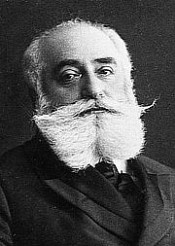

Nordau Max Simon

Max Simon Nordau (July 29, 1849 - January 23, 1923), born Simon Maximilian Südfeld in Pest, Hungary, was a Zionist leader, physician, author, and social critic. He was a co-founder of the World Zionist Organization together with Theodor Herzl, and president or vice president of several Zionist congresses. As a social critic, he wrote a number of controversial books, including The Conventional Lies of Our Civilisation (1883), Degeneration (1892), and Paradoxes (1896). Although not his most popular or successful work whilst alive, the book most often remembered and cited today is Degeneration. Nordau was born Simon Maximilian, or Simcha Südfeld on 29 July 1849 in Budapest, then part of the Austrian Empire. His father was Gabriel Südfeld, a Hebrew poet. His family were religious Orthodox Jews and he attended a Jewish elementary school, then a Catholic grammar school, before achieving a medical degree. He worked as a journalist for small newspapers in Budapest, before heading to Berlin in 1873, and changing his name. He soon moved to Paris as a correspondent for Die Neue Freie Presse and it was in Paris that he spent most of his life. Nordau was an example of a fully assimilated and acculturated European Jew. He was married to a Protestant Christian woman, despite his Hungarian background, he felt affiliated to German culture, writing in an autobiographical sketch, "When I reached the age of fifteen, I left the Jewish way of life and the study of the Torah... Judaism remained a mere memory and since then I have always felt as a German and as a German only." Nordau's conversion to Zionism was eventually triggered by the Dreyfus Affair. Many Jews, amongst them Theodor Herzl saw in the Dreyfus Affair evidence of the universality of Anti-Semitism. Nordau went on to play a major role in the World Zionist Organisation, indeed Nordau's relative fame certainly helped bring attention to the Zionist movement. He can be credited with giving the organisation a democratic character. Nordau's major work Entartung (Degeneration), is a moralistic attack on so-called degenerate art, as well as a polemic against the effects of a range of the rising social phenomena of the period, such as rapid urbanization and its perceived effects on the human body. Nordau's conversion to Zionism is in many ways typical of the rise of Zionism amongst Western European Jewry. The Dreyfus Affair beginning in 1893 was central to Nordau's conviction that Zionism was now necessary. Herzl's views were formed during his time in France where he recognised the universality of anti-Semitism; the Dreyfus Affair cemented his belief in the failure of assimilation. Nordau also witnessed the Paris mob outside the École Militaire crying "à morts les juifs!" His role of friend and advisor to Herzl, who was working as the correspondent for the Vienna Neue Freie Presse, began here in Paris. This trial went beyond a miscarriage of justice and in Herzl's words "contained the wish of the overwhelming majority in France, to damn a Jew, and in this one Jew, all Jews." Whether or not the anti-semitism manifested in France during the Dreyfus Affair was indicative of the majority of the French or simply a very vocal minority is open to debate. However the very fact that such sentiment had manifested itself in France was particularly significant. This was the country often seen as the model of the modern enlightened age, that had given the Europe the Great Revolution and consequently the Jewish Emancipation. Nordau's work as a critic of European civilisation and where it was heading certainly contributed to his eventual role in Zionism. One of the central tenets of Nordau's beliefs was evolution, in all things, and he concluded that Emancipation was not born out of evolution. French rationalism of the 18th century, based on pure logic, demanded that all men be treated equally. Nordau saw in Jewish Emancipation the result of 'a regular equation: Every man is born with certain rights; the Jews are human beings, consequently the Jews are born to own the rights of man.' This Emancipation was written in the statute books of Europe, but contrasted with popular social consciousness. It was this which explained the apparent contradiction of equality before the law, but the existence of anti-Semitism, and in particular 'racial' anti-Semitism, no longer based on old religious bigotry. Nordau cited England as an exception to this continental anti-Semitism that proved the rule. "In England, Emancipation is a truth…It had already been completed in the heart before legislation expressly confirmed it." Only if Emancipation came from changes within society, as opposed to abstract ideas imposed upon society, could it be a reality. This rejection of the accepted idea of Emancipation was not based entirely on the Dreyfus Affair. It had manifested itself much earlier in Die Konventionellen Lügen der Kulturmenschheit and runs through his denouncing of 'degenerate' and 'lunatic' anti-Semitism in Die Entartung. Nordau was central to the Zionist Congresses which played such a vital part in shaping what Zionism would become. Herzl had favoured the idea of a Jewish newspaper and an elitist "Society of Jews" to spread the ideas of Zionism. It was Nordau, convinced that Zionism had to at least appear democratic, despite the impossibility of representing all Jewish groups, who persuaded Herzl of the need for an assembly. This appearance of democracy certainly helped counter accusations that the "Zionists represented no one but themselves." There would be eleven such Congresses in all, the first, which Nordau organised, was in Basle, 29-31 August 1897. His fame as an intellectual helped draw attention to the project. Indeed the fact that Max Nordau, the trenchant essayist and journalist, was a Jew came as a revelation for many. Herzl obviously took centre stage, making the first speech at the Congress; Nordau followed him with an assessment of the Jewish condition in Europe. Nordau used statistics to paint a portrait of the dire straits of Eastern Jewry and also expressed his belief in the destiny of Jewish people as a democratic nation state, free of what he saw as the constraints of Emancipation. Nordau's speeches to the World Zionist Congress reexamined the Jewish people, in particular stereotypes of the Jews. He fought against the tradition of seeing the Jews as merchants or business people, arguing that most modern financial innovations such as insurance had been invented by gentiles. He saw the Jewish people as having a unique gift for politics, a calling which they were unable to fulfil without their own nation-state. Whereas Herzl favoured the idea of an elite forming policy, Nordau insisted the Congress have a democratic nature of some sort, calling for votes on key topics. Nordau was also a staunch eugenicist. [1] (in Future Human Evolution - page 85) As the 20th Century progressed, Nordau seemed increasingly irrelevant as a cultural critic. The rise of Modernism, the popularity of very different thinkers such as Friedrich Nietzsche, the huge technological changes and the devastation of the First World War, changed European society enormously. Even within the Zionist movement, other strains of thought were growing in popularity - influenced by Nietzsche, Socialism and other ideas. Nordau, in comparison, seemed very much a creature of the late 19th Century. Nordau died in Paris, France in 1923. In 1926 his remains were moved to Tel Aviv.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

