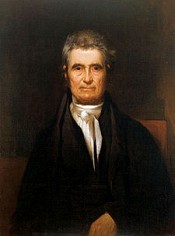

Marshall John

John Marshall (September 24, 1755 – July 6, 1835) was an American statesman and jurist who shaped American constitutional law and made the Supreme Court a center of power. Marshall was Chief Justice of the United States, serving from February 4, 1801, until his death in 1835. He served in the United States House of Representatives from March 4, 1799, to June 7, 1800, and, under President John Adams, was Secretary of State from June 6, 1800, to March 4, 1801. Marshall was from the Commonwealth of Virginia and a leader of the Federalist Party. The longest serving Chief Justice in Supreme Court history, Marshall dominated the Court for over three decades (a term outliving his own Federalist Party) and played a significant role in the development of the American legal system. Most notably, he established that the courts are entitled to exercise judicial review, the power to strike down laws that violate the Constitution. Thus, Marshall has been credited with cementing the position of the judiciary as an independent and influential branch of government. Furthermore, Marshall made several important decisions relating to Federalism, shaping the balance of power between the federal government and the states during the early years of the republic. In particular, he repeatedly confirmed the supremacy of federal law over state law and supported an expansive reading of the enumerated powers. John Marshall was born in a log cabin near Germantown, a rural community on the Virginia frontier, in what is now Fauquier County near Midland, Virginia, to Thomas Marshall and Mary Randolph Keith. From a young age, he was noted for his good humor and black eyes, which were "strong and penetrating, beaming with intelligence and good nature".[1] Marshall served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War and was friends with George Washington. He served first as a Lieutenant in the Culpeper Minute Men from 1775 to 1776, then as a Lieutenant in the Eleventh Virginia Continental Regiment from 1776 to 1780.[2] During his time in the army, he enjoyed running races with the other soldiers and was nicknamed "Silverheels" for the white heels his mother had sewn into his stockings.[3] After his time in the Army, he read law under the famous Chancellor George Wythe in Williamsburg, Virginia at the College of William and Mary,[4] was elected to Phi Beta Kappa[5] and was admitted to the Bar in 1780.[2] He was in private practice in Fauquier County, Virginia[2] before entering politics. In 1782 Marshall won a seat in the Virginia House of Delegates, in which he served until 1789 and again from 1795–1796. The Virginia General Assembly elected him to serve on the Council of State later in the same year. In 1785, Marshall took up the additional office of Recorder of the Richmond City Hustings Court.[6] In 1788, Marshall was selected as a delegate to the Virginia convention responsible for ratifying or rejecting the United States Constitution, which had been proposed by the Philadelphia Convention a year earlier. Together with James Madison and Edmund Randolph, Marshall led the fight for ratification. He was especially active in defense of Article III, which provides for the Federal judiciary.[7] His most prominent opponent at the ratification convention was Anti-Federalist leader Patrick Henry. Ultimately, the convention approved the Constitution by a vote of 89-79. Marshall identified with the new Federalist Party (which supported a strong national government and commercial interests), rather than Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party (which advocated states' rights and idealized the yeoman farmer and the French Revolution). Meanwhile, Marshall's private law practice continued to flourish. He successfully represented the heirs of Lord Fairfax in Hite v. Fairfax (1786), an important Virginia Supreme Court case involving a large tract of land in the Northern Neck of Virginia. In 1796, he appeared before the United States Supreme Court in another important case, Ware v. Hylton, a case involving the validity of a Virginia law providing for the confiscation of debts owed to British subjects. Marshall argued that the law was a legitimate exercise of the state's power; however, the Supreme Court ruled against him, holding that the Treaty of Paris required the collection of such debts.[8] In 1795, Marshall declined Washington's offer of Attorney General of the United States and, in 1796, declined to serve as minister to France. In 1797, he accepted when President John Adams appointed him to a three-member commission to represent the United States in France. (The other members of this commission were Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Elbridge Gerry.) However, when the envoys arrived, the French refused to conduct diplomatic negotiations unless the United States paid enormous bribes. This diplomatic scandal became known as the XYZ Affair, inflaming anti-French opinion in the United States. Hostility increased even further when the Directoire expelled Marshall and Pinckney from France. Marshall's handling of the affair, as well as public resentment toward the French, made him popular with the American public when he returned to the United States.[8] In 1798, Marshall declined a Supreme Court appointment, recommending Bushrod Washington, who would later become one of Marshall's staunchest allies on the Court.