Kabir

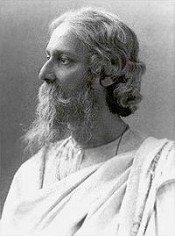

Rabindranath Tagore (Bengali: রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর)α[›]β[›] (7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941),γ[›] sobriquet Gurudev,δ[›] was a Bengali polymath. As a poet, novelist, musician, and playwright, he reshaped Bengali literature and music in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As author of Gitanjali and its "profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse",[1] he became Asia's first Nobel laureate by winning the 1913 Nobel Prize in Literature.[2] A Pirali Brahmin[3][4][5][6] from Calcutta, Tagore wrote poems at age eight.[7] At age sixteen, he published his first substantial poetry under the pseudonym Bhanushingho ("Sun Lion")[8] and wrote his first short stories and dramas in 1877. Tagore denounced the British Raj and supported the Indian Independence Movement. His efforts endure in his vast canon and in the institution he founded, Visva-Bharati University. Tagore modernised Bengali art by rejecting the strictures of rigid classical Indian forms. His novels, short stories, songs, dance-dramas, and essays ranged over political and personal topics alike. Gitanjali (Song Offerings), Gora (Fair-Faced), and Ghare-Baire (The Home and the World) are among his best-known works, and his verse, short stories, and novels were acclaimed for their lyricism, colloquialism, meditative naturalism, and philosophical contemplation. Two Tagore songs are the national anthems of Bangladesh and India: Amar Shonar Bangla and Jana Gana Mana. The youngest of thirteen surviving children, Tagore was born in the Jorasanko mansion in Calcutta of parents Debendranath Tagore (1817-1905) and Sarada Devi (1830-1875).ε[›][9] Tagore family patriarchs were the Brahmo founding fathers of the Adi Dharm faith. He was largely raised by servants, as his mother had died in his early childhood; his father travelled extensively.[10] Tagore largely declined classroom schooling, preferring to roam the mansion or explore idyllic vistas: Bolpur, Panihati, and others.[11][12] After his upanayan initiation at age eleven, Tagore left Calcutta on 14 February 1873 to tour India with his father for several months. They visited his father's Santiniketan estate and stopped in Amritsar before reaching the Himalayan hill station of Dalhousie. There, young "Rabi" read biographies, studied history, astronomy, modern science, and Sanskrit, and examined the classical poetry of Kālidāsa.[13][14] In 1877, he composed several major works, including a long poem set in the Maithili style pioneered by Vidyapati. As a joke, he maintained that these were the lost works of Bhānusiṃha, a newly discovered 17th-century Vaiṣṇava poet.[15] He also wrote "Bhikharini" (1877; "The Beggar Woman"—the Bengali language's first short story)[16][17] and Sandhya Sangit (1882) —including the famous poem "Nirjharer Swapnabhanga" ("The Rousing of the Waterfall"). A prospective barrister, Tagore enrolled at a public school in Brighton, East Sussex, England in 1878. He read law at University College London, but left school to explore Shakespeare and more: Religio Medici, Coriolanus, and Antony and Cleopatra;[18] he returned degree-less to Bengal in 1880. On 9 December 1883 he married Mrinalini Devi (born Bhabatarini, 1873–1900); they had five children, two of whom died before reaching adulthood.[19] In 1890, Tagore began managing his family's vast estates in Shilaidaha, a region now in Bangladesh; he was joined by his wife and children in 1898. Also in 1890, Tagore wrote Manast, a collection of poems that contains some of his best known poetry. He published several books of poetry while in his twenties.[20] As "Zamindar Babu", Tagore crisscrossed the holdings while living out of the family's luxurious barge, the Padma, to collect (mostly token) rents and bless villagers, who held feasts in his honour.[21] These years—1891–1895: Tagore's Sadhana period, named for one of Tagore’s magazines—were among his most fecund.[10] During this period, more than half the stories of the three-volume and eighty-four-story Galpaguchchha were written.[16] With irony and emotional weight, they depicted a wide range of Bengali lifestyles, particularly village life.[22] In 1901, Tagore left Shilaidaha and moved to Santiniketan to found an ashram, which would grow to include a marble-floored prayer hall ("The Mandir"), an experimental school, groves of trees, gardens, and a library.[23] There, Tagore's wife and two of his children died. His father died on 19 January 1905, and he began receiving monthly payments as part of his inheritance. He received additional income from the Maharaja of Tripura, sales of his family's jewellery, his seaside bungalow in Puri, and mediocre royalties (Rs. 2,000) from his works.[24] By now, his work was gaining him a large following among Bengali and foreign readers alike, and he published such works as Naivedya (1901) and Kheya (1906) while translating his poems into free verse. On 14 November 1913, Tagore learned that he had won the 1913 Nobel Prize in Literature. The Swedish Academy appreciated the idealistic and—for Western readers—accessible nature of a small body of his translated material, including the 1912 Gitanjali: Song Offerings.[25] In 1915, Tagore was knighted by the British Crown. In 1921, Tagore and agricultural economist Leonard Elmhirst set up the Institute for Rural Reconstruction (which Tagore later renamed Shriniketan—"Abode of Wealth") in Surul, a village near the ashram at Santiniketan. Through it, Tagore sought to provide an alternative to Gandhi's symbol- and protest-based Swaraj movement, which he denounced.