the shackles of fate a play in five acts

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Purchase of this book includes free trial access to www.million-books.com where you can read more than a million books for free. This is an OCR edition with typos. Excerpt from book: SICKART. (Angrily.) Mother! (Turning to the others.) It is Mrs. Von Olderode. (To Mrs. Sickart.) Why do you not bring her in? j Mrs. Sickart. She will not come on account of the guests. Sickart. Really. Well, I will fetch her. (To the others.) You will permit me? (Goes quickly through door in background, followed by his mother, clumsily.) SCENE VI. Mr. Eckbaum, Mrs. Eckbaum, Voir Ewes. Mrs. Eckbaum. (Raising her hands in mock horror,) Oh! that woman! Eckbaum. (Smiling.) She is from the country, that is all. Mrs. Eckbaum. A little too much from the country. Almost, one would say, from the colonies, from Cameroon, or somewhere near. chapter{Section 4Von Ewes. I don't know, but somehow this old-fashioned person pleases me. And then she is so touching as a mother. Mrs. Eckbaum. That may be, but when I look at the woman I cannot get rid of the idea SCENE VII. The Same, Mrs. Vox Olderode, Sickart, Mrs. Sickart. Mrs. Von Olderode. (In dining-room.) Do let me take off my mantle at least. (Comes in. Mrs. Sickart and her son follow her. She remains standing, embarrassed, and bows. Mrs. Sickart bustles eagerly and fussily, pulls up an armchair, tries to take off her bonnet. Mrs. Von Olderode motions her off.) Sickart. (Presenting.) Mrs. Eckbanm, Mr. Von Ewes, Mrs. Von Olderode. Mr. Eckbaum you know already. Mrs. Von Oldbrodb. Pardon the disturbanceI did not wish to come in. Sickart. Here you are always welcome. Mrs. Von Olderode. But when you have welcome guests Mrs. Sickart. Dear madam, you are surely not going to say "Sie" to the boy! Mrs. Von Olderode. (Cautioning Jier laughingly.) Sh, sh. (To Eck'baum.) I am so thankful to you for all yon did in my lawsuit. Eckbaum. Oh, do not mention it,... --This text refers to the Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

the interpretation of history

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

This volume is produced from digital images created through the University of Michigan University Library's preservation reformatting program. The Library seeks to preserve the intellectual content of items in a manner that facilitates and promotes a variety of uses. The digital reformatting process results in an electronic version of the text that can both be accessed online and used to create new print copies. This book and thousands of others can be found in the digital collections of the University of Michigan Library. The University Library also understands and values the utility of print, and makes reprints available through its Scholarly Publishing Office.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

