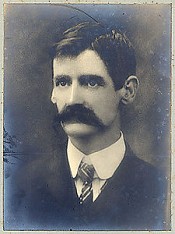

Lawson Henry

Henry Lawson (17 June 1867 – 2 September 1922) was an Australian writer and poet . Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial period, and is often called Australia's "greatest writer".[1] Henry Lawson was born in a town on the Grenfell goldfields of New South Wales. His father was Niels Herzberg Larsen, a Norwegian-born miner who went to sea at 21 and arrived in Melbourne in 1855 to join the gold rush.[2] Lawson's parents met at the goldfields of Pipeclay (now Eurunderee, New South Wales) Niels and Louisa Albury (1848 - 1920) married on 7 July 1866; he was 32 and she, 18. On Henry's birth, the family surname was anglicised and Niels became Peter Lawson. The newly-married couple were to have an unhappy marriage. Louisa, after family-raising, took a significant part in women's movements, and edited a women's paper called Dawn (published May 1888 to July 1905). She also published her son's first volume, and around 1904 brought out a volume of her own, Dert and Do, a simple story of 18,000 words. In 1905 she collected and published her own verses, The Lonely Crossing and other Poems. Louisa likely had a strong influence on her son's literary work in its earliest days[3]. Peter Larsen's grave (with headstone) is in the little private cemetery at Hartley Vale, New South Wales, a few minutes' walk behind what was Collitt's Inn. Henry Lawson attended school at Eurunderee from 2 October 1876 but suffered an ear infection at around this time. It left him with partial deafness and by the age of fourteen he had lost his hearing entirely. However, his master John Tierney was kind and seems to have done his best for Lawson who was quite shy.[3] Lawson later attended a Catholic school at Mudgee, New South Wales around 8 km away; the master there, Mr. Kevan, would teach Lawson about poetry. Lawson was a keen reader of Dickens and Marryat and serialised novels such as Robbery under Arms and For the Term of his Natural Life; an aunt had also given him a volume by Bret Harte. Reading became a major source of his education because, due to his deafness, he had trouble learning in the classroom. In 1883, after working on building jobs with his father and in the Blue Mountains, Lawson joined his mother in Sydney at her request. Louisa was then living with Henry's sister and brother. At this time, Lawson was working during the day and studying at night for his matriculation in the hopes of receiving a university education. However, he failed his exams. At around 20 years of age Lawson went to the eye and ear hospital in Melbourne but nothing could be done for his deafness.[3] In 1896, Lawson married Bertha Bredt Jr., daughter of Bertha Bredt, the prominent socialist. The marriage was ill-advised due to Lawson's alcohol addiction. They had two children, son Jim (Joseph) and daughter Bertha. However, the marriage ended unhappily.[4] Lawson's first published poem was 'A Song of the Republic' which appeared in The Bulletin, 1 October 1887; his mother's radical friends were an influence. This was followed by 'The Wreck of the Derry Castle' and then 'Golden Gully.' Prefixed to the former poem was an editorial note: Lawson was actually 20 years old, not 17, but the editor showed good judgment in recognizing the poet's ability so early.[3] In 1890-1891 Lawson worked in Albany.[5] He then received an offer to write for the Brisbane Boomerang in 1891, but he lasted only around 7-8 months as the Boomerang was soon in trouble. He returned to Sydney and continued to write for the Bulletin which, in 1892, paid for an inland trip where he experienced the harsh realities of drought-affected New South Wales.[6] This resulted in his contributions to the Bulletin Debate and became a source for many of his stories in subsequent years.[2] Elder writes of the trek Lawson took between Hungerford and Bourke as "the most important trek in Australian literary history" and says that "it confirmed all his prejudices about the Australian bush. Lawson had no romantic illusions about a 'rural idyll'."[7] As Elder continues, his grim view of the outback was far removed from "the romantic idyll of brave horsemen and beautiful scenery depicted in the poetry of 'The Banjo' [Paterson]".[8] Lawson's most successful prose collection is While the Billy Boils, published in 1896.