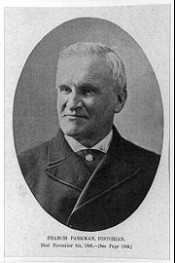

Parkman Francis

Francis Parkman (September 16, 1823 – November 8, 1893) was an American historian, best known as author of The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Rocky-Mountain Life and his monumental seven volume France and England in North America. These works are still valued as history and especially as literature, although the biases of his work have met with criticism. He was also a leading horticulturist, briefly a Professor of Horticulture at Harvard University and the first leader of the Arnold Arboretum, and author of several books on the topic. Parkman was born in Boston, Massachusetts to the Reverend Francis Parkman Sr. (1788-1852) and Caroline (Hall) Parkman. As a young boy, 'Frank' Parkman was found to be of poor health, and was sent to live with his maternal grandfather, who owned a 3000 acre (12 km²) tract of wilderness in nearby Medford, Massachusetts, in the hopes that a more rustic lifestyle would make him more sturdy. In the four years he stayed there, Parkman developed his love of the forests, which would animate his historical research. Indeed, he would later summarize his books as "the history of the American forest." He learned how to sleep and hunt, and could survive in the wilderness like a true pioneer. He later even learned to ride bareback, a skill that would come in handy when he found himself living with the Sioux. Parkman enrolled at Harvard College at age 16. In his second year he conceived the plan that would become his life's work. In 1843, at the age of 20, he traveled to Europe for eight months in the fashion of the Grand Tour. Parkman made expeditions through the Alps and the Apennine mountains, climbed Vesuvius, and even lived for a time in Rome, where he befriended Passionist monks who tried, unsuccessfully, to convert him to Catholicism. Upon graduation in 1845, he was persuaded to get a law degree, his father hoping such study would rid Parkman of his desire to write his history of the forests. It did no such thing, and after finishing law school Parkman proceeded to fulfill his great plan. His family was somewhat appalled at Parkman's choice of life work, since at the time writing histories of the American wilderness was considered ungentlemanly. Serious historians would study ancient history, or after the fashion of the time, the Spanish Empire. Parkman's works became so well-received that by the end of his lifetime histories of early America had become the fashion. Theodore Roosevelt dedicated his four-volume history of the frontier, The Winning of the West (1889-1896), to Parkman. In 1845, Parkman travelled west on a hunting expedition, where he spent a number of weeks living with the Sioux tribe, at a time when they were struggling with some of the effects of contact with Europeans, such as epidemic disease and alcoholism. This experience led Parkman to write about American Indians with a much different tone from earlier, more sympathetic portrayals represented by the "noble savage" stereotype. Writing in the era of Manifest Destiny, Parkman believed that the conquest and displacement of American Indians represented progress, a triumph of "civilization" over "savagery", a common view at the time.[1] A scion of a wealthy Boston family, Parkman had enough money to pursue his research without having to worry too much about finances. His financial stability was enhanced by his modest lifestyle, and later, by the royalties from his book sales. He was thus able to commit much of his time to research, as well as to travel. He travelled across North America, visiting most of the historical locations he wrote about, and made frequent trips to Europe seeking original documents with which to further his research. Parkman's accomplishments are all the more impressive in light of the fact that he suffered from a debilitating neurological illness, which plagued him his entire life, and which was never properly diagnosed. He was often unable to walk, and for long periods he was effectively blind, being unable to stand but the slightest amount of light. Much of his research involved having people read documents to him, and much of his writing was written in the dark, or dictated to others. Parkman married Catherine Scollay Bigelow on May 13, 1850; they had three children. A son died in childhood, and shortly afterwards, his wife died. He successfully raised two daughters, introducing them in to Boston society and seeing them both wed, with families of their own. Parkman died at age 70 in Jamaica Plain. He is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Parkman has been hailed as one of America's great historians and as a master of narrative history. His work has been praised by historians who have published essays in new editions of his work, including Pulitzer Prize winners C. Vann Woodward, Allan Nevins and Samuel Eliot Morison, along with Wilbur R. Jacobs, John Keegan, William Taylor, Mark Van Doren, David Levin, among others. Famous artists such as Thomas Hart Benton and Frederic Remington have illustrated Parkman's books. Numerous translations have spread the books around the world. Parkman's biases, particularly his attitudes about nationality, race, and especially Native Americans, have generated criticism. As C. Vann Woodward wrote in 1984: Too often Parkman could ignore evidence that was not in accord with his views, permit his bias to control his judgment, or sketch characterizations that are little better than hostile caricatures.... Modern sensibilities will be nettled by his casual stereotypes of national character and by the sharp distinction he draws between "civilization" and "savagery." Even more difficult to take is his portrayal (not always consistent or invariably negative) of the Indian as a beast of the forest, "man, wolf, and devil, all in one," and as a race inevitably and rightly doomed.[2] The English-born and Sorbonne-educated Canadian historian W. J. Eccles harshly criticized what he perceived as Parkman's bias against France and Roman Catholic policies, as well as what he considered Parkman's misuse of French language sources.[3] However, Parkman's most severe detractor was the American historian Francis Jennings, an outspoken and controversial critic of the European colonization of North America, who went so far as to characterize Parkman's work as "fiction" and Parkman himself as a "liar".[4] Unlike Jennings and Eccles, many modern historians have found much to praise in Parkman's work even while recognizing his limitations. Calling Jennings' critique "vitriolic and unfair," the historian Robert S. Allen has said that Parkman's history of France and England in North America "remains a rich mixture of history and literature which few contemporary scholars can hope to emulate".[5] The historian Michael N. McConnell, while acknowledging the historical errors and racial prejudice in Parkman's book The Conspiracy of Pontiac, has said: ...it would be easy to dismiss Pontiac as a curious—perhaps embarrassing—artifact of another time and place. Yet Parkman's work represents a pioneering effort; in several ways he anticipated the kind of frontier history now taken for granted.... Parkman's masterful and evocative use of language remains his most enduring and instructive legacy.[6] The American writer and literary critic Edmund Wilson (1894-1972) in his book O Canada (1965), described Parkman’s France and England in North America in these terms: “The clarity, the momentum and the color of the first volumes of Parkman’s narrative are among the most brilliant achievements of the writing of history as an art.” The Francis Parkman School in Forest Hills bears his name, as does Parkman Drive and the granite Francis Parkman Memorial at the site of his last home in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts. On September 16, 1967, the United States Post Office Department issued a 3¢ stamp honoring Parkman.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

The Conspiracy of Pontiac and the Indian War after the Conquest of Canada

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

A Half Century of Conflict - Volume IFrance and England in North America

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

The Conspiracy of Pontiac and the Indian War after the Conquest of Canada

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

A Half Century of Conflict - Volume IFrance and England in North America

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

la salle and the discovery of the great west france and england in north ameri

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

historic handbook of the northern tour lakes george and champlain niagara mon

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

an offering of sympathy to parents bereaved of their children and to others un

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Being A Collection From Manuscripts And Letters Not Before Published, With An Appendix Of Selections.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a survey of gods providence in the establishment of the churches of new england

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a record of the testimonial dinner to honorable joseph g cannon of illinois

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a half century of conflict france and england in north america part sixth vol

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a half century of conflict france and england in north america part sixth vo

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a half century of conflict volume 02

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

1/5

This book was converted from its physical edition to the digital format by a community of volunteers. You may find it for free on the web. Purchase of the Kindle edition includes wireless delivery.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Parkman Francis try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Parkman Francis try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!