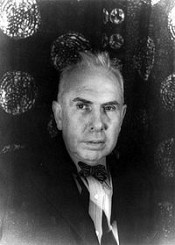

Dreiser Theodore

Theodore Herman Albert Dreiser (August 27, 1871 – December 28, 1945) was an American novelist and journalist. He pioneered the naturalist school and is known for portraying characters whose value lies not in their moral code, but in their persistence against all obstacles, and literary situations that more closely resemble studies of nature than tales of choice and agency.[1] Dreiser was born in Terre Haute, Indiana, to Sarah and John Paul Dreiser, a strict Catholic . John Paul Dresser was a German immigrant and Sarah was from the Mennonite farming community near Dayton, Ohio; she was disowned for marrying John and converting to Roman Catholicism. Theodore was the twelfth of thirteen children (the ninth of the ten surviving). The popular songwriter Paul Dresser (1859–1906) was his older brother. From 1889 – 1890, Theodore attended Indiana University before flunking out . Within several years, he was writing for the Chicago Globe newspaper and then the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. He wrote several articles on writers like Nathaniel Hawthorne, William Dean Howells, Israel Zangwill and John Burroughs, and interviewed public figures like Andrew Carnegie, Marshall Field, Thomas Edison and Theodore Thomas[2]. Other interviewees included Lillian Nordica, Emilia E. Barr, Philip Armour and Alfred Stieglitz[3]. After proposing in 1893, he married Sara White on December 28, 1898. They ultimately separated in 1909, partly as a result of Dreiser's infatuation with Thelma Cudlipp, the teenage daughter of a work colleague, but were never formally divorced.[4] His first novel, Sister Carrie (1900), tells the story of a woman who flees her country life for the city (Chicago) and falls into a wayward life. It sold poorly, but it later acquired a considerable reputation. (It was made into a 1952 film by William Wyler, which starred Laurence Olivier and Jennifer Jones.) He was a witness to a lynching in 1893, and wrote the short story "Nigger Jeff", which appeared in Ainslee's Magazine, in 1901.[5] His second novel, Jennie Gerhardt, was published in 1911. Many of Dreiser's subsequent novels dealt with social inequality. His first commercial success was An American Tragedy (1925), which was made into a film in 1931 and again in 1951. In 1892, when Dreiser began work as a newspaperman he "began to observe a certain type of crime in the United States that proved very common. It seemed to spring from the fact that almost every young person was possessed of an ingrown ambition to be somebody financially and socially." "Fortune hunting became a disease" with the frequent result of a peculiarly American kind of crime "many forms of murder for money...the young ambitious lover of some poorer girl...(for) a more attractive girl with money or position...it was not always possible to drop the first girl. What usually stood in the way was pregnancy."[6] Dreiser claimed to have collected such stories every year between 1895 and 1935. The murder in 1911 of Avis Linnell by Clarence Richeson particularly caught his attention. By 1919 this murder was the basis of one of two separate novels begun by Dreiser. The 1906 murder of Grace Brown by Chester Gillette eventually became the basis for An American Tragedy.[7] Though primarily known as a novelist, Dreiser published his first collection of short stories, Free and Other Stories in 1918. The collection contained 11 stories. A particularly interesting story, "My Brother Paul", was a brief biography of his older brother, Paul Dresser, who was a famous songwriter in the 1890s. This story was the basis for the 1942 romantic movie, "My Gal Sal". Other works include The "Genius" and Trilogy of Desire (a three-parter based on the remarkable life of the Chicago streetcar tycoon Charles Tyson Yerkes and composed of The Financier (1912), The Titan (1914), and The Stoic). The latter was published posthumously in 1947. Because of his depiction of then unaccepted aspects of life, such as sexual promiscuity in The "Genius", Dreiser was often forced to battle against censorship. Politically, Dreiser was involved in several campaigns against social injustice. This included the lynching of Frank Little, one of the leaders of the Industrial Workers of the World, the Sacco and Vanzetti case, the deportation of Emma Goldman, and the conviction of the trade union leader Tom Mooney. In November 1931 Dreiser led the National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners to the coalfields of southeastern Kentucky, where they took testimony from coal miners in Pineville and Harlan on the violence against the miners and their unions by the coal operators.[8] Dreiser was a committed socialist, and wrote several non-fiction books on political issues. These included Dreiser Looks at Russia (1928), the result of his 1927 trip to the Soviet Union, and two books presenting a critical perspective on capitalist America, Tragic America (1931) and America Is Worth Saving (1941). His vision of capitalism and a future world order with a strong American military dictate combined with the harsh criticism of the latter made him unpopular within the official circles. Although less politically radical friends, such as H.L. Mencken, spoke of Dreiser's relationship with communism as an "unimportant detail in his life," Dreiser's biographer Jerome Loving notes that his political activities since the early 1930s had "clearly been in concert with ostensible communist aims with regard to the working class." [9]. The author died on December 28, 1945 in Hollywood, aged 74. Dreiser had an enormous influence on the generation that followed his. In his tribute "Dreiser" from Horses and Men (1923), Sherwood Anderson writes: Alfred Kazin characterized Dreiser as "stronger than all the others of his time, and at the same time more poignant; greater than the world he has described, but as significant as the people in it," while Larzer Ziff (UC Berkeley) remarked that Dreiser "succeeded beyond any of his predecessors or successors in producing a great American business novel." Arguably, Dreiser succeeded beyond any of his predecessors or successors in producing the great American novel. Renowned mid-century literary critic Irving Howe spoke of Dreiser as "among the American giants, one of the very few American giants we have had."[10] A British view of Dreiser came from the publisher Rupert Hart-Davis: "Theodore Dreiser's books are enough to stop me in my tracks, never mind his letters — that slovenly turgid style describing endless business deals, with a seduction every hundred pages as light relief. If he's the great American novelist, give me the Marx Brothers every time."[11] One of Dreiser's strongest champions during his lifetime, H.L. Mencken, declared "that he is a great artist, and that no other American of his generation left so wide and handsome a mark upon the national letters. American writing, before and after his time, differed almost as much as biology before and after Darwin. He was a man of large originality, of profound feeling, and of unshakable courage. All of us who write are better off because he lived, worked, and hoped."[12] Dreiser's great theme, the tremendous tensions that can arise among ambition, desire, and social mores, seems even more relevant today than in his own time, and in particular his "Trilogy of Desire" resonates powerfully. Dreiser is very much an author for the twenty-first century, which can be said of only a tiny handful of the other novelists of his day.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

