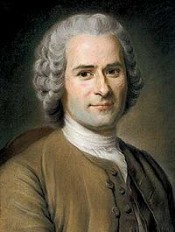

Rousseau Jean-Jacques

Jean Jacques Rousseau (Geneva, 28 June 1712 – Ermenonville, 2 July 1778) was a major French philosopher, writer, and composer of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, whose political philosophy influenced the French Revolution and the development of modern political and educational thought. His novel, Emile: or, On Education, which he considered his most important work, is a seminal treatise on the education of the whole person for citizenship. His sentimental novel, Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse, was of great importance to the development of pre-Romanticism[1] and romanticism in fiction.[2] Rousseau's autobiographical writings: his Confessions, which initiated the modern autobiography, and his Reveries of a Solitary Walker (along with the works of Lessing and Goethe in Germany, and Richardson and Sterne in England), were among the pre-eminent examples of the late eighteenth-century movement known as the "Age of Sensibility", featuring an increasing focus on subjectivity and introspection that has characterized the modern age. Rousseau also wrote a play and two operas, and made important contributions to music as a theorist. During the period of the French Revolution, Rousseau was the most popular of the philosophes among members of the Jacobin Club. He was interred as a national hero in the Panthéon in Paris, in 1794, sixteen years after his death. Rousseau was born in 1712 in Geneva, since 1536 a Huguenot republic and the seat of Calvinism (now part of Switzerland). Rousseau was proud that his family, of the moyen (or middle-class) order, had voting rights in that city and throughout his life he described himself as a citizen of Geneva. In theory Geneva was governed democratically by its male voting citizens (who were a minority of the population). In fact, a secretive executive committee, called the Little Council (made up of 25 members of its wealthiest families), ruled the city. In 1707 a patriot called Pierre Fatio protested at this situation and the Little Council had him shot. Jean-Jacques Rousseau's father Isaac was not in the city at this time, but Jean-Jacques's grandfather supported Fatio and was penalized for it.[3] Rousseau's father, Isaac Rousseau, was a watchmaker who, notwithstanding his artisan status, was well educated and a lover of music. "A Genevan watchmaker," Rousseau wrote, "is a man who can be introduced anywhere; a Parisian watchmaker is only fit to talk about watches."[4] Rousseau's mother, Suzanne Bernard Rousseau, the daughter of a Calvinist preacher, died of birth complications nine days after his birth. He and his older brother François were brought up by their father and a paternal aunt, also named Suzanne. Rousseau had no recollection of learning to read, but he remembered how when he was five or six his father encouraged his love of reading: Every night, after supper, we read some part of a small collection of romances [i.e., adventure stories], which had been my mother's. My father's design was only to improve me in reading, and he thought these entertaining works were calculated to give me a fondness for it; but we soon found ourselves so interested in the adventures they contained, that we alternately read whole nights together and could not bear to give over until at the conclusion of a volume. Sometimes, in the morning, on hearing the swallows at our window, my father, quite ashamed of this weakness, would cry, "Come, come, let us go to bed; I am more a child than thou art." —Confessions, Book 1 Not long afterward, Rousseau abandoned his taste for escapist stories in favor of the antiquity of Plutarch's Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans, which he would read to his father while he made watches. When Rousseau was ten, his father, an avid hunter, got into a legal quarrel with a wealthy landowner on whose lands he had been caught trespassing. To avoid certain defeat in the courts, he moved away to Nyon in the territory of Bern, taking Rousseau's aunt Suzanne with him. He remarried, and from that point Jean-Jacques saw little of him.[5] Jean-Jacques was left with his maternal uncle, who packed him, along with his own son, Abraham Bernard, away to board for two years with a Calvinist minister in a hamlet outside of Geneva. Here the boys picked up the elements of mathematics and drawing. Rousseau, who was always deeply moved by religious services, for a time even dreamed of becoming a Protestant minister. Virtually all our information about Rousseau's first youth has come from his posthumously published Confessions, in which the chronology is somewhat confused, though recent scholars have combed the archives for confirming evidence to fill in the blanks. At age 13 Rousseau was apprenticed first to a notary and then to an engraver who beat him. At fifteen he ran away from Geneva (on 14 March 1728) after returning to the city and finding the city gates locked due to the curfew. In adjoining Savoy he took shelter with a Roman Catholic priest, who introduced him to Françoise-Louise de Warens, age 29. She was a noblewoman of Protestant background who was separated from her husband. As professional lay proselytizer, she was paid by the King of Piedmont to help bring Protestants to Catholicism. They sent the boy to Turin, the capital of Savoy (which included Piedmont, in what is now Italy), to complete his conversion. This resulted in his having to give up his Genevan citizenship, although he would later revert to Calvinism in order to regain it. In converting to Catholicism, both De Warens and Rousseau were likely reacting to the severity of Calvinism's insistence on the total depravity of man. Leo Damrosch writes, "an eighteenth-century Genevan liturgy still required believers to declare ‘that we are miserable sinners, born in corruption, inclined to evil, incapable by ourselves of doing good'."[6] De Warens, a deist by inclination, was attracted to Catholicism's doctrine of forgiveness of sins. Finding himself on his own, since his father and uncle had more or less disowned him, the teenage Rousseau supported himself for a time as a servant, secretary, and tutor, wandering in Italy (Piedmont and Savoy) and France. During this time, he lived on and off with De Warens, whom he idolized and called his "maman". Flattered by his devotion, De Warens tried to get him started in a profession, and arranged formal music lessons for him. At one point, he briefly attended a seminary with the idea of becoming a priest. When Rousseau reached twenty De Warens took him as her lover, whilst intimate also with the steward of her house. The sexual aspect of their relationship (in fact a ménage à trois) confused Rousseau and made him uncomfortable, but he always considered De Warens the greatest love of his life. A rather profligate spender, she had a large library and loved to entertain and listen to music. She and her circle, comprising educated members of the Catholic clergy, introduced Rousseau to the world of letters and ideas. Rousseau had been an indifferent student, but during his twenties, which were marked by long bouts of hypochondria, he applied himself in earnest to the study of philosophy, mathematics, and music. At twenty-five, he came into a small inheritance from his mother and used a portion of it to repay De Warens for her financial support of him. At twenty-seven he took a job as a tutor in Lyon. In 1742 Rousseau moved to Paris in order to present the Académie des Sciences with a new system of numbered musical notation he believed would make his fortune. His system, intended to be compatible with typography, is based on a single line, displaying numbers representing intervals between notes and dots and commas indicating rhythmic values. Believing the system was impractical, the Academy rejected it, though they praised his mastery of the subject, and urged him to try again. From 1743 to 1744 Rousseau had an honorable but ill-paying post as a secretary to the Comte de Montaigue, the French ambassador to Venice. This awoke in him a life-long love for Italian music, particularly opera: I had brought with me from Paris the prejudice of that city against Italian music; but I had also received from nature a sensibility and niceness of distinction which prejudice cannot withstand. I soon contracted that passion for Italian music with which it inspires all those who are capable of feeling its excellence. In listening to barcaroles, I found I had not yet known what singing was... —Confessions Rousseau's employer routinely received his stipend as much as a year late and paid his staff irregularly.[7] After eleven months Rousseau quit, taking from the experience a profound distrust of government bureaucracy. Returning to Paris, the penniless Rousseau befriended and became the lover of Thérèse Levasseur, a pretty seamstress who was the sole support of her termagant mother and numerous ne'er-do-well siblings. At first they did not live together, though later Rousseau took Thérèse and her mother in to live with him as his servants, and himself assumed the burden of supporting her large family. According to his Confessions, before she moved in with him, Thérèse bore him a son and as many as four other children (there is no independent for this number[8]). Rousseau wrote that he persuaded Thérèse to give each of the newborns up to a foundling hospital, for the sake of her "honor". "Her mother, who feared the inconvenience of a brat, came to my aid, and she [Thérèse] allowed herself to be overcome" (Confessions). The foundling hospitals had been started as a reform to save the numerous infants who were being abandoned in the streets of Paris. Infant mortality at that date was extremely high — some fifty percent, in large part because families sent their infants to be wet nursed. The mortality rate in the foundling hospitals, which also sent the babies out to be wet nursed, proved worse, however, and most of the infants sent there likely perished. Ten years later Rousseau made inquiries about the fate of his son, but no record could be found. When Rousseau subsequently became celebrated as a theorist of education and child-rearing, his abandonment of his children was used by his critics, including Voltaire and Edmund Burke, as the basis for ad hominem attacks. In an irony of fate, Rousseau's later injunction to women to breastfeed their own babies (as had previously been recommended by the French natural scientist Buffon), probably saved the lives of thousands of infants.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

