16] In the fall of 1885, he enrolled at Pennington Seminary, a ministry-focused coeducational boarding school 7 miles (11 km) north of Trenton,[17] where his father had been principal from 1849 to 1858.[5] Soon after her youngest son left for school, Mrs. Crane began suffering what the Asbury Park Shore Press reported as "a temporary aberration of the mind."[18] She had apparently recovered by early 1886, but later that year a fourth death in six years occurred in Stephen's immediate family when the twenty-three year old Luther died after falling in front of an oncoming train while working as a flagman for the Erie Railroad.[19] After two years, Crane left Pennington for Claverack College, a quasi-military school. He would later look back on his time at Claverack as "the happiest period of my life although I was not aware of it."[20] A classmate remembered him as a highly literate but erratic student, lucky to pass examinations in math and science, and yet "far in advance of his fellow students in his knowledge of History and Literature", his favorite subjects.[21] Not having a middle name like the other students, he took to signing his name "Stephen T. Crane" in order "to win recognition as a regular fellow".[21] Crane was seen as friendly, but also moody and rebellious. He sometimes skipped class in order to play baseball, a game in which he starred as catcher,[22] although he was also greatly interested in the school's military training program. He rose rapidly in the ranks of the student battalion.[23] One classmate described him as "indeed physically attractive without being handsome," but he was aloof, reserved and not generally popular at Claverack.[24] In the summer of 1888, Crane became his brother Townley's assistant at a New Jersey shore news bureau, working there every summer until 1892.[25] Crane's first signed publication was an article on the explorer Henry M. Stanley's famous quest to find the English missionary David Livingstone in Africa. It appeared in the February 1890 Claverack College Vidette.[26] Within a few months, however, Crane was persuaded by his family to forgo a military career and transfer to Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania, in order to pursue a mining engineering degree.[27] He registered at Lafayette on September 12 and promptly became involved in extracurricular activities; he took up baseball once more and joined the largest fraternity, Delta Upsilon, and two rival groups: the Washington Literary Society and the Franklin Literary Society.[28] Crane infrequently attended classes and ended the semester with grades for four of the seven courses he had taken.[29] After only one semester, Crane transferred to Syracuse University where he enrolled as a non-degree candidate in the College of Liberal Arts.[30] He roomed in the Delta Upsilon fraternity house and joined the baseball team. Attending merely one class (English Literature) during the middle trimester, he remained in residence while taking no courses in the third trimester.[31] Putting more emphasis on his writing, Crane began to experiment with tone and style while trying out different subjects.[32] A fictional story of his called "Great Bugs of Onondaga" ran simultaneously in the Syracuse Daily Standard and the New York Tribune.[33] Declaring college "a waste of time", Crane decided to become a full-time writer and reporter. He attended a Delta Upsilon chapter meeting on June 12, 1891, but shortly afterwards left college for good.[34] In the summer of 1891, Crane showed two of his stories to Tribune editor Willis Fletcher Johnson, a friend of the Crane family, who accepted them for the publication. "Hunting Wild Dogs" and "The Last of the Mohicans" were the first of fourteen unsigned Sullivan County sketches and tales that would appear in the Tribune between February and July 1892. Crane also showed Johnson an early draft of his first novel, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets.[35] Later that summer, Crane met and befriended author Hamlin Garland, who had been lecturing locally on American literature and the expressive arts; on August 17 he gave a talk on novelist William Dean Howells, which Crane wrote up for the Tribune.[36] Garland became a mentor for and champion of the young writer, whose intellectual honesty impressed him. Their relationship suffered in later years, however, because Garland disapproved of Crane's alleged immorality.[37]

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

The Little RegimentAnd Other Episodes of the American Civil War

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

War is Kind

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

This is an electronic edition of the complete book complemented by author biography and illustrations.-The book was designed for optimal navigation on the Kindle, PDA, Smartphone, and other electronic readers. It is formatted to display on all electronic devices including the Kindle, Smartphones and other Mobile Devices with a small display. ************ The Black Riders and Other Lines and War is Kind, was unconventional for the time in that it was written in free verse without rhyme, meter, or even titles for individual works. They are typically short in length and although several poems, such as "Do not weep, maiden, for war is kind", use stanzas and refrains, most do not. Crane also differed from his peers and poets of later generations in that his work contains allegory, dialectic and narrative situations. - Excerpted from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. More e-Books from MobileReference - Best Books. Best Price. Best Search and Navigation (TM) All fiction books are only $0.99. All collections are only $5.99Designed for optimal navigation on Kindle and other electronic devices Search for any title: enter mobi (shortened MobileReference) and a keyword; for example: mobi ShakespeareTo view all books, click on the MobileReference link next to a book title Literary Classics: Over 10,000 complete works by Shakespeare, Jane Austen, Mark Twain, Conan Doyle, Jules Verne, Dickens, Tolstoy, and other authors. All books feature hyperlinked table of contents, footnotes, and author biography. Books are also available as collections, organized by an author. Collections simplify book access through categorical, alphabetical, and chronological indexes. They offer lower price, convenience of one-time download, and reduce clutter of titles in your digital library. Religion: The Illustrated King James Bible, American Standard Bible, World English Bible (Modern Translation), Mormon Church's Sacred Texts Philosophy: Rousseau, Spinoza, Plato, Aristotle, Marx, Engels Travel Guides and Phrasebooks for All Major Cities: New York, Paris, London, Rome, Venice, Prague, Beijing, Greece Medical Study Guides: Anatomy and Physiology, Pharmacology, Abbreviations and Terminology, Human Nervous System, Biochemistry College Study Guides: FREE Weight and Measures, Physics, Math, Chemistry, Organic Chemistry, Statistics, Languages, Philosophy, Psychology, Mythology History: Art History, American Presidents, U.S. History, Encyclopedias of Roman Empire, Ancient Egypt Health: Acupressure Guide, First Aid Guide, Art of Love, Cookbook, Cocktails, Astrology Reference: The World's Biggest Mobile Encyclopedia; CIA World Factbook, Illustrated Encyclopedias of Birds, Mammals --This text refers to the Kindle Edition edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

