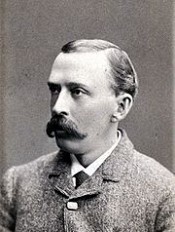

Kennan George

George Kennan (February 16, 1845 – 1924) was an American explorer noted for his travels in the Kamchatka and Caucasus regions of Russia. He was diplomat and historian George F. Kennan's cousin twice removed, with whom he shared his birthday. Kennan was born in Norwalk, Ohio, and was keenly interested in travel from an early age. However, family finances dictated that he begin work at the Cleveland and Toledo Railroad Company telegraph office at age twelve. In 1864, he secured employment with the Russian American Telegraph Company to survey a route for a proposed overland telegraph line through Siberia and across the Bering Strait. Having spent two years in the wilds of Kamchatka, he returned to Ohio via St. Petersburg and soon became well-known through his lectures, articles and book about his travels. He provided ethnographies, histories and descriptions of many native peoples in Siberia, that are still important for researchers today. They include stories about the Koraks (Koryak language), Kamchatdal (Itelmens), Chookchees, Yookaghirs, Chooances, Yakoots and Gakouts. In 1870, he returned to St. Petersburg and travelled to Dagestan, a northern area of the Caucasus region taken over by Russia only ten years previously. There he became the first American to explore its highlands, a remote Muslim region of herders, silversmiths, carpet-weavers and other craftsmen. He travelled on through the northern Caucasus area, stopping in Samashki and Grozny, before returning once more to America in 1871. In 1878, he became an Associated Press reporter based in Washington, D.C. In May 1885, Kennan began another voyage in Russia, this time across Siberia. He had been supportive of the Tsarist Russian government and its policies, but his meetings with exiled dissidents during his travel changed his mind. On his return to America in August 1886, he began to espouse the cause of revolution. He had been particularly impressed by Catherine Breshkovskaia, the populist "little grandmother of the Russian Revolution". She had bidden him farewell in the small Transbaikal village to which she was confined by saying "We may die in exile and our grand children may die in exile, but something will come of it at last." Kennan devoted much of the next twenty years to promoting the cause of Russian revolution, mainly through lecturing. In addition to Catherine Breshkovskaia, he befriended other émigrés such as Peter Kropotkin and Sergei Kravchinskii. He became the most prominent member of the Society of American Friends of Russian Freedom – whose membership included Mark Twain and Julia Ward Howe – and also helped found Free Russia, the first English-language journal to oppose Tsarist Russia. In 1891 the Russian government responded by banishing him from Russia. Kennan's campaigning on behalf of Russian political prisoners was later expanded to include persecuted minorities in the Russian empire, in particular the Jews and, following the Russo-Japanese War, the Japanese. Kennan also assisted a little-known campaign to educate and politically motivate Russian POWs held in Japan. Kennan was one of the most prolific lecturers of the late nineteenth century. He spoke before a million or so people during the 1890s, including two hundred consecutive evening appearances in 1890-91 (excepting Sundays) before crowds of as many as two thousand people. Kennan was vehemently against the October Revolution, because he felt the Soviet government lacked the "knowledge, experience, or education to deal successfully with the tremendous problems that have come up for solutions since the overthrow of the Tsar." Kennan criticized Woodrow Wilson for being too timid in intervening against Bolshevism. Despite questions on the accuracy of his journalism, his authority was unchallenged in the United States. Kennan presented a picture of Russia that was more a projection of characteristic American hopes, fantasies, and fears in an era of exuberant self-confidence than the product of hard-earned knowledge. His authority was based on firsthand observations, though they were largely focused on the exotic. He was sympathetic chiefly to political prisoners, who represented a minute fraction of those in Russia's vast penal and exile system. As far as we know, he never visited any prison outside Russia for comparative purposes. He confused political exiles in East Siberia with administrative exiles in West Siberia. At times he misled his audiences in other ways to dramatize his cause. Kennan never probed deeply into the views of Russians working within the system, who he could have helped and from whom he could have learned. What must be remembered is that his observations of native life, climate and language were based on personal observation, such as his descriptions of marriage ceremonies of the Koryats in 'Tent Life'. He was not a professional ethnographer. In fact, at the time, there were no professional ethnographers, nor was he a historian by trade, his work was completed under the most extreme conditions and thus bears the stamp of his own personal appraisal, much as found in work of his contemporaries such as Mark Twain.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

