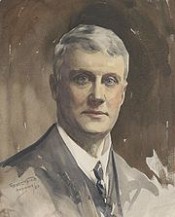

Morrison George Ernest

George Ernest Morrison (4 February 1862 – 30 May 1920), also known as Chinese Morrison, was an Australian adventurer and The Times Peking correspondent. Morrison was born in Geelong, Victoria, Australia. His father George Morrison (brother of Alexander Morrison) was headmaster of The Geelong College at which school the boy was educated. During a vacation before his tertiary education, he walked from Geelong to Adelaide, a distance of about 600 miles (960 km). He initially studied at the University of Melbourne. After passing his first year medicine he took a vacation trip down the Murray River in a canoe from Albury, New South Wales to the mouth, a distance of 1650 miles (2,640 km), covered in 65 days. Failing in his next examinations he shipped on a vessel trading to the South Sea islands, discovered some of the evils of the kanaka traffic, and wrote articles on it which appeared in The Age and had some influence on the eventual suppression of it. He next visited New Guinea and did part of the return journey on a Chinese junk. Landing at Normanton, Queensland at the end of 1882 Morrison decided to walk to Melbourne. He was not quite 21, he had no horses or camels and was unarmed, but carrying his swag and swimming or wading the rivers in his path, he walked the 2043 miles (3270 km) in 123 days. No doubt the country had been much opened up since the days of Burke and Wills, but the journey was nevertheless a remarkable feat, which stamped Morrison as a great natural bushman and explorer. He arrived at Melbourne on 21 April 1883 to find that during his journey Thomas McIlwraith, the premier of Queensland, had annexed part of New Guinea, and was vainly endeavouring to get the support of the British government for his action. Financed by The Age and the Sydney Morning Herald, Morrison was sent on an exploration journey to New Guinea. He sailed from Cooktown, Queensland in a small lugger, arriving at Port Moresby after a stormy passage. On 24 July 1883 Morrison with a small party started with the intention of crossing to Dyke Acland Bay 100 miles (160 km) away. Much high mountain country barred the way, and it took 38 days to cover 50 miles. The natives became hostile, and about a month later Morrison was struck by two spears and almost killed. Retracing their steps, with Morrison strapped to a horse, Port Moresby was reached in days. Here Morrison received medical attention but it was more than a month before he reached the hospital at Cooktown. In spite of his misfortune Morrison had penetrated farther into New Guinea than any previous white man. Much the better for a week in hospital Morrison went on to Melbourne, but he still carried the head of a spear in his body and no local surgeon was anxious to probe for it in the condition of surgery in that day. Morrison's father decided to send the young man to John Chiene, professor of surgery at Edinburgh university, the operation was successful, and Morrison took up his medical studies again, at Edinburgh. He graduated M.B. Ch.M. on 1 August 1887. After his graduation Morrison travelled extensively in the United States, the West Indies, and Spain, where he became medical officer at the Rio Tinto mine. He then proceeded to Morocco, became physician to the Shereef of Wazan, and did some travelling in the interior. Study at Paris under Dr Charcot followed before he returned to Australia in 1890, and for two years was resident surgeon at the Ballarat, Victoria hospital. Leaving the hospital in May 1893 he went to the Far East, and in February 1894 began a journey from Shanghai to Rangoon. He went partly by boat up the Yangtze River and rode and walked the remainder of the 3000 miles (4800 km). He completed the journey in 100 days at a total cost of £18, which included the wages of two or three Chinese servants whom he picked up and changed on the way as he entered new districts. He was quite unarmed and then knew hardly more than a dozen words of Chinese. But he was willing to conform to and respect the customs of the people he met, and everywhere was received with courtesy. After his arrival at Rangoon, Morrison went to Calcutta where he became seriously ill with remittant fever and nearly died. On recovering he went to Scotland, presented a thesis to the University of Edinburgh on "Heredity as a Factor in the Causation of Disease", and received his M.D. degree in August 1895. He was introduced to Moberly Bell, editor of The Times, who appointed him a special correspondent in the east. In November he went to Siam where there were Anglo-French difficulties, and travelled much in the interior. Morrison was very doubtful about his first communication to The Times and showed it to a friend who, in a letter to The Times about the time of Morrison's death, spoke of it as a perfect diagnosis of the then troubled condition of China, masterly in its phrasing, luminous in its broad conception of the general situation". His reports attracted much attention both in London and Paris. From Siam he crossed into southern China and at Yunnan was again seriously ill. Curing himself he made his way through Siam to Bangkok, a journey of nearly a thousand miles. In his interesting account of his journey, An Australian in China, published in 1895, while speaking well of the personalities of the many missionaries he met, he consistently belittled their success in obtaining converts. In after years he regretted this, as he felt he had given a wrong impression by not sufficiently stressing the value of their social and medical work. In February 1897 The Times appointed Morrison as the first permanent correspondent at Peking, and he took up his residence there in the following month. Unfortunately, his lack of knowledge in the Chinese language meant that he could not verify his stories and there is now much evidence to suggest that some of his reports contained both bias and deliberate lies against China.