plays of the natural and the supernatural

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Purchase of this book includes free trial access to www.million-books.com where you can read more than a million books for free. This is an OCR edition with typos. Excerpt from book: LAUGHING GAS Scene The operating-room of the Michael Slade Hospital, a glistening chamber of white porcelain and white tile. Nickel operating table in the foreground. Racks of surgical implements and supplies to either side. A strong, even light from the north French windows. Attendants in white bustling about preparatory to an operation. Enter Fenway Bail, an eminent surgeon, and Jason James Vata- Beel, his friend, a celebrated physician. They are followed by Arthur Galley, chief house physician ; Slason Tufts, his assistant; Franklin Dryden, the anesthetist, and two nurses. BAIL I [A cool, sallow-faced, collected man of perhaps fifty- five, wise and incisive.] Well, Jason, here you are, a victim of surgery after all! VATABEEL [Tall, gaunt, all of fifty-eight, very distinguished, a little pale from recent suffering, a bandage about his neck, beginning, to loosen his shirt in front.] The last time I took ether I had a very strange experience or dream, one of the best of the etheric variety, I fancy. I am wondering whether it will repeat itself today. Bail [Examining a case of instruments, and busy with asides to Gailey and others.] I was thinking of using nitrous oxide, unless you would prefer ether. It seems to me a little too much for a minor operation. I doubt whether I shall be four or five minutes in all. Just as you say, however. VATABEEL [TFi£A a dry, medical smile.] Far be it from me to demand ether. I dislike the stuff intensely. [He begins to take-off his coat and waistcoat and adjusts an aseptic apron.] [To Gailey.] I shall want a retractor, clamps and thumb forceps. Are all the different ligatures here? Ah, yes,I see. (To Vatabeel) : Now, 'Doctor, if you will just make yourself comfortable. (He indicates t...

