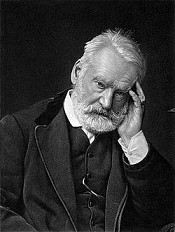

Hugo Victor

Victor-Marie Hugo (French pronunciation: [viktɔʁ maʁi yˈɡo]) (26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French poet, playwright, novelist, essayist, visual artist, statesman, human rights activist and exponent of the Romantic movement in France. In France, Hugo's literary fame comes first from his poetry but also rests upon his novels and his dramatic achievements. Among many volumes of poetry, Les Contemplations and La Légende des siècles stand particularly high in critical esteem, and Hugo is sometimes identified as the greatest French poet. Outside France, his best-known works are the novels Les Misérables and Notre-Dame de Paris (known in English also as The Hunchback of Notre Dame). Though a committed conservative royalist when he was young, Hugo grew more liberal as the decades passed; he became a passionate supporter of republicanism, and his work touches upon most of the political and social issues and artistic trends of his time. He is buried in the Panthéon. Victor Hugo was the third and last son of Joseph Léopold Sigisbert Hugo (1773–1828) and Sophie Trébuchet (1772-1821); his brothers were Abel Joseph Hugo (1798–1855) and Eugène Hugo (1800–1837). He was born in 1802 in Besançon (in the region of Franche-Comté) and lived in France for the majority of his life. However, he was forced into exile during the reign of Napoleon III — he lived briefly in Brussels during 1851; in Jersey from 1852 to 1855; and in Guernsey from 1855 to 1870 and again in 1872-1873. There was a general amnesty in 1859; after that, his exile was by choice. Hugo's early childhood was marked by great events. The decades prior to his birth saw the overthrow of the Bourbon Dynasty in the French Revolution, the rise and fall of the First Republic, and the rise of the First French Empire and dictatorship under Napoléon Bonaparte. Napoléon was proclaimed Emperor two years after Hugo's birth, and the Bourbon Monarchy was restored before his eighteenth birthday. The opposing political and religious views of Hugo's parents reflected the forces that would battle for supremacy in France throughout his life: Hugo's father was an officer who ranked very high in Napoleon's army. He was an atheist republican who considered Napoléon a hero; his mother was an extreme Catholic Royalist who is believed to have taken as her lover General Victor Lahorie, who was executed in 1812 for plotting against Napoléon. Since Hugo's father, Joseph, was an officer, they moved frequently and Hugo learned much from these travels. On his family's journey to Naples, he saw the vast Alpine passes and the snowy peaks, the magnificently blue Mediterranean, and Rome during its festivities. Though he was only nearly six at the time, he remembered the half-year-long trip vividly. They stayed in Naples for a few months and then headed back to Paris. Sophie followed her husband to posts in Italy (where Léopold served as a governor of a province near Naples) and Spain (where he took charge of three Spanish provinces). Weary of the constant moving required by military life, and at odds with her unfaithful husband, Sophie separated temporarily from Léopold in 1803 and settled in Paris. Thereafter she dominated Hugo's education and upbringing. As a result, Hugo's early work in poetry and fiction reflect a passionate devotion to both King and Faith. It was only later, during the events leading up to France's 1848 Revolution, that he would begin to rebel against his Catholic Royalist education and instead champion Republicanism and Freethought. Like many young writers of his generation, Hugo was profoundly influenced by François-René de Chateaubriand, the famous figure in the literary movement of Romanticism and France’s preëminent literary figure during the early 1800s. In his youth, Hugo resolved to be “Chateaubriand or nothing,” and his life would come to parallel that of his predecessor in many ways. Like Chateaubriand, Hugo would further the cause of Romanticism, become involved in politics as a champion of Republicanism, and be forced into exile due to his political stances. The precocious passion and eloquence of Hugo's early work brought success and fame at an early age. His first collection of poetry (Odes et poésies diverses) was published in 1822, when Hugo was only twenty years old, and earned him a royal pension from Louis XVIII. Though the poems were admired for their spontaneous fervor and fluency, it was the collection that followed four years later in 1826 (Odes et Ballades) that revealed Hugo to be a great poet, a natural master of lyric and creative song. Young Victor fell in love and against his mother's wishes, became secretly engaged to his childhood friend Adèle Foucher (1803-1868). Unusually close to his mother, it was only after her death in 1821 that he felt free to marry Adèle (in 1822). They had their first child Léopold in 1823, but the boy died in infancy. Hugo's other children were Léopoldine (28 August 1824), Charles (4 November 1826), François-Victor (28 October 1828) and Adèle (24 August 1830). Hugo published his first novel the following year (Han d'Islande, 1823), and his second three years later (Bug-Jargal, 1826). Between 1829 and 1840 he would publish five more volumes of poetry (Les Orientales, 1829; Les Feuilles d'automne, 1831; Les Chants du crépuscule, 1835; Les Voix intérieures, 1837; and Les Rayons et les ombres, 1840), cementing his reputation as one of the greatest elegiac and lyric poets of his time. Victor Hugo's first mature work of fiction appeared in 1829, and reflected the acute social conscience that would infuse his later work. Le Dernier jour d'un condamné (The Last Day of a Condemned Man) would have a profound influence on later writers such as Albert Camus, Charles Dickens, and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Claude Gueux, a documentary short story about a real-life murderer who had been executed in France, appeared in 1834, and was later considered by Hugo himself to be a precursor to his great work on social injustice, Les Misérables. But Hugo’s first full-length novel would be the enormously successful Notre-Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre Dame), which was published in 1831 and quickly translated into other languages across Europe. One of the effects of the novel was to shame the City of Paris into restoring the much-neglected Cathedral of Notre Dame, which was attracting thousands of tourists who had read the popular novel. The book also inspired a renewed appreciation for pre-renaissance buildings, which thereafter began to be actively preserved. Hugo began planning a major novel about social misery and injustice as early as the 1830s, but it would take a full 17 years for Les Misérables, to be realized and finally published in 1862. The author was acutely aware of the quality of the novel and publication of the work went to the highest bidder. The Belgian publishing house Lacroix and Verboeckhoven undertook a marketing campaign unusual for the time, issuing press releases about the work a full six months before the launch. It also initially published only the first part of the novel (“Fantine”), which was launched simultaneously in major cities. Installments of the book sold out within hours, and had enormous impact on French society. The critical establishment was generally hostile to the novel; Taine found it insincere, Barbey d'Aurevilly complained of its vulgarity, Flaubert found within it "neither truth nor greatness," the Goncourts lambasted its artificiality, and Baudelaire - despite giving favorable reviews in newspapers - castigated it in private as "tasteless and inept." Nonetheless, Les Misérables proved popular enough with the masses that the issues it highlighted were soon on the agenda of the French National Assembly. Today the novel remains his most enduringly popular work. It is popular worldwide, has been adapted for cinema, television and stage shows. The shortest correspondence in history is between Hugo and his publisher Hurst & Blackett in 1862. It is said Hugo was on vacation when Les Misérables (which is over 1200 pages) was published. He telegraphed the single-character message '?' to his publisher, who replied with a single '!'. Hugo turned away from social/political issues in his next novel, Les Travailleurs de la Mer (Toilers of the Sea), published in 1866. Nonetheless, the book was well received, perhaps due to the previous success of Les Misérables. Dedicated to the channel island of Guernsey where he spent 15 years of exile, Hugo’s depiction of Man’s battle with the sea and the horrible creatures lurking beneath its depths spawned an unusual fad in Paris: Squids. From squid dishes and exhibitions, to squid hats and parties, Parisians became fascinated by these unusual sea creatures, which at the time were still considered by many to be mythical. The word used in Guernsey to refer to squid (pieuvre, also sometimes applied to octopus) was to enter the French language as a result of its use in the book. Hugo returned to political and social issues in his next novel, L'Homme Qui Rit (The Man Who Laughs), which was published in 1869 and painted a critical picture of the aristocracy. However, the novel was not as successful as his previous efforts, and Hugo himself began to comment on the growing distance between himself and literary contemporaries such as Flaubert and Émile Zola, whose realist and naturalist novels were now exceeding the popularity of his own work. His last novel, Quatrevingt-treize (Ninety-Three), published in 1874, dealt with a subject that Hugo had previously avoided: the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution. Though Hugo’s popularity was on the decline at the time of its publication, many now consider Ninety-Three to be a work on par with Hugo’s better-known novels.[weasel words] After three unsuccessful attempts, Hugo was finally elected to the Académie française in 1841, solidifying his position in the world of French arts and letters. A group of French academiciens, particularly Etienne de Jouy was fighting against the "romantic evolution" and had managed to delay Victor Hugo's election [1]. Thereafter he became increasingly involved in French politics. He was elevated to the peerage by King Louis-Philippe in 1841 and entered the Higher Chamber as a pair de France, where he spoke against the death penalty and social injustice, and in favour of freedom of the press and self-government for Poland. However, he was also becoming more supportive of the Republican form of government and, following the 1848 Revolution and the formation of the Second Republic, was elected to the Constitutional Assembly and the Legislative Assembly.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