[1] There was much Russian activity in Manchuria at this time and in June Morrison went to Vladivostok. He travelled over a thousand miles to Stretensk and then across Manchuria to Vladivostok again. He reported to The Times that Russian engineers were making preliminary surveys from Kirin towards Port Arthur (Lüshunkou). On the very day his communication arrived in London, 6 March 1898, The Times received a telegram from Morrison to say that Russia had presented a five-day ultimatum to China demanding the right to construct a railway to Port Arthur. This was a triumph for The Times and its correspondent, but he had also shown prophetic insight in another phrase of his dispatch, when he stated that "the importance of Japan in relation to the future of Manchuria cannot be disregarded". Germany had occupied Kiao-chao towards the end of 1897, and a great struggle for political preponderacy was going on. Morrison in his telegrams showed "the prescience of a statesman and the accuracy of an historian" (The Times, 21 May 1920). In January 1899 he went to Siam and was able to point out that there was no need for French interference in that country, which was quite capable of governing itself. Later in the year he went to England, and early in 1900 paid a short visit to his relations in Australia. Returning to the east by way of Japan he then visited Korea before returning to Peking. The Boxer Uprising broke out soon after, and during the siege of the legations from June to August Morrison as an acting-lieutenant showed great courage, always ready to volunteer for every service of danger. He was superficially wounded in July[1] but was erroneously reported as killed. He was afterwards able to read his highly laudatory obituary notice, which occupied two columns of The Times on 17 July 1900. After a siege of 55 days, the legations were relieved on 14 August 1900 by an army of various nationalities under General Gaselee. The army then ransacked much of the palaces in Peking, with Morrison taking part in the looting, making off with silks, furs, porcelain and bronzes.[1] There was great uncertainty regarding the future of China in the following months, and through The Times Morrison managed to depict a skewed picture before the British public. While Russia and Japan united in opposing any dismemberment of China, the country was nevertheless punished by the imposition of a heavy indemnity. When the Russo-Japanese War broke out on 10 February 1904 Morrison became a correspondent with the Japanese army. He was present at the entry of the Japanese into Port Arthur (now Lüshunkou) early in 1905, and represented The Times at the Portsmouth, New Hampshire, U.S.A., peace conference. In 1907 he crossed China from Peking to the French border of Tonkin, and in 1910 rode from Honan across Asia to Andijan in Russian Turkestan, a journey of 3750 miles (6,000 km) which was completed in 175 days. From Andijan he took train to St Peterburg, and then travelled to London arriving on 29 July 1910. He returned to China and, when plague broke out in Manchuria, went to Harbin, where a great Chinese physician, Dr Wu Lien-teh, succeeded in staying the spread of a mortal sickness which seemed to threaten the whole world. Morrison did his part by publishing a series of articles advocating the launching of a modern scientific public health service in China. When the Chinese revolution began in 1911 Morrison took the side of the revolutionaries and the Chinese republic was established early in 1912. In August Morrison resigned his position on The Times to become political adviser to the Chinese government at a salary equivalent to £4000 a year, and immediately went to London to assist in floating a Chinese loan of £10,000,000. In China during the following years he had an anxious time advising, and endeavouring to deal with the political intrigues that were continually going on. He visited Australia again in December 1917 and returned to Peking in February 1918. He represented China during the peace discussions at Versailles in 1919, but his health began to give way and he retired to England well aware that he had only a short time to live. He died on 30 May, 1920 at Sidmouth, Devon and is buried there. Morrison had married in 1912 Jennie Wark Robin (1889-1923), his former secretary, who survived him for only three years. His three sons, Ian (1913-1950), Alastair Gwynne (1915-2009)[2], and Colin (1917-1990), all grew to manhood and graduated at the University of Cambridge.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

An Australian in ChinaBeing the Narrative of a Quiet Journey Across China to Burma

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

An Australian in China

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

1/5

This Elibron Classics book is a facsimile reprint of a 1902 edition by Horace Cox, London.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

An Australian in ChinaBeing the Narrative of a Quiet Journey Across China to Burma

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

An Australian in China

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

1/5

This Elibron Classics book is a facsimile reprint of a 1902 edition by Horace Cox, London.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Morrison George Ernest try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Morrison George Ernest try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!