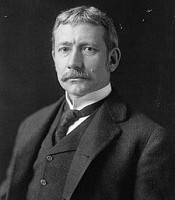

Root Elihu

Elihu Root (February 15, 1845 – February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer and statesman and the 1912 recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He was the prototype of the 20th century "wise man", who shuttled between high-level government positions in Washington, D.C. and private-sector legal practice in New York City. Root was born in Clinton, New York, to Oren Root and Nancy Whitney Buttrick. His father was professor of mathematics at Hamilton College, where Elihu attended college; there he joined the Sigma Phi Society, and was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa Society[1] After graduation, Root taught for one year at the Rome (N.Y.) Free Academy. In 1867, Root graduated from the New York University School of Law. He went into private practice as a lawyer. While mainly practicing corporate law, Root was a junior defense counsel during the corruption trial of William "Boss" Tweed. Root also had private clients including Jay Gould, Chester A. Arthur, Charles Anderson Dana, William C. Whitney, Thomas Fortune Ryan, and E. H. Harriman. Root was appointed U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York by President Chester A. Arthur. Root married Clara Frances Wales (died in 1928), who was the daughter of Salem Wales, the managing editor of Scientific American, in 1878. They had three children: Edith (married Ulysses S. Grant III), Elihu, Jr. (who became a lawyer), and Edward Wales (who became Professor of Art at Hamilton College). Root was a member of the Union League Club of New York and twice served as its president, 1898-99, and again from 1915-16. Root served as the United States Secretary of War 1899–1904 under William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. He reformed the organization of the United States Military. He was responsible for enlarging West Point and establishing the U.S. Army War College as well as the General Staff. He changed the procedures for promotions and organized schools for the special branches of the service. He also devised the principle of rotating officers from staff to line. Root was concerned about the new territories acquired after the Spanish-American War and worked out the procedures for turning Cuba over to the Cubans, wrote the charter of government for the Philippines, and eliminated tariffs on goods imported to the United States from Puerto Rico. Root left the cabinet in 1904 and returned to private practice as a lawyer. In 1905, President Roosevelt named Root to be the United States Secretary of State after the death of John Hay. As secretary, Root placed the consular service under the civil service. He maintained the Open Door Policy in the Far East. On a tour to Latin America in 1906, Root persuaded those governments to participate in the Hague Peace Conference. He worked with Japan in emigration to the United States and in dealings with China and established the Root-Takahira Agreement, which limited Japanese and American naval fortifications in the Pacific. He worked with Great Britain in resolving border disputes between the United States (Alaska) and Canada and also in the North Atlantic fisheries. He supported arbitration in resolving international disputes. Root served a term in the United States Senate as a Republican from New York from 1909 to 1915. He was an active member of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary. He chose not to seek reelection in 1914. During and after his Senate service, Root served as President of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace from 1910 to 1925. In a 1910 letter published by the New York Times, Root supported the proposed income tax amendment, which became the Sixteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution: It is said that a very large part of any income tax under the amendment would be paid by citizens of New York.... The reason why the citizens of New York will pay so large a part of the tax is New York City is the chief financial and commercial centre of a great country with vast resources and industrial activity. For many years Americans engaged in developing the wealth of all parts of the country have been going to New York to secure capital and market their securities and to buy their supplies. Thousands of men who have amassed fortunes in all sorts of enterprises in other states have gone to New York to live because they like the life of the city or because their distant enterprises require representation at the financial centre. The incomes of New York are in a great measure derived from the country at large. A continual stream of wealth sets toward the great city from the mines and manufactories and railroads outside of New York.[2] In 1912, as a result of his work to bring nations together through arbitration and cooperation, Root received the Nobel Peace Prize. At the outbreak of World War I, Root opposed President Woodrow Wilson's policy of neutrality. He did support Wilson once the United States entered the war. In June 1916, Root was drafted for the Republican presidential nomination but declined, stating that he was too old to bear the burden of the Presidency.[3] At the Republican National Convention, Root reached his peak strength of 103 votes on the first ballot. The Republican presidential nomination went to Charles Evans Hughes, who lost the election to Democrat Woodrow Wilson. In June 1917, at age 72, he was sent to Russia by President Wilson to arrange American co-operation with the new revolutionary government. The AFL's James Duncan, socialist Charles Edward Russell, general Hugh L. Scott, admiral James H. Glennon, New York banker S.R. Bertron, John Mott and Charles Richard Crane were members of Root's mission. They traveled from Vladivostok across Siberia in the Czar's former train. Root remained in Petrograd for close to a month, and was not much impressed by what he saw. The Russians, he said, "are sincerely, kindly, good people but confused and dazed." He summed up his attitude to the Provisional Government very trenchantly: "No fight, no loans," which referred to the current conflict with Germany in World War I. After World War I, Root supported the League of Nations and served on the commission of jurists, which created the Permanent Court of International Justice. In 1922, President Warren G. Harding appointed him as a delegate to the International Conference on the Limitation of Armaments. He was the founding chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations, established in 1921 in New York. Root worked with Andrew Carnegie in programs for international peace and the advancement of science. He was the first president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He helped found the American Society of International Law in 1906. He was among the founders of the American Law Institute in 1923. Furthermore, he also helped create the Hague Academy of International Law in the Netherlands. Root also served as vice president of the American Peace Society, which publishes World Affairs, the oldest U.S. journal on international relations. In addition to the Nobel Prize, Root was awarded the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Crown (from Belgium) and the Grand Commander of the Order of George I (from Greece). He was the second cousin twice removed of Henry Luce, through Elihu Root (1772-1843). Before his death, Root had been the last surviving member of the McKinley Cabinet. Root died in 1937 in New York City, with his family by his side. He is buried at the Hamilton College Cemetery.[4] His home that he purchased in 1893, the Elihu Root House, was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1972. Henry Dunant/Frédéric Passy (1901) · Élie Ducommun/Charles Gobat (1902) · William Cremer (1903) · Institut de Droit International (1904) · Bertha von Suttner (1905) · Theodore Roosevelt (1906) · Ernesto Moneta/Louis Renault (1907) · Klas Arnoldson/Fredrik Bajer (1908) · A.M.F. Beernaert/Paul Estournelles de Constant (1909) · International Peace Bureau (1910) · Tobias Asser/Alfred Fried (1911) · Elihu Root (1912) · Henri La Fontaine (1913) · International Committee of the Red Cross (1917) · Woodrow Wilson (1919) · Léon Bourgeois (1920) · Hjalmar Branting/Christian Lange (1921) · Fridtjof Nansen (1922) · Austen Chamberlain/Charles Dawes (1925)