[26] He recruited scholars, donors, and officials from many countries to help the Institute use schooling to "free village[s] from the shackles of helplessness and ignorance" by "vitalis[ing] knowledge".[27][28] In the early 1930s, he criticised India's "abnormal caste consciousness" and untouchability. He lectured against these, wrote poems and dramas with untouchable protagonists, and campaigned successfully to open Guruvayoor Temple to Dalits.[29][30] To the end, Tagore scrutinized orthodoxy. He upbraided Gandhi for declaring that a massive 15 January 1934 earthquake in Bihar—leaving thousands dead—was divine retribution brought on by the oppression of Dalits.[31] He mourned the endemic poverty of Calcutta and the accelerating socioeconomic decline of Bengal, which he detailed in an unrhymed hundred-line poem whose technique of searing double-vision would foreshadow Satyajit Ray's film Apur Sansar.[32][33] Fifteen new volumes of Tagore writings appeared, among them the prose-poems works Punashcha (1932), Shes Saptak (1935), and Patraput (1936). Experimentation continued: he developed prose-songs and dance-dramas, including Chitrangada (1914),[34] Shyama (1939), and Chandalika (1938), and wrote the novels Dui Bon (1933), Malancha (1934), and Char Adhyay (1934). Tagore took an interest in science in his last years, writing Visva-Parichay (a collection of essays) in 1937. His exploration of biology, physics, and astronomy impacted his poetry, which often contained extensive naturalism that underscored his respect for scientific laws. He also wove the process of science, including narratives of scientists, into many stories contained in such volumes as Se (1937), Tin Sangi (1940), and Galpasalpa (1941).[35] Tagore's last four years were marked by chronic pain and two long periods of illness. These began when Tagore lost consciousness in late 1937; he remained comatose and near death for an extended period. This was followed three years later in late 1940 by a similar spell, from which he never recovered. The poetry Tagore wrote in these years is among his finest, and is distinctive for its preoccupation with death.[36][37] After extended suffering, Tagore died on 7 August 1941 (22 Shravan 1348) in an upstairs room of the Jorasanko mansion in which he was raised;[38][39] his death anniversary is mourned across the Bengali-speaking world.[40] Between 1878 and 1932, Tagore visited more than thirty countries on five continents;[41] many of these trips were crucial in familiarising non-Indian audiences to his works and spreading his political ideas. In 1912, he took a sheaf of his translated works to England, where they impressed missionary and Gandhi protégé Charles F. Andrews, Anglo-Irish poet William Butler Yeats, Ezra Pound, Robert Bridges, Ernest Rhys, Thomas Sturge Moore, and others.[42] Indeed, Yeats wrote the preface to the English translation of Gitanjali, while Andrews joined Tagore at Santiniketan. On 10 November 1912, Tagore toured the United States[43] and the United Kingdom, staying in Butterton, Staffordshire with Andrews’ clergymen friends.[44] From 3 May 1916 until April 1917, Tagore went on lecturing circuits in Japan and the United States[45] and denounced nationalism.[46] He also wrote the essay "Nationalism in India", attracting both derision and praise (the latter from pacifists, including Romain Rolland).[47] Shortly after returning to India, the 63-year-old Tagore accepted the Peruvian government's invitation to visit. He then travelled to Mexico. Each government pledged $100,000 to the school at Shantiniketan (Visva-Bharati) in commemoration of his visits.[48] A week after his 6 November 1924 arrival in Buenos Aires, Argentina,[49] an ill Tagore moved into the Villa Miralrío at the behest of Victoria Ocampo. He left for India in January 1925. On 30 May 1926, Tagore reached Naples, Italy; he met fascist dictator Benito Mussolini in Rome the next day.[50] Their initially warm rapport lasted until Tagore spoke out against Mussolini on 20 July 1926.[51] On 14 July 1927, Tagore and two companions began a four-month tour of Southeast Asia, visiting Bali, Java, Kuala Lumpur, Malacca, Penang, Siam, and Singapore. Tagore's travelogues from the tour were collected into the work "Jatri".[53] In early 1930 he left Bengal for a nearly year-long tour of Europe and the United States. Once he returned to the UK, while his paintings were being exhibited in Paris and London, he stayed at a Friends settlement in Birmingham. There, he wrote his Hibbert Lectures for the University of Oxford (which dealt with the "idea of the humanity of our God, or the divinity of Man the Eternal") and spoke at London's annual Quaker gathering.[54] There (addressing relations between the British and Indians, a topic he would grapple with over the next two years), Tagore spoke of a "dark chasm of aloofness".[55] He later visited Aga Khan III, stayed at Dartington Hall, then toured Denmark, Switzerland, and Germany from June to mid-September 1930, then the Soviet Union.[56] Lastly, in April 1932, Tagore—who was acquainted with the legends and works of the Persian mystic Hafez—was hosted by Reza Shah Pahlavi of Iran.[57][58] Such extensive travels allowed Tagore to interact with many notable contemporaries, including Henri Bergson, Albert Einstein, Robert Frost, Thomas Mann, George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells and Romain Rolland.[59][60] Tagore's last travels abroad, including visits to Persia and Iraq (in 1932) and Ceylon in 1933, only sharpened his opinions regarding human divisions and nationalism.[61]

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Kabir try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Kabir try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!