[9] In it he "continued his assault on Paterson and the romantics, and in the process, virtually reinvented Australian realism".[6] Elder writes that "he used short, sharp sentences, with language as raw as Ernest Hemingway or Raymond Carver. With sparse adjectives and honed-to-the-bone description, Lawson created a style and defined Australians: dryly laconic, passionately egalitarian and deeply humane."[6] Most of his work focuses on the Australian bush, such as the desolate "Past Carin'", and is considered by some to be among the first accurate descriptions of Australian life as it was at the time. "The Drover's Wife" with its "heart-breaking depiction of bleakness and loneliness" is regarded as one of his finest short stories.[6] It is regularly studied in schools and has often been adapted for film and theatre.[10][11][12] Lawson was a firm believer in the merits of the sketch story, commonly known simply as 'the sketch,' claiming that "the sketch story is best of all."[13][14] Lawson's Jack Mitchell story, On The Edge Of A Plain, is often cited as one of the most accomplished examples of the sketch.[14] Like the majority of Australians, Lawson lived in a city, but had had plenty of experience in outback life, in fact, many of his stories reflected his experiences in real life. In Sydney in 1898 he was a prominent member of the Dawn and Dusk Club, a bohemian club of writer friends who met for drinks and conversation. During his later life, the alcohol-addicted writer was probably Australia's best-known celebrity. At the same time, he was also a frequent beggar on the streets of Sydney, notably at the Circular Quay ferry turnstiles. In 1903 he sought a room at Mrs Isabella Byers' Coffee Palace in North Sydney. This marked the beginning of a 20 year friendship between Mrs Byers and Lawson. Despite his position as the most celebrated Australian writer of the time, Lawson was deeply depressed and perpetually poor. He lacked money due to unfortunate royalty deals with publishers. His ex-wife repeatedly reported him for non-payment of child maintenance, resulting in gaol terms. He was gaoled at Darlinghurst Gaol for drunkenness and non-payment of alimony, and recorded his experience in the haunting poem "One Hundred and Three" - his prison number - which was published in 1908. He refers to the prison as "Starvinghurst Gaol" because of the meagre rations given to the inmates. At this time, Lawson became withdrawn, alcoholic, and unable to carry on the usual routine of life. Mrs Byers (nee Ward) was an excellent poet herself and although of modest education, had been writing vivid poetry since her teens in a similar style to Lawson's. Long separated from her husband and elderly, Mrs Bryers was, at the time she met Lawson, a woman of independent means looking forward to retirement. Bryers regarded Lawson as Australia's greatest living poet, and hoped to sustain him well enough to keep him writing. She negotiated on his behalf with publishers, helped to arrange contact with his children, contacted friends and supporters to help him financially, and assisted and nursed him through his mental and alcohol problems. She wrote countless letters on his behalf and knocked on any doors that could provide Henry with financial assistance or a publishing deal. [Olive Lawson The Good Wards of Windsor Deerubbin Press 2004]. It was in Mrs Isabella Bryers' home that Henry Lawson died, of cerebral haemorrhage, in Abbotsford, Sydney in 1922. He was given a state funeral. His death registration on the NSW Births, Deaths & Marriages index is ref. 10451/1922 and was recorded at the Petersham Registration District. It shows his parents as Peter and Louisa. His funeral was attended by the Prime Minister W. M. Hughes and the Premier of New South Wales Jack Lang (who was the husband of Lawson's sister-in-law Hilda Bredt), as well as thousands of citizens. He is interred at Waverley Cemetery. Lawson was the first person to be granted a New South Wales state funeral (traditionally reserved for Governors, Chief Justices, etc.) on the grounds of having been a 'distinguished citizen'.[15] Henry Lawson was featured on the first (paper) Australian ten dollar note issued in 1966 when decimal currency was first introduced into Australia. This note was replaced by a polymer note in 1993. Lawson was pictured against scenes from the town of Gulgong in NSW.[16] Many of Henry Lawson's short stories explore similar themes:

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

verses popular and humorous

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Henry Lawson (1867-1922) was an Australian writer and poet. He is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial period. Lawson was born in a town on the Grenfell goldfields of New South Wales. He attended school at Eurunderee from 1876 but suffered an ear infection at around this time that left him with partial deafness and by the age of fourteen he had lost his hearing entirely. He later attended a Catholic school at Mudgee, New South Wales. He was a keen reader of Dickens and Marryat and serialised novels such as Robbery Under Arms and For the Term of His Natural Life. Lawson's first published poem was A Song of the Republic which appeared in The Bulletin, 1887. This was followed by The Wreck of the Derry Castle and then Golden Gully. Most of his work focuses on the Australian bush, such as the desolate Past Carin, and is considered by some to be among the first accurate descriptions of Australian life as it was at the time. --This text refers to the Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Rising of the Court

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

This book was converted from its physical edition to the digital format by a community of volunteers. You may find it for free on the web. Purchase of the Kindle edition includes wireless delivery.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

verses popular and humorous

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Henry Lawson (1867-1922) was an Australian writer and poet. He is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial period. Lawson was born in a town on the Grenfell goldfields of New South Wales. He attended school at Eurunderee from 1876 but suffered an ear infection at around this time that left him with partial deafness and by the age of fourteen he had lost his hearing entirely. He later attended a Catholic school at Mudgee, New South Wales. He was a keen reader of Dickens and Marryat and serialised novels such as Robbery Under Arms and For the Term of His Natural Life. Lawson's first published poem was A Song of the Republic which appeared in The Bulletin, 1887. This was followed by The Wreck of the Derry Castle and then Golden Gully. Most of his work focuses on the Australian bush, such as the desolate Past Carin, and is considered by some to be among the first accurate descriptions of Australian life as it was at the time. --This text refers to the Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Rising of the Court

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

This book was converted from its physical edition to the digital format by a community of volunteers. You may find it for free on the web. Purchase of the Kindle edition includes wireless delivery.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Over the Sliprails

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

First published 1900. Author was one of Australia's best-known poets and fiction writers of the "Colonial period" and is often called Australia's greatest short story writer.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

On the Track

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

First published 1900. Author was one of Australia's best-known poets and fiction writers of the "Colonial period" and is often called Australia's greatest short story writer.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Joe Wilson and His Mates

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Henry Lawson (1867-1922) was an Australian writer and poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial period. Most of his work focuses on the Australian bush. Lawson was a firm believer in the merits of the sketch story, commonly known simply as 'the sketch,' claiming that "the sketch story is best of all." Like the majority of Australians, Lawson lived in a city, but had had plenty of experience in outback life, in fact, many of his stories reflected his experiences in real life. In Sydney in 1898 he was a prominent member of the Dawn and Dusk Club, a bohemian club of writer friends who met for drinks and conversation. --This text refers to an alternate Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

In the Days When the World Was Wide and Other Verses

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Henry Lawson (1867-1922) was an Australian writer and poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial period. Most of his work focuses on the Australian bush. Lawson was a firm believer in the merits of the sketch story, commonly known simply as 'the sketch,' claiming that "the sketch story is best of all." Like the majority of Australians, Lawson lived in a city, but had had plenty of experience in outback life, in fact, many of his stories reflected his experiences in real life. In Sydney in 1898 he was a prominent member of the Dawn and Dusk Club, a bohemian club of writer friends who met for drinks and conversation. Among his famous works are: In the Days When the World Was Wide (1896), While the Billy Boils (1896), Over the Sliprails (1900), On the Track (1900), Joe Wilson and His Mates (1901), Children of the Bush (1902), and The Rising of the Court (1910). --This text refers to an alternate Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Lawson Henry try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Lawson Henry try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!