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

hey rub a dub dub a book of the mystery and wonder and terror of life

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

A collection of essays, playlets, character pieces, and other nonfiction oddments.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

free and other stories

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

1918. Contents: Free; McEwen of the Shining Slave Makers; Nigger Jeff; The Lost Phoebe; The Second Choice; A Story of Stories; Old Rogaum and His Theresa; Will You Walk Into My Parlor; The Cruise of the Idlewild; Married; When the Old Century Was New. --This text refers to the Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a hoosier holiday

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

A novel of the first-rate American writer of the 19th-20th centuries, Theodore Dreiser is an autobiographical work, written in 1916. The author writes about his road trip to Indiana with an artist Franklin Booth. He gives a detailed description, sometimes cynical and critical, of the automobile ride from his home city of New York to Warsaw, Sullivan, and other whistle stop town far removed; and upon arrival, becomes sentimental, about the landscape of his childhood land. An engaging observation of life and outskirts a pioneer of literary realism.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a book about myself

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

This volume is produced from digital images created through the University of Michigan University Library's preservation reformatting program. The Library seeks to preserve the intellectual content of items in a manner that facilitates and promotes a variety of uses. The digital reformatting process results in an electronic version of the text that can both be accessed online and used to create new print copies. This book and thousands of others can be found in the digital collections of the University of Michigan Library. The University Library also understands and values the utility of print, and makes reprints available through its Scholarly Publishing Office.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Sister Carrie: a Novel

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Theodor Dreiser published his novel-challenge in the 1900's. It is a story of 18-year-old girl who moves from her native country to Chicago and becomes there a woman maintained by a man as his mistress. This is because of that it becomes prohibited. The publisher was afraid to release the work as it was, so he changed something in it. After years the masterpiece by Dreiser can be read as it was planned originally.

The novel shows how acute, wise and accurate the author was in his views. He was perhaps the first to depict a woman - crafty, with the behavior beyond the moral norms, with the limited freedom of actions. For sanctimonious America of 19th century it was like ribaldry. Dreiser shows how dangerous for every human being hesitating in finding one's position in life, not deciding and not making own choice; and how dangerous waiting for the fate's sign and not doing anything by oneself. Such choices in the book leads it's characters to the end or to the glory, to the happiness or to the abyss. This masterpiece is full of detailed analysis of the heroes, deep immersion into their psychology. Being followed for the author through all this plot turns attentive reader will be rewarded by the author's talent to reflect the deep psychology of the images. Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The novel shows how acute, wise and accurate the author was in his views. He was perhaps the first to depict a woman - crafty, with the behavior beyond the moral norms, with the limited freedom of actions. For sanctimonious America of 19th century it was like ribaldry. Dreiser shows how dangerous for every human being hesitating in finding one's position in life, not deciding and not making own choice; and how dangerous waiting for the fate's sign and not doing anything by oneself. Such choices in the book leads it's characters to the end or to the glory, to the happiness or to the abyss. This masterpiece is full of detailed analysis of the heroes, deep immersion into their psychology. Being followed for the author through all this plot turns attentive reader will be rewarded by the author's talent to reflect the deep psychology of the images. Show more

The Financier, a novel

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

1.5/5

A brilliant in its historical authenticity novel by the foremost American literary naturalist, Theodore Herman Albert Dreiser. “The Financier” tells a story of American business elite, people who gathered enormous wealth during the second half of the nineteenth century. The novel begins with the early years of an American capitalist Frank Cowperwood and follows his life to the period when he, feeling the strength on the professional experience and capital, advances his vital slogan, concerning the first and foremost importance of his wishes. This is a novel of the world where only the strongest are able to “survive” – those who can hold out against the blows of fate and continue their way to their aim. It is also a timely story of speculation, corruption and impunity of thieves.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Dreiser Theodore try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Dreiser Theodore try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!