the conventional lies of our civilization

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Purchase of this book includes free trial access to www.million-books.com where you can read more than a million books for free. This is an OCR edition with typos. Excerpt from book: The Lie of a Monarchy and Aristocracy. If we were able to consider the existing institutions of our civilization from an artistic, esthetic point of view alone; if it were possible for us to study and criticise them 1with the abstract, impersonal interest of that Persian Prince Uzbek, described by Montesquieu, who travelled in foreign countries merely in search of amusement and shook their dust from his feet when he had left them behind him, we would not hesitate to accept the present arrangement of society as skillfully and consistently constructed, forming an harmonious whole. All the constituent parts are arranged in order, and are necessarily evolved from and dependent upon each other, ascending from the lowest to the highest, in an unbroken, logical sequence. When the grand gothic structure of mediasval state and society was erected, it presented an imposing appearance, and was regarded as a magnificent and comfortable place of refuge and safety by those whom it sheltered. Today only the ornamental fa9ade remains; the useful, habitable portions of the building have long since fallen into decay, so that any one seeking for shelter in it now, finds it impossible to discover a single nook or corner, in which he can be protected from the wind or rain. But the facade still retains its former beauty and grandeur, and arouses admiration in the beholder for the genius and skill of the architect. Nothing but one RELIGION INDISPENSABLE TO A MONARCHY. 71 wall is left standing today of what was once a fine and solid structure. But this wall is an architectural work of art in which all the details are skillfully and harmoniously subordinated to the general design. Of course we should not examine this architectural monument from the heap of ruins behind it; but if we approach it f...

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

on art and artists

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

This volume is produced from digital images created through the University of Michigan University Library's preservation reformatting program. The Library seeks to preserve the intellectual content of items in a manner that facilitates and promotes a variety of uses. The digital reformatting process results in an electronic version of the text that can both be accessed online and used to create new print copies. This book and thousands of others can be found in the digital collections of the University of Michigan Library. The University Library also understands and values the utility of print, and makes reprints available through its Scholarly Publishing Office.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

morals and the evolution of man

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Originally published in 1922. This volume from the Cornell University Library's print collections was scanned on an APT BookScan and converted to JPG 2000 format by Kirtas Technologies. All titles scanned cover to cover and pages may include marks notations and other marginalia present in the original volume.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

degeneration

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Purchase of this book includes free trial access to www.million-books.com where you can read more than a million books for free. This is an OCR edition with typos. Excerpt from book: .I courses music in a different key, and the jet gives out a different perfume. .jJThis idea of accompanying verses with odours was thrown outwears ago, half in jest, by Ernest Eckstein. ) Paris has carried it out in sacred earnest. The new school fetch the puppet theatre out of the nursery, and enact pieces for adults which, with artificial simplicity, pretend to hide or reveal a f profound meaning, and with great talent and ingenuity execute a magic-lantern of prettily drawn and painted figures moving across surprisingly luminous backgrounds; and these living pictures make visible the process of thought in the mind of the author who recites his accompanying poem, while a piano endeavours to illustrate the leading emotion. And to enjoy such exhibitions as these society crowds into a suburban circus, the loft of a back tenement, a second-hand costumier's shop, or a fantastic artist's restaurant, where the performances, in some room consecrated to beery potations, bring together the greasy habitue and the dainty aristocratic fledgling. CHAPTER III. DIAGNOSIS. The manifestations described in the preceding chapter must be patent enough to everyone, be he never so narrow a Philistine. The Philistine, however, regards them as a passing fashion and nothing more; for him the current terms, caprice, eccentricity, affectation of novelty, imitation, instinct, afford a sufficient explanation. The purely literary mind, whose merely aesthetic culture does not enable him to understand the con- nections of things, and to seize their real meaning, deceives himself and others as to his ignorance by means of sounding phrases, and loftily talks of a ' restless quest of a new ideal by the modern spirit,' ' the richer vibrations of the refined nervous system of the present day,' ' the ...

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a question of honor a tragedy of the present day

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

This volume is produced from digital images created through the University of Michigan University Library's preservation reformatting program. The Library seeks to preserve the intellectual content of items in a manner that facilitates and promotes a variety of uses. The digital reformatting process results in an electronic version of the text that can both be accessed online and used to create new print copies. This book and thousands of others can be found in the digital collections of the University of Michigan Library. The University Library also understands and values the utility of print, and makes reprints available through its Scholarly Publishing Office. --This text refers to an alternate Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Malady of the Century

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

1.5/5

Max Simon Nordau (1849-1923), born Simon Maximilian Südfeld, Südfeld Simon Miksa in Pest, Hungary, was a Zionist leader, physician, author, and social critic. He was a co-founder of the World Zionist Organization together with Theodor Herzl, and president or vice president of several Zionist congresses. As a social critic, he wrote a number of controversial books, including The Conventional Lies of Our Civilisation (1883), Degeneration (1892), and Paradoxes (1896). Although not his most popular or successful work whilst alive, the book most often remembered and cited today is Degeneration. Nordau's views were in many ways more like those of an 18th Century thinker, a belief in Reason, Progress, and more traditional, classical rules governing art and literature.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

How Women Love

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

A more unequally matched couple than the cartwright Molnar and his wife can seldom be seen.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Nordau Max Simon try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Nordau Max Simon try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!