[9] In 1799, Marshall reluctantly ran for a seat in the United States House of Representatives. Although his congressional district (which included the city of Richmond) favored the Democratic-Republican Party, Marshall won the race, in part due to his conduct during the XYZ Affair and in part due to the support of Patrick Henry. His most notable speech was related to the case of Thomas Nash (alias Jonathan Robbins), whom the government had extradited to Great Britain on charges of murder. Marshall defended the government's actions, arguing that nothing in the Constitution prevents the United States from extraditing one of its citizens.[10] On May 7, 1799, President Adams nominated Congressman Marshall as Secretary of War. However, on May 12, Adams withdrew the nomination, instead naming him Secretary of State, as a replacement for Timothy Pickering. Confirmed by the United States Senate on May 13, Marshall took office on June 6, 1800. As Secretary of State, Marshall directed the negotiation of the Convention of 1800, which ended the Quasi-War with France and brought peace to the new nation. Marshall was thrust into the office of Chief Justice in the wake of the presidential election of 1800. With the Federalists soundly defeated and about to lose both the executive and legislative branches to Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans, President Adams and the lame duck Congress passed what came to be known as the Midnight Judges Act, which made sweeping changes to the federal judiciary, including a reduction in the number of Justices from six to five so as to deny Jefferson an appointment until two vacancies occurred.[11] As the incumbent Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth was in poor health, Adams first offered the seat to ex-Chief Justice John Jay, who declined on the grounds that the Court lacked "energy, weight, and dignity."[12] Jay's letter arrived on January 20, 1801, and as there was precious little time left, Adams nominated Marshall, who was with him at the time and able to accept immediately. The Senate at first delayed, hoping to Adams would make a different choice, but recanted "lest another not so qualified, and more disgusting to the Bench, should be substituted, and because it appeared that this gentleman was not privy to his own nomination".[13] Marshall was confirmed by the Senate on January 27, 1801, and received his commission on January 31, 1801.[2] While Marshall officially took office on February 4, at the request of the President he continued to serve as Secretary of State until Adams' term expired on March 4. Soon after becoming Chief Justice, Marshall changed the manner in which the Supreme Court announced its decisions. Previously, each Justice would author a separate opinion (known as a seriatim opinion), as is still done in the 20th and 21st centuries in such jurisdictions as the United Kingdom and Australia. Under Marshall, however, the Supreme Court adopted the practice of handing down a single opinion of the Court. As Marshall was almost always the author of this opinion, he essentially became the Court's sole mouthpiece in important cases. His forceful personality allowed him to dominate his fellow Justices; only once did he find himself on the losing side. (The case of Ogden v. Saunders, in 1827, was the sole constitutional case in which he dissented from the majority.)[9] The first important case of Marshall's career was Marbury v. Madison (1803), in which the Supreme Court invalidated a provision of the Judiciary Act of 1789 on the grounds that it violated the Constitution by attempting to expand the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. Marbury was the first case in which the Supreme Court ruled an act of Congress unconstitutional; it firmly established the doctrine of judicial review. The Court's decision was opposed by President Thomas Jefferson, who lamented that this doctrine made the Constitution "a mere thing of wax in the hands of the judiciary, which they may twist and shape into any form they please."[14] In 1807, he presided, with Judge Cyrus Griffin, at the great state trial of former Vice President Aaron Burr, who was charged with treason and misdemeanor. Prior to the trial, President Jefferson condemned Burr and strongly supported conviction. Marshall, however, narrowly construed the definition of treason provided in Article III of the Constitution; he noted that the prosecution had failed to prove that Burr had committed an "overt act," as the Constitution required. As a result, the jury acquitted the defendant, leading to increased animosity between the President and the Chief Justice.[15] During the 1810s and 1820s, Marshall made a series of decisions involving the balance of power between the federal government and the states, where he repeatedly affirmed federal supremacy. For example, he established in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) that states could not tax federal institutions and upheld congressional authority to create the Second Bank of the United States, even though the authority to do this was not expressly stated in the Constitution. Also, in Cohens v. Virginia (1821), he established that the Federal judiciary could hear appeals from decisions of state courts in criminal cases as well as the civil cases over which the court had asserted jurisdiction in Martin v. Hunter's Lessee (1816). Justices Bushrod Washington and Joseph Story proved to be his strongest allies in these cases, whereas Smith Thompson was a strong opponent to Marshall.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