The Dramas of Victor Hugo: Mary Tudor,Marion de Lorme,Esmeralda

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

The Dramas of Victor Hugo: Mary Tudor,Marion de Lorme,Esmeralda

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Les misérables Tome IV

L'idylle rue Plumet et l'épopée rue Saint-Denis

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Man Who Laughs

A Romance of English History

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The History of a CrimeThe Testimony of an Eye-Witness

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

- Books

- Literature & Fiction / Literary

- Literature & Fiction / Poetry / General

- Religion & Spirituality / Christianity / Literature & Fiction / Fiction

- Biographies & Memoirs / Arts & Literature / Authors

- Nonfiction / Education / Education Theory / History

- Nonfiction / Foreign Language Nonfiction / German

- Reference / Atlases & Maps / World

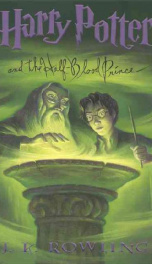

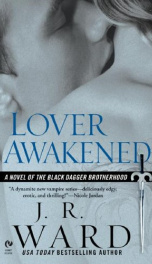

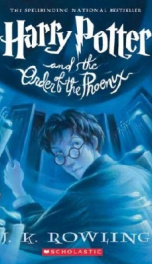

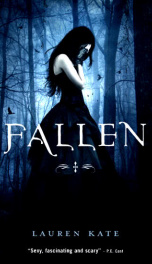

if you like Hugo Victor try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

- Books

- Literature & Fiction / Literary

- Literature & Fiction / Poetry / General

- Religion & Spirituality / Christianity / Literature & Fiction / Fiction

- Biographies & Memoirs / Arts & Literature / Authors

- Nonfiction / Education / Education Theory / History

- Nonfiction / Foreign Language Nonfiction / German

- Reference / Atlases & Maps / World

if you like Hugo Victor try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!