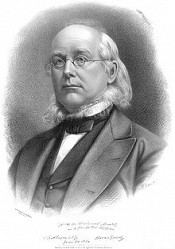

Greeley Horace

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American editor of a leading newspaper, a founder of the Liberal Republican Party, a reformer, and a politician. His New York Tribune was America's most influential newspaper from the 1840s to the 1870s and "established Greeley's reputation as the greatest editor of his day."[1] Greeley used it to promote the Whig and Republican parties, as well as opposition to slavery and a host of reforms. Crusading against the corruption of Ulysses S. Grant's Republican administration, he was the new Liberal Republican Party's candidate in the 1872 U.S. presidential election. Despite having the additional support of the Democratic Party, he lost in a landslide. He is currently the only presidential candidate who has died during the electoral process. Greeley was born on February 3, 1811,[2] in Amherst, New Hampshire, the son of poor farmers Zaccheus and Mary Greeley. He declined a scholarship to Phillips Exeter Academy and left school at the age of 14; he apprenticed as a printer in Poultney, Vermont, at The Northern Star, and moved to New York City in 1831. In 1834 he founded the weekly the New Yorker, which consisted mostly of clippings from other magazines. On July 5, 1836 Greeley married Mary Cheney Greeley, an intermittent suffragette, in Warrenton, North Carolina. Horace Greeley spent as little time as possible with his wife and would sleep in a boarding house when in New York City rather than be with her. Only two of their seven children survived into adulthood. In 1838 leading Whig politicians selected him to edit a major national campaign newspaper, the Jeffersonian, which reached 15,000 circulation. Whig leader William Seward found him "rather unmindful of social usages, yet singularly clear, original, and decided, in his political views and theories." In 1840 he edited a major campaign newspaper, the Log Cabin, which reached 90,000 subscribers nationwide, and helped elect William Henry Harrison president on the Whig ticket. In 1841 he merged his papers into the New York Tribune. It soon was a success as the leading Whig paper in the metropolis; its weekly edition reached tens of thousands of subscribers across the country. Greeley was editor of the Tribune for the rest of his life, using it as a platform for advocacy of all his causes. As historian Allan Nevins explains: Greeley prided himself in taking radical positions on all sorts of social issues; few readers followed his suggestions. Utopia fascinated him; influenced by Albert Brisbane he promoted Fourierism. His journal had Karl Marx (as well as Friedrich Engels) as European correspondent in the early 1850s (although most of his views sharply contrasted with the ones promoted by marxism).[2] He promoted all sorts of agrarian reforms, including homestead laws. He was elected as a Whig to the Thirtieth Congress to fill the vacancy caused by the unseating of David S. Jackson and served from December 4, 1848, to March 3, 1849. Greeley supported liberal policies towards settlers; in a July 13, 1865 editorial, he famously advised "Go West, young man, go West and grow up with the country." Some have claimed that the phrase was originally written by John Soule in the Terre Haute Express in 1851,[3] but it is most often attributed to Greeley. Historian Walter A. McDougall quotes Josiah Grinnell, the founder of Iowa's Grinnell College, as saying, "I was the young man to whom Greeley first said it, and I went." Researcher Fred R. Shapiro questions whether Greeley ever used the term at all and cites, instead, an occurrence of Greeley writing "If any young man is about to commence the world, we say to him, publicly and privately, Go to the West" in the Aug. 25, 1838, issue of the newspaper New Yorker.[4] A champion of the working man, he attacked monopolies of all sorts and rejected land grants to railroads. Industry would make everyone rich, he insisted, as he promoted high tariffs. He supported vegetarianism, opposed liquor and paid serious attention to any "-ism" anyone proposed. What made the ‘’Tribune’‘ such a success were the extensive news stories, very well written by brilliant reporters, together with feature articles by fine writers. He was an excellent judge of newsworthiness and quality of reporting. His editorials and news reports explaining the policies and candidates of the Whig Party were reprinted and discussed throughout the country. Many small newspapers relied heavily on the reporting and editorials of the Tribune. Greeley was noted for his eccentricities. His attire in even the hottest weather included a full-length coat, and he was never without an umbrella; his interests included spiritualism and phrenology.[5] He considered the word 'news' to be a plural word, and habitually corrected his staff when they asked, "Is there any news?" He once cabled a Tribune reporter: “ARE THERE ANY NEWS?” The employee cabled back: "NOT A NEW." He served as Congressman for three months, 1848–1849, but failed in numerous other attempts to win elective office. When the new Republican Party was founded in 1854, Greeley made the Tribune its unofficial national organ, and fought slavery extension and the slave power on many pages. On the eve of the Civil War circulation nationwide approached 300,000. In 1860 he supported the ex-Whig Edward Bates of Missouri for the Republican nomination for president, an action that weakened Greeley's old ally Seward.[Van Dusen 241-44] Greeley made the Tribune the leading newspaper opposing the Slave Power, that is, what he considered the conspiracy by slave owners to seize control of the federal government and block the progress of liberty. In the secession crisis of 1861 he took a hard line against the Confederacy. Theoretically, he agreed, the South could declare independence; but in reality he said there was "a violent, unscrupulous, desperate minority, who have conspired to clutch power"—secession was an illegitimate conspiracy that had to be crushed by federal power. He took a Radical Republican position during the war, in opposition to Lincoln’s moderation. In the summer of 1862, he wrote a famous editorial entitled "The Prayer of Twenty Millions" demanding a more aggressive attack on the Confederacy and faster emancipation of the slaves. A month later he hailed Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Although after 1860 he increasingly lost control of the Tribune’s operations, and wrote fewer editorials, in 1864 he expressed defeatism regarding Lincoln’s chances of reelection, an attitude that was echoed across the country when his editorials were reprinted. Oddly he also pursued a peace policy in 1863–64 that involved discussions with Copperheads and opened the possibility of a compromise with the Confederacy. Lincoln was aghast, but outsmarted Greeley by appointing him to a peace commission he knew the Confederates would repudiate. In Reconstruction he took an erratic course, mostly favoring the Radicals and opposing president Andrew Johnson in 1865–66. In 1867, Greeley was one of 21 men who signed a $100,000 bond for the release of former president of the Confederacy Jefferson Davis. The move was controversial, and many Northerners thought Greeley a traitor and canceled subscriptions to the Weekly Tribune by the thousands.[6] In 1869, he ran on the Republican ticket for New York State Comptroller but was defeated by the incumbent Democrat William F. Allen. After supporting Ulysses Grant in the 1868 election, Greeley broke from Grant and the Radicals. Opposing Grant's re-election bid, he joined the Liberal Republican Party in 1872. To everyone’s astonishment, that new party nominated Greeley as their presidential candidate. Even more surprisingly, he was officially endorsed by the Democrats, whose party he had denounced for decades. As a candidate, Greeley argued that the war was over, the Confederacy was destroyed, and slavery was dead—and that Reconstruction was a success, so it was time to pull Federal troops out of the South and let the people there run their own affairs. A weak campaigner, he was mercilessly ridiculed by the Republicans as a fool, an extremist, a turncoat, and a crazy man who could not be trusted. The most vicious attacks came in cartoons by Thomas Nast in Harper's Weekly. Greeley ultimately ran far behind Grant, winning only 43% of the vote. This crushing defeat was not Greeley's only misfortune in 1872. Greeley was among several high-profile investors who were defrauded by Philip Arnold in a famous diamond and gemstone hoax. Meanwhile, as Greeley had been pursuing his political career, Whitelaw Reid, owner of the New York Herald, had gained control of the Tribune. Not long after the election, Greeley's wife died. He descended into madness and died before the electoral votes could be cast. In his final illness, allegedly Greeley spotted Reid and cried out, "You son of a bitch, you stole my newspaper." Greeley died at 6:50 p.m. on Friday, November 29, 1872, in Pleasantville, New York at Dr. George C. S. Choate’s private hospital. Greeley would have received 66 electoral votes, which, because of his death, were scattered among others. However, three of Georgia's electoral votes were left blank in honor of him. (Other sources report Greeley receiving 3 electoral votes posthumously, with those votes being disallowed by Congress.) Although Greeley had requested a simple funeral, his daughters ignored his wishes and arranged a grand affair. He is buried in New York's Green-Wood Cemetery. The Greeley home in Chappaqua, New York, now houses the New Castle Historical Society. The local high school is named for him. Paying homage to the 19th-century paper owned by Greeley, the high school named its newspaper the Greeley Tribune.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