Widger's Quotations from Project Gutenberg Edition of Confessions of J. J. Rousseau

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Quotes and Images From The Confessions of J. J. Rousseau

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

1/5

This book is devoted to the life of work of an outstanding French thinker, philosopher and writer J. J. Rousseau. Here readers will find his quotes and images. The book is definitely recommended for everyone who is interested in the great personality of Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

Widger's Quotations from Project Gutenberg Edition of Confessions of J. J. Rousseau

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Quotes and Images From The Confessions of J. J. Rousseau

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

1/5

This book is devoted to the life of work of an outstanding French thinker, philosopher and writer J. J. Rousseau. Here readers will find his quotes and images. The book is definitely recommended for everyone who is interested in the great personality of Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

A Discourse Upon the Origin and the Foundation Of

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

This book was converted from its physical edition to the digital format by a community of volunteers. You may find it for free on the web. Purchase of the Kindle edition includes wireless delivery.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Confessions of J. J. Rousseau — Volume 11

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Confessions of J. J. Rousseau — Volume 10

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Confessions of J. J. Rousseau — Volume 09

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Confessions of J. J. Rousseau — Volume 08

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Confessions of J. J. Rousseau — Volume 04

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Confessions of J. J. Rousseau — Volume 03

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Confessions of J. J. Rousseau — Volume 01

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Rousseau Jean-Jacques try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Rousseau Jean-Jacques try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!