Sassoon Siegfried

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon, CBE, MC (8 September 1886 – 1 September 1967) was an English poet and author. He became known as a writer of satirical anti-war verse during World War I. He later won acclaim for his prose work, notably his three-volume fictionalised autobiography, collectively known as the "Sherston Trilogy". Siegfried Sassoon was born at Weirleigh hospital (which still stands) in Matfield, Kent, to a Jewish father and an Anglo-Catholic mother. His father, Alfred Ezra Sassoon (1861-1895) (son of Sassoon David Sassoon), came from the wealthy Indian Baghdadi Jewish Sassoon merchant family but was disinherited for marrying outside the faith. His mother, Theresa, belonged to the Thornycroft family, sculptors responsible for many of the best-known statues in London—her brother was Sir Hamo Thornycroft. There was no German ancestry in Sassoon's family; he owed his unusual first name to his mother's predilection for the operas of Wagner. His middle name was taken from the surname of a clergyman with whom she was friendly. He was the second of three sons, the others being Michael and Hamo (named after his uncle). When Sassoon was four years old, his parents split up. His father would visit the boys weekly at their family home, but Theresa would lock herself in the drawing room, still deeply upset by the situation. In 1894 Alfred Sassoon died of tuberculosis, leaving Sassoon devastated. Sassoon was educated at The New Beacon Preparatory School, Kent, Marlborough College in Wiltshire (at Cotton House, Marlborough College), and at Clare College, Cambridge, (of which he was made an honorary fellow in 1953) where he studied both law and history from 1905 to 1907. However, he dropped out of university without a degree and spent the next few years hunting, playing cricket and privately publishing a few volumes of not very highly acclaimed poetry. His income was just enough to prevent his having to seek work, but not enough to live extravagantly. His first real success was The Daffodil Murderer, a parody of The Everlasting Mercy by John Masefield, published in 1913 under the pseudonym of "Saul Kain". Motivated by patriotism, Sassoon joined the military just as the threat of World War I was realised and was in service with the Sussex Yeomanry on the day the United Kingdom declared war (4 August 1914). He broke his arm badly in a riding accident and was put out of action before even leaving England, spending the spring of 1915 convalescing. At around this time his younger brother Hamo was killed in the Gallipoli Campaign[1] (Rupert Brooke, whom Siegfried had briefly met, died on the way there); Hamo's death hit Siegfried very hard. He was commissioned into 3rd Battalion (Special Reserve), Royal Welch Fusiliers as a second lieutenant on 29 May 1915,[2] and in November, he was sent to the 1st Battalion in France. He was thus brought into contact with Robert Graves and they became close friends. United by their poetic vocation, they often read and discussed one another's work. Though this did not have much perceptible influence on Graves's poetry, his views on what may be called 'gritty realism' profoundly affected Sassoon's concept of what constituted poetry. He soon became horrified by the realities of war, and the tone of his writing changed completely: where his early poems exhibit a Romantic dilettantish sweetness, his war poetry moves to an increasingly discordant music, intended to convey the ugly truths of the trenches to an audience hitherto lulled by patriotic propaganda. Details such as rotting corpses, mangled limbs, filth, cowardice and suicide are all trademarks of his work at this time, and this philosophy of 'no truth unfitting' had a significant effect on the movement towards Modernist poetry. Sassoon's periods of duty on the Western Front were marked by exceptionally brave actions, including the single-handed capture of a German trench in the Hindenburg Line. He often went out on night-raids and bombing patrols and demonstrated ruthless efficiency as a company commander. Deepening depression at the horror and misery the soldiers were forced to endure produced in Sassoon a paradoxically manic courage, and he was nicknamed "Mad Jack" by his men for his near-suicidal exploits. On 27 July 1916 he was awarded the Military Cross; the citation read: For conspicuous gallantry during a raid on the enemy's trenches. He remained for 1½ hours under rifle and bomb fire collecting and bringing in our wounded. Owing to his courage and determination all the killed and wounded were brought in.[3] He was also (unsuccessfully) recommended for the Victoria Cross for the capture of the German trench.[4] Despite his decoration and reputation, he decided in 1917 to make a stand against the conduct of the war. One of the reasons for his violent anti-war feeling was the death of his friend, David Cuthbert Thomas (called "Dick Tiltwood" in the Sherston trilogy). He would spend years trying to overcome his grief. He published a famous piece called "The Soldier's Declaration," speaking out against the futility of the war for himself and his fellow soldiers, stating: "I am making this statement as an act of willful defiance of military authority, because I believe that the war is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it." [5]}} At the end of a spell of convalescent leave, Sassoon declined to return to duty; instead, encouraged by pacifist friends such as Bertrand Russell and Lady Ottoline Morrell, he sent a letter to his commanding officer titled A Soldier’s Declaration, which was forwarded to the press and read out in Parliament by a sympathetic MP. Rather than court-martial Sassoon, the Under-Secretary of State for War, Ian Macpherson decided that he was unfit for service and had him sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital near Edinburgh, where he was officially treated for neurasthenia ("shell shock").[4] Before declining to return to service he had thrown the ribbon from his Military Cross into the river Mersey. The novel Regeneration, by Pat Barker, is a fictionalised account of this period in Sassoon's life, and was made into a film starring James Wilby as Sassoon and Jonathan Pryce as W. H. R. Rivers, the psychiatrist responsible for Sassoon's treatment. Rivers became a kind of surrogate father to the troubled young man, and his sudden death in 1922 was a major blow to Sassoon. At Craiglockhart, Sassoon met Wilfred Owen, another poet who would eventually exceed him in fame. It was thanks to Sassoon that Owen persevered in his ambition to write better poetry. A manuscript copy of Owen's Anthem for Doomed Youth containing Sassoon's handwritten amendments survives as testimony to the extent of his influence and is currently on display at London's Imperial War Museum. To all intents and purposes, Sassoon became to Owen "Keats and Christ and Elijah"; surviving documents demonstrate clearly the depth of Owen's love and admiration for him. Both men returned to active service in France, but Owen was killed in 1918. Sassoon, despite all this was promoted to lieutenant, and having spent some time out of danger in Palestine, eventually returned to the Front and was almost immediately wounded again—by friendly fire, but this time in the head—and spent the remainder of the war in Britain. By this time he had been promoted acting captain, he relinquished his commission on health grounds on 12 March 1919, and was allowed to retain the rank of captain.[6] After the war, Sassoon was instrumental in bringing Owen's work to the attention of a wider audience. Their friendship is the subject of Stephen MacDonald's play, Not About Heroes. The war had brought Sassoon into contact with men from less advantaged backgrounds, and he had developed Socialist sympathies. Having lived for a period at Oxford, where he spent more time visiting literary friends than studying, he dabbled briefly in the politics of the Labour movement, and in 1919 took up a post as literary editor of the socialist Daily Herald. During his period at the Herald, Sassoon was responsible for employing several eminent names as reviewers, including E. M. Forster and Charlotte Mew, and commissioned original material from "names" like Arnold Bennett and Osbert Sitwell. His artistic interests extended to music. While at Oxford he was introduced to the young William Walton, whose friend and patron he became. Walton later dedicated his Portsmouth Point overture to Sassoon in recognition of his financial assistance and moral support. Sassoon later embarked on a lecture tour of the USA, as well as travelling in Europe and throughout Britain. He acquired a car, a gift from the publisher Frankie Schuster, and became renowned among his friends for his lack of driving skill, but this did not prevent him making full use of the mobility it gave him. Meanwhile, he was beginning to practise his homosexuality more openly, embarking on an affair with artist Gabriel Atkin, to whom he had been introduced by mutual friends. During his US tour, he met a young actor who treated him callously. Nevertheless, he was adored by female audiences, including one at Vassar College. Sassoon was a great admirer of the Welsh poet Henry Vaughan. On a visit to Wales in 1923, he paid a pilgrimage to Vaughan's grave at Llansanffraid, Powys, and there wrote one of his best-known peacetime poems, At the Grave of Henry Vaughan. The deaths of three of his closest friends, Edmund Gosse, Thomas Hardy and Frankie Schuster (the publisher), within a short space of time, came as another serious setback to his personal happiness. At the same time, Sassoon was preparing to take a new direction. While in America, he had experimented with a novel. In 1928, he branched out into prose, with Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man, the anonymously-published first volume of a fictionalised autobiography, which was almost immediately accepted as a classic, bringing its author new fame as a humorous writer. The book won the 1928 James Tait Black Award for fiction. Sassoon followed it with Memoirs of an Infantry Officer (1930) and Sherston's Progress (1936). In later years, he revisited his youth and early manhood with three volumes of genuine autobiography, which were also widely acclaimed. These were The Old Century, The Weald of Youth and Siegfried's Journey.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