What I know of farming:a series of brief and plain expositions of practicalagriculture as an art based upon science

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Glances at EuropeIn a Series of Letters from Great Britain,France,Italy,Switzerland,&c. During the Summer of 1851.

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Glances at Europe

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Horace Greeley (1811 - 1872) was an American editor of a leading newspaper, a founder of the Liberal Republican Party, a reformer, and a politician. Greeley used his considerable influence to promote the Whig and Republican parties, as well as opposition to slavery. Glances at Europe In a Series of Letters from Great Britain, France, Italy, Switzerland, &c. During the Summer of 1851 is an excellent historical look into the social and political life in Europe.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

What I know of farming:a series of brief and plain expositions of practicalagriculture as an art based upon science

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Glances at EuropeIn a Series of Letters from Great Britain,France,Italy,Switzerland,&c. During the Summer of 1851.

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Glances at Europe

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Horace Greeley (1811 - 1872) was an American editor of a leading newspaper, a founder of the Liberal Republican Party, a reformer, and a politician. Greeley used his considerable influence to promote the Whig and Republican parties, as well as opposition to slavery. Glances at Europe In a Series of Letters from Great Britain, France, Italy, Switzerland, &c. During the Summer of 1851 is an excellent historical look into the social and political life in Europe.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Greeley Horace try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Greeley Horace try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!