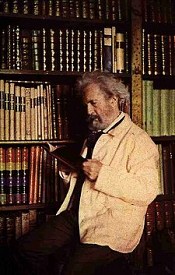

Flammarion Camille

Nicolas Camille Flammarion (26 February 1842—3 June 1925) was a French astronomer and author. He was a prolific author of more than fifty titles, including popular science works about astronomy, several notable early science fiction novels, and several works about Spiritualism and related topics. He also published the magazine L'Astronomie, starting in 1882. He maintained a private observatory at Juvisy-sur-Orge, France. Camille Flammarion was born in Montigny-le-Roi, Haute-Marne, France. He was the brother of Ernest Flammarion (1846-1936), founder of the Groupe Flammarion publishing house. He was a founder and the first president of the Société Astronomique de France, which originally had its own independent journal, BSAF (Bulletin de la Société astronomique de France), first published in 1887. In January, 1895, after 13 volumes of L'Astronomie and 8 of BSAF, the two merged, making L'Astronomie the Bulletin of the Societé. The 1895 volume of the combined journal was numbered 9, to preserve the BSAF volume numbering, but this had the consequence that volumes 9 to 13 of L'Astronomie can each refer to two different publications, five years apart of each other.[1] The enigmatic "Flammarion woodcut" first appeared in an 1888 Flammarion publication. In 1907 he wrote that he believed that dwellers on Mars had tried to communicate with the Earth in the past.[2] He also believed in 1907 that a seven tailed comet was heading toward Earth.[3] In 1910 for the appearance of Halley's Comet, he believed the gas from the comet's tail "would impregnate [the Earth's] atmosphere and possibly snuff out all life on the planet."[4] His second wife was Gabrielle Renaudot Flammarion, also a noted astronomer. He died in Juvisy-sur-Orge. Because of his scientific background, he approached spiritualism and reincarnation from the viewpoint of the scientific method, writing, "It is by the scientific method alone that we may make progress in the search for truth. Religious belief must not take the place of impartial analysis. We must be constantly on our guard against illusions."[5]. He was chosen to speak at the funerals of Allan Kardec, founder of Spiritism, on 2 April 1869, when he re-affirmed that "spiritism is not a religion but a science" His spiritualism studies also influenced some of his science fiction. In "Lumen", a human character meets the soul of an alien, able to cross the universe faster than light, that has been reincarnated on many different worlds, each with their own gallery of organisms and their evolutionary history. Other than that, his writing about other worlds adhered fairly closely to then current ideas in evolutionary theory and astronomy. He was the first to suggest the names Triton and Amalthea for moons of Neptune and Jupiter, respectively, although these names were not officially adopted until many decades later.[6] Named after him "What intelligent being, what being capable of responding emotionally to a beautiful sight, can look at the jagged, silvery lunar crescent trembling in the azure sky, even through the weakest of telescopes, and not be struck by it in an intensely pleasurable way, not feel cut off from everyday life here on earth and transported toward that first stop on the celestial journeys? What thoughtful soul could look at brilliant Jupiter with its four attendant satellites, or splendid Saturn encircled by its mysterious ring, or a double star glowing scarlet and sapphire in the infinity of night, and not be filled with a sense of wonder? Yes, indeed, if humankind — from humble farmers in the fields and toiling workers in the cities to teachers, people of independent means, those who have reached the pinnacle of fame or fortune, even the most frivolous of society women — if they knew what profound inner pleasure await those who gaze at the heavens, then France, nay, the whole of Europe, would be covered with telescopes instead of bayonets, thereby promoting universal happiness and peace." — Camille Flammarion, 1880 "This end of the world will occur without noise, without revolution, without cataclysm. Just as a tree loses leaves in the autumn wind, so the earth will see in succession the falling and perishing all its children, and in this eternal winter, which will envelop it from then on, she can no longer hope for either a new sun or a new spring. She will purge herself of the history of the worlds. The millions or billions of centuries that she had seen will be like a day. It will be only a detail completely insignificant in the whole of the universe. Presently the earth is only an invisible point among all the stars, because, at this distance, it is lost through its infinite smallness in the vicinity of the sun, which itself is by far only a small star. In the future, when the end of things will arrive on this earth, the event will then pass completely unperceived in the universe. The stars will continue to shine after the extinction of our sun, as they already shone before our existence. When there will no longer be on the the earth a sole concern to contemplate, the constellations will reign again in the noise as they reigned before the appearance of man on this tiny globule. There are stars whose light shone some millions of years before we arrived … The luminous rays that we receive actually then departed from their bosom before the time of the appearance of man on the earth. The universe is so immense that it appears immutable, and that the duration of a planet such as that of the earth is only a chapter, less than that, a phrase, less still, only a word of the universe’s history." — Camille Flammarion, Le Fin du Monde (The End of the World)