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

Latin America and the United StatesAddresses by Elihu Root

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Experiments in Government and the Essentials of the Constitution

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

This volume is produced from digital images created through the University of Michigan University Library's preservation reformatting program. The Library seeks to preserve the intellectual content of items in a manner that facilitates and promotes a variety of uses. The digital reformatting process results in an electronic version of the text that can both be accessed online and used to create new print copies. This book and thousands of others can be found in the digital collections of the University of Michigan Library. The University Library also understands and values the utility of print, and makes reprints available through its Scholarly Publishing Office.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Latin America and the United States

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Purchase of this book includes free trial access to www.million-books.com where you can read more than a million books for free. This is an OCR edition with typos. Excerpt from book: today's date to give to this edifice in which the International Pan American Conference is now in session the name of Palacio Monroe. [The Conference then adjourned.] BANQUET OF THE MINISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS Speech Of His Excellency Baron Do Rio Branco Minister For Foreign Affairs Rio de Janeiro, July 28, 1906 The enthusiastic and cordial welcome you have received in Brazil must certainly have convinced you that this country is a true friend of yours. This friendship is of long standing. It dates from the first days of our independence, which the Government of the United States was the first to recognize, as the Government of Brazil was the first to applaud the terms and spirit of the declarations contained in the famous message of President Monroe. Time has but increased, in the minds and hearts of successive generations of Brazilians, the sympathy and admiration which the founders of our nationality felt for the United States of America. The manifestations of friendship for the United States which you have witnessed come from all the Brazilian people, and not from the official world alone, and it is our earnest desire that this friendship, which has never been disturbed in the past, may continue forever and grow constantly closer and stronger. Gentlemen, I drink to the health of the distinguished Secretary of State of the United States of America, Mr. Elihu Root, who has so brilliantly and effectively aided President Roosevelt in the great work of the political rapprockfmeni of the American nations. Reply Of Mr. Root I Thank you again and still again for the generous hospitality which is making my reception in Brazil so charming. Coming here as head of the department of foreign affairs of my country and seated at the table of the minister of ...

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

Latin America and the United StatesAddresses by Elihu Root

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Experiments in Government and the Essentials of the Constitution

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

This volume is produced from digital images created through the University of Michigan University Library's preservation reformatting program. The Library seeks to preserve the intellectual content of items in a manner that facilitates and promotes a variety of uses. The digital reformatting process results in an electronic version of the text that can both be accessed online and used to create new print copies. This book and thousands of others can be found in the digital collections of the University of Michigan Library. The University Library also understands and values the utility of print, and makes reprints available through its Scholarly Publishing Office.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Latin America and the United States

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Purchase of this book includes free trial access to www.million-books.com where you can read more than a million books for free. This is an OCR edition with typos. Excerpt from book: today's date to give to this edifice in which the International Pan American Conference is now in session the name of Palacio Monroe. [The Conference then adjourned.] BANQUET OF THE MINISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS Speech Of His Excellency Baron Do Rio Branco Minister For Foreign Affairs Rio de Janeiro, July 28, 1906 The enthusiastic and cordial welcome you have received in Brazil must certainly have convinced you that this country is a true friend of yours. This friendship is of long standing. It dates from the first days of our independence, which the Government of the United States was the first to recognize, as the Government of Brazil was the first to applaud the terms and spirit of the declarations contained in the famous message of President Monroe. Time has but increased, in the minds and hearts of successive generations of Brazilians, the sympathy and admiration which the founders of our nationality felt for the United States of America. The manifestations of friendship for the United States which you have witnessed come from all the Brazilian people, and not from the official world alone, and it is our earnest desire that this friendship, which has never been disturbed in the past, may continue forever and grow constantly closer and stronger. Gentlemen, I drink to the health of the distinguished Secretary of State of the United States of America, Mr. Elihu Root, who has so brilliantly and effectively aided President Roosevelt in the great work of the political rapprockfmeni of the American nations. Reply Of Mr. Root I Thank you again and still again for the generous hospitality which is making my reception in Brazil so charming. Coming here as head of the department of foreign affairs of my country and seated at the table of the minister of ...

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Root Elihu try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Root Elihu try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!