Opinion of the Supreme Court of the United States,at January Term,1832,Delivered by Mr. Chief Justice Marshall in the Case of Samuel A. Worcester,Plaintiff in Error,versus the State of Georgia

With a Statement of the Case,Extracted from the Records of the

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Life Of George WashingtonA Linked Index to the Project Gutenberg Editions

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Life of George Washington,Vol. 5

Commander in Chief of the American Forces During the War

which Established the Independence of his Country and First

President of the United States

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

Opinion of the Supreme Court of the United States,at January Term,1832,Delivered by Mr. Chief Justice Marshall in the Case of Samuel A. Worcester,Plaintiff in Error,versus the State of Georgia

With a Statement of the Case,Extracted from the Records of the

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Life Of George WashingtonA Linked Index to the Project Gutenberg Editions

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Life of George Washington,Vol. 5

Commander in Chief of the American Forces During the War

which Established the Independence of his Country and First

President of the United States

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Life of George Washington,Vol. 4

Commander in Chief of the American Forces During the War

which Established the Independence of his Country and First

President of the United States

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Life of George Washington,Vol. 3

Commander in Chief of the American Forces During the War

which Established the Independence of his Country and First

President of the United States

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Life of George Washington,Vol. 2

Commander in Chief of the American Forces During the War

which Established the Independence of his Country and First

President of the United States

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Life of George Washington,Vol. 1

Commander in Chief of the American Forces During the War

which Established the Independence of his Country and First

President of the United States

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

the political and economic doctrines of john marshall who for thirty four years

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

This scarce antiquarian book is included in our special Legacy Reprint Series. In the interest of creating a more extensive selection of rare historical book reprints, we have chosen to reproduce this title even though it may possibly have occasional imperfections such as missing and blurred pages, missing text, poor pictures, markings, dark backgrounds and other reproduction issues beyond our control. Because this work is culturally important, we have made it available as a part of our commitment to protecting, preserving and promoting the world's literature. --This text refers to the Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

notes on the chemical lectures for second year students in the medical departmen

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

narrative of the naval operations in ava during the burmese war in the years 1

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a history of the colonies planted by the english on the continent of north ameri

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

A Short History of Greek Philosophy

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Purchase of this book includes free trial access to www.million-books.com where you can read more than a million books for free. This is an OCR edition with typos. Excerpt from book: CHAPTER V THE ELEATICS (concluded) 106 III. Zeno.The third head of the Eleatic school was ZENO. He is described by Plato in the Parmenides as accompanying his master to Athens on the visit already referred to (see above, p. 34), and as being then " nearly forty years of age, of a noble figure and fair aspect." In personal character he was a worthy pupil of his master, being, like him, a devoted patriot. He is even said to have fallen a victim to his patriotism, and to have suffered bravely the extremest tortures at the hands of a tyrant Nearchus rather than betray his country. His philosophic position was a very simple one. He had nothing to add to or to vary in the doctrine of Parmenides. His function was primarily that of an expositor and defender of that doctrine, and his particular pre-eminence consists in the ingenuity of his dialectic resources of defence. He is in fact pronounced by Aristotle to have been the inventor of dialectic or systematic logic. The relation ofZENO'S DIALECTIC 43 the two is humorously expressed thus by Plato (Jowett, Plato, vol. iv. p. 128): "I see, Parmenides, said Socrates, that Zeno is your second self in his writings too ; he puts what you say in another way, and would fain deceive us into believing that he is telling us what is new. For you, in your poems, say, All is one, and of this you adduce excellent proofs ; and he, on the other hand, says, There is no many ; and on behalf of this he offers overwhelming evidence." To this Zeno replies, admitting the fact, and adds: " These writings of mine were meant to protect the arguments of Parmenides against those who scoff at him, and show the many ridiculous and contradictory results which they suppose to follow from the affirmation of the One. My answer is an address to the partisans of t...

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Opinion of the Supreme Court of the United States, at January Term, 1832, Delivered by Mr. Chief Justice Marshall in the Case of Samuel A. Worcester, Plaintiff in Error, versus the State of Georgia

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Life of George Washington, Vol. 5 (of 5)

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

This book was converted from its physical edition to the digital format by a community of volunteers. You may find it for free on the web. Purchase of the Kindle edition includes wireless delivery.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Life of George Washington, Vol. 4 (of 5)

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

This book was converted from its physical edition to the digital format by a community of volunteers. You may find it for free on the web. Purchase of the Kindle edition includes wireless delivery.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Life of George Washington, Vol. 3 (of 5)

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

This book was converted from its physical edition to the digital format by a community of volunteers. You may find it for free on the web. Purchase of the Kindle edition includes wireless delivery.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Marshall John try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Marshall John try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!