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

Mysterious Psychic ForcesAn Account of the Author's Investigations in PsychicalResearch,Together with Those of Other European Savants

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

the atmosphere

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Purchase of this book includes free trial access to www.million-books.com where you can read more than a million books for free. This is an OCR edition with typos. Excerpt from book: CHAPTER VII. SHOOTING-STARS.BOLIDES.AEROLITES.STONES FALLING FROM THE SKY. None of my readers will have failed to have been struck with surprise, during the calm of a fine starry night, by the spectacle of a star gliding noiselessly through the celestial vault to extinction. Some, perhaps, of those who peruse these pages, may have enjoyed the rare privilege of beholding, not only a shooting-star, but a more brilliant and sometimes very exciting phenomenon, viz. the rapid passage through space cf a flaming bolide, scattering a gleaming light in all directionsa globe of fire leaving a luminous track behind it, and sometimes bursting with an explosion like that of an enormous shell, and a report like that of a cannon. Some, perhaps, also, by a still more fortunate chance, have had an opportunity of picking up a fragment of an exploded bolidea piece that has fallen from the skyan aerolite or stone that has come down from the heights of the atmosphere. We here have three distinct facts, which nevertheless seem to be related to each other in their origin. The progress made during the last few years in the special study of these meteors is a reason for considering them separately, taking first the shooting-stars, then the bolides, and lastly the aerolites. The first point to consider in the study of shoot ing-stars is the measurement of the height at which they are seen. Two spectators, placed at a distance of some miles from each other, notice the passage of a shooting-star amongst the constellations ; its path is not exactly the same to both observers, owing to perspective. From the observation of these two paths the distance can be obtained. This method, as early as 1798, two German savans, Brandos and Benzemberg, had already made use of. From the latest researches u...

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

Mysterious Psychic ForcesAn Account of the Author's Investigations in PsychicalResearch,Together with Those of Other European Savants

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

the atmosphere

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Purchase of this book includes free trial access to www.million-books.com where you can read more than a million books for free. This is an OCR edition with typos. Excerpt from book: CHAPTER VII. SHOOTING-STARS.BOLIDES.AEROLITES.STONES FALLING FROM THE SKY. None of my readers will have failed to have been struck with surprise, during the calm of a fine starry night, by the spectacle of a star gliding noiselessly through the celestial vault to extinction. Some, perhaps, of those who peruse these pages, may have enjoyed the rare privilege of beholding, not only a shooting-star, but a more brilliant and sometimes very exciting phenomenon, viz. the rapid passage through space cf a flaming bolide, scattering a gleaming light in all directionsa globe of fire leaving a luminous track behind it, and sometimes bursting with an explosion like that of an enormous shell, and a report like that of a cannon. Some, perhaps, also, by a still more fortunate chance, have had an opportunity of picking up a fragment of an exploded bolidea piece that has fallen from the skyan aerolite or stone that has come down from the heights of the atmosphere. We here have three distinct facts, which nevertheless seem to be related to each other in their origin. The progress made during the last few years in the special study of these meteors is a reason for considering them separately, taking first the shooting-stars, then the bolides, and lastly the aerolites. The first point to consider in the study of shoot ing-stars is the measurement of the height at which they are seen. Two spectators, placed at a distance of some miles from each other, notice the passage of a shooting-star amongst the constellations ; its path is not exactly the same to both observers, owing to perspective. From the observation of these two paths the distance can be obtained. This method, as early as 1798, two German savans, Brandos and Benzemberg, had already made use of. From the latest researches u...

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

omega the last days of the world

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Nicolas Camille Flammarion, a French astronomer and author of popular science works about astronomy, several notable early science fiction novels, and several works about Spiritualism.

This work focuses on a peculiar suggestion, concerning the destruction of our platen as a result of a collision with a huge comet. According to the plot, the action will take place in the 25th century. Flammarion gives a vivid description of the consequences of that horrifying event that causes a series of physical, psychic, and social changes on Earth. A gripping story with interesting characters, in spite of its age.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

This work focuses on a peculiar suggestion, concerning the destruction of our platen as a result of a collision with a huge comet. According to the plot, the action will take place in the 25th century. Flammarion gives a vivid description of the consequences of that horrifying event that causes a series of physical, psychic, and social changes on Earth. A gripping story with interesting characters, in spite of its age.

Show more

linconnu the unknown

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Originally published in 1900. This volume from the Cornell University Library's print collections was scanned on an APT BookScan and converted to JPG 2000 format by Kirtas Technologies. All titles scanned cover to cover and pages may include marks notations and other marginalia present in the original volume.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

death and its mystery before death proofs of the existence of the soul

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Astronomy for Amateurs

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Many of the earliest books, particularly those dating back to the 1900s and before, are now extremely scarce and increasingly expensive. We are republishing these classic works in affordable, high quality, modern editions, using the original text and artwork. --This text refers to the Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Flammarion Camille try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Flammarion Camille try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!