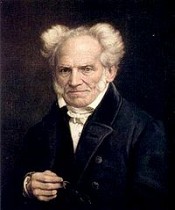

Schopenhauer Arthur

Arthur Schopenhauer (22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher known for his atheistic pessimism and philosophical clarity. At age 25, he published his doctoral dissertation, On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason, which examined the fundamental question of whether reason alone can unlock answers about the world. Schopenhauer's most influential work, The World as Will and Representation, emphasized the role of man's basic motivation, which Schopenhauer called will. His analysis of will led him to the conclusion that emotional, physical, and sexual desires can never be fulfilled. Consequently, he favored a lifestyle of negating human desires, similar to the teachings of Buddhism and Vedanta. Schopenhauer's metaphysical analysis of will, his views on human motivation and desire, and his aphoristic writing style influenced many well-known thinkers including Friedrich Nietzsche,[1] Richard Wagner, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Erwin Schrödinger, Albert Einstein,[2] and Sigmund Freud. Arthur Schopenhauer was born in the city of Danzig (Gdańsk) as the son of Heinrich Floris Schopenhauer and Johanna Trosiener,[3] both descendants of wealthy German Patrician families. When the Kingdom of Prussia acquired the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth city of Danzig in 1793, Schopenhauer's family moved to Hamburg. In 1805, Schopenhauer's father committed suicide.[4] Schopenhauer's mother Johanna shortly after moved to Weimar, then the centre of German literature, to pursue her writing career. After one year, Schopenhauer left the family business in Hamburg to join her. Schopenhauer became a student at the University of Göttingen in 1809. There he studied metaphysics and psychology under Gottlob Ernst Schulze, the author of Aenesidemus, who advised him to concentrate on Plato and Kant. In Berlin, from 1811 to 1812, he had attended lectures by the prominent post-Kantian philosopher J. G. Fichte and the theologian Schleiermacher. In 1814, Schopenhauer began his seminal work The World as Will and Representation (Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung). He would finish it in 1818 and publish it the following year. In Dresden in 1819, Schopenhauer fathered an illegitimate child who was born and died the same year.[5][6] In 1820, Schopenhauer became a lecturer at the University of Berlin. He scheduled his lectures to coincide with those of the famous philosopher G. W. F. Hegel, whom Schopenhauer described as a "clumsy charlatan".[7] However, only five students turned up to Schopenhauer's lectures, and he dropped out of academia. A late essay, "On University Philosophy", expressed his resentment towards university philosophy. In 1831, a cholera epidemic broke out in Berlin and Schopenhauer left the city. Schopenhauer settled permanently in Frankfurt in 1833, where he remained for the next twenty-seven years, living alone except for a succession of pet poodles named Atma and Butz. Schopenhauer had a robust constitution, but in 1860 his health began to deteriorate. He died of heart failure on 21 September 1860, while sitting in his armchair at home. He was 72. While in Berlin, Schopenhauer was named as a defendant in an action at law initiated by a woman named Caroline Marquet.[1] She asked for damages, alleging that Schopenhauer had pushed her. Knowing that he was a man of some means and that he disliked noise, she deliberately annoyed him by raising her voice while standing right outside his door. Marquet alleged that the philosopher had assaulted and battered her after she refused to leave his doorway. Her companion testified that she saw Marquet prostrate outside his apartment. Because Marquet won the lawsuit, he made payments to her for the next twenty years.[8] When she died, he wrote on a copy of her death certificate, Obit anus, abit onus ("The old woman dies, the burden is lifted").[9] A key focus of Schopenhauer was his investigation of individual motivation. Before Schopenhauer, Hegel had popularized the