the old huntsman and other poems

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

1918. A collection of verse from the English novelist and poet who, after serving as an officer in World War I, expressed his conviction of the brutality and waste of war in his grim, forceful, realistic verse.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

picture show

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Originally published in 1911. This volume from the Cornell University Library's print collections was scanned on an APT BookScan and converted to JPG 2000 format by Kirtas Technologies. All titles scanned cover to cover and pages may include marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

the old huntsman and other poems

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

1918. A collection of verse from the English novelist and poet who, after serving as an officer in World War I, expressed his conviction of the brutality and waste of war in his grim, forceful, realistic verse.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

picture show

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Originally published in 1911. This volume from the Cornell University Library's print collections was scanned on an APT BookScan and converted to JPG 2000 format by Kirtas Technologies. All titles scanned cover to cover and pages may include marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The War Poems of Siegfried Sassoon

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Siegfried Sassoon was a wonderful poet and writer, he created many masterpieces… but it was Great War with it horrors and pains that arose in him his great and unique talent, made him write his best things and gave him world fame… If you hold this book, you will soon read his best poems and enjoy many beautiful moments.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

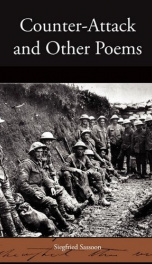

Counter-Attack and Other Poems

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Siegfried Sassoon was an English poet and author. He became known as a writer of satirical anti-war verse during World War I. His first success was The Daffodil Murderer, a parody of The Everlasting Mercy by John Masefield, published in 1913. Sassoon joined the military in 1914, but a badly broken arm kept him in England. At about this time his brother Hamo was killed in action. His strong poetry conveys the ugly truth of the soldiers in the trenches. He believed in the philosophy of "No truth unfitting" as seen in his images of rotting corpses, mangled limbs, filth, cowardice and suicide.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

- Professional & Technical / Engineering / Industrial, Manufacturing & Operational Systems / Manufacturing

- Books / History / Europe / Malta

- Nonfiction / Education / Education Theory / History

- Literature & Fiction / Drama / British & Irish

- Biographies & Memoirs / Historical / British

- Literature & Fiction / Authors, A-Z / (S)

if you like Sassoon Siegfried try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

- Professional & Technical / Engineering / Industrial, Manufacturing & Operational Systems / Manufacturing

- Books / History / Europe / Malta

- Nonfiction / Education / Education Theory / History

- Literature & Fiction / Drama / British & Irish

- Biographies & Memoirs / Historical / British

- Literature & Fiction / Authors, A-Z / (S)

if you like Sassoon Siegfried try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!