Tent Life in Siberia

A New Account of an Old Undertaking; Adventures among the Koraks and Other Tribes In Kamchatka and Northern Asia

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

the salton sea electronic resource an account of harrimans fight with the c

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

the chicago alton case a misunderstood transaction

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Originally published in 1916. This volume from the Cornell University Library's print collections was scanned on an APT BookScan and converted to JPG 2000 format by Kirtas Technologies. All titles scanned cover to cover and pages may include marks notations and other marginalia present in the original volume.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

Tent Life in Siberia

A New Account of an Old Undertaking; Adventures among the Koraks and Other Tribes In Kamchatka and Northern Asia

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

the salton sea electronic resource an account of harrimans fight with the c

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

the chicago alton case a misunderstood transaction

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Originally published in 1916. This volume from the Cornell University Library's print collections was scanned on an APT BookScan and converted to JPG 2000 format by Kirtas Technologies. All titles scanned cover to cover and pages may include marks notations and other marginalia present in the original volume.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

siberia and the exile system volume 2

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

This Elibron Classics book is a facsimile reprint of a 1891 edition by the Century Co., New York.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

siberia and the exile system volume 1

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

This Elibron Classics book is a facsimile reprint of a 1891 edition by the Century Co., New York.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

misrepresentation in railroad affairs

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

The Shelf2Life Trains & Railroads Collection provides a unique opportunity for researchers and railroad enthusiasts to easily access and explore pre-1923 titles focusing on the history, culture and experience of railroading. From the revolution of the steam engine to the thrill of early travel by rail, railroads opened up new opportunities for commerce, American westward expansion and travel. These books provide a unique view of the impact of this type of transportation on our urban and rural societies and cultures, while allowing the reader to share the experience of early railroading in a new and unique way. The Trains & Railroads Collection offers a valuable perspective on this important and fascinating aspect of modern industrialization.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

campaigning in cuba

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Purchase of this book includes free trial access to www.million-books.com where you can read more than a million books for free. This is an OCR edition with typos. Excerpt from book: CHAPTER III ON THE EDGE OF WAR UNTIL the illuminating search-light of war was turned upon the island of Key West, it was, to the people of the North generally, little more than a name attached to a small, arid coral reef lying on the verge of the Gulf Stream off the southern extremity of Florida. Few people knew anything definitely about it, and to nine readers out of ten its name suggested nothing more interesting or attractive than Cuban filibusters, sponges, and cigars. In less than a month, however, after the outbreak of hostilities, it had become the headquarters, as well as the chief coaling-station, of two powerful fleets; the news-distributing center for the whole Cuban coast; the supply-depot to which perhaps a hundred vessels resorted for water, food, and ammunition; the home station of all the newspaper despatch-boats cruising in West Indian waters; the temporary headquarters of more than a hundred newspaper correspondents and reporters, and the most advanced outpost of the United States on the edge of war. In view of the importance which the place had at that time, as well as the importance which it must continue to have, as our naval base in Cuban waters, a description of it may not be wholly without interest. The island on which the city of Key West stands forms one of the links in a long, curving chain of shoals, reefs, andkeys extending in a southwesterly direction about a hundred miles from the extreme end of the peninsula of Florida. It is approximately six miles long, has an average width of one mile, and resembles a little in shape a huge comma, with the city of Key West for its head and a diminishing curve of low, swampy chaparral and mangrove-bushes for a tail. The shallow bay of pale-green water between the head and the tail on the concave side of the...

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Kennan George try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Kennan George try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!