The Little RegimentAnd Other Episodes of the American Civil War

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

War is Kind

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

This is an electronic edition of the complete book complemented by author biography and illustrations.-The book was designed for optimal navigation on the Kindle, PDA, Smartphone, and other electronic readers. It is formatted to display on all electronic devices including the Kindle, Smartphones and other Mobile Devices with a small display. ************ The Black Riders and Other Lines and War is Kind, was unconventional for the time in that it was written in free verse without rhyme, meter, or even titles for individual works. They are typically short in length and although several poems, such as "Do not weep, maiden, for war is kind", use stanzas and refrains, most do not. Crane also differed from his peers and poets of later generations in that his work contains allegory, dialectic and narrative situations. - Excerpted from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. More e-Books from MobileReference - Best Books. Best Price. Best Search and Navigation (TM) All fiction books are only $0.99. All collections are only $5.99Designed for optimal navigation on Kindle and other electronic devices Search for any title: enter mobi (shortened MobileReference) and a keyword; for example: mobi ShakespeareTo view all books, click on the MobileReference link next to a book title Literary Classics: Over 10,000 complete works by Shakespeare, Jane Austen, Mark Twain, Conan Doyle, Jules Verne, Dickens, Tolstoy, and other authors. All books feature hyperlinked table of contents, footnotes, and author biography. Books are also available as collections, organized by an author. Collections simplify book access through categorical, alphabetical, and chronological indexes. They offer lower price, convenience of one-time download, and reduce clutter of titles in your digital library. Religion: The Illustrated King James Bible, American Standard Bible, World English Bible (Modern Translation), Mormon Church's Sacred Texts Philosophy: Rousseau, Spinoza, Plato, Aristotle, Marx, Engels Travel Guides and Phrasebooks for All Major Cities: New York, Paris, London, Rome, Venice, Prague, Beijing, Greece Medical Study Guides: Anatomy and Physiology, Pharmacology, Abbreviations and Terminology, Human Nervous System, Biochemistry College Study Guides: FREE Weight and Measures, Physics, Math, Chemistry, Organic Chemistry, Statistics, Languages, Philosophy, Psychology, Mythology History: Art History, American Presidents, U.S. History, Encyclopedias of Roman Empire, Ancient Egypt Health: Acupressure Guide, First Aid Guide, Art of Love, Cookbook, Cocktails, Astrology Reference: The World's Biggest Mobile Encyclopedia; CIA World Factbook, Illustrated Encyclopedias of Birds, Mammals --This text refers to the Kindle Edition edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Third Violet

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Purchase of this book includes free trial access to www.million-books.com where you can read more than a million books for free. This is an OCR edition with typos. Excerpt from book: CHAPTER IV One day Hollander! said : ' There are forty- two people at Hemlock Inn, I think. Fifteen are middle-aged ladies of the most aggressive respectability. They have come here for no discernible purpose save to get where they can see people and be displeased at them. They sit in a large group on that porch, and take measurements of character as importantly as if they constituted the jury of heaven. When I arrived at Hemlock Inn, I at once cast my eye search- ingly about me. Perceiving this assemblage, I cried, " There they are!" Barely waiting to change my clothes, I made for this formidable body and endeavoured to conciliate it. Almost every day I sit down among them and lie like a machine. Privately Ibelieve they should be hanged, but publicly I glisten with admiration. Do you know, there is one of 'em who I know has not moved from the inn in eight days, and this morning I said to her, " These long walks in the clear mountain air are doing you a world of good." And I keep continually saying, "Your frankness is so charming!" Because of the great law of universal balance, I know that this illustrious corps will believe good of themselves with exactly the same readiness that they will believe ill of others. So I ply them with it. In consequence, the worst they ever say of me is, " Isn't that Mr. Hollanden a peculiar man ?" And you know, my boy, that's not so bad for a literary person.' After some thought he added: ' Good people, too. Good wives, good mothers, and everything of that kind, you know. But conservative, very conservative. Hate anything radical. Cannot endure it. Were that way themselves once, you know. They hit the mark, too, sometimes. Such general volleyings can't fail to hit everything. May the devil fly away with them!' Hawker regarded the group nervo...

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Men, Women, and Boats

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Edited with an Introduction by Vincent Starrett --This text refers to an alternate Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

- Literature & Fiction / Literary

- Literature & Fiction / Authors, A-Z / (S) / Swinburne, Algernon Charles

- Religion & Spirituality / Christianity / Literature & Fiction / Fiction

- Romance

- Literature & Fiction / Authors, A-Z / (D) / Dickens, Charles / Paperback

- Books / Confederate States of America / Army

- Books / Didactic fiction

- Books / Australia

- Nonfiction / Education / Education Theory / History

- Literature & Fiction / Short Stories / General

if you like Crane Stephen try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

- Literature & Fiction / Literary

- Literature & Fiction / Authors, A-Z / (S) / Swinburne, Algernon Charles

- Religion & Spirituality / Christianity / Literature & Fiction / Fiction

- Romance

- Literature & Fiction / Authors, A-Z / (D) / Dickens, Charles / Paperback

- Books / Confederate States of America / Army

- Books / Didactic fiction

- Books / Australia

- Nonfiction / Education / Education Theory / History

- Literature & Fiction / Short Stories / General

if you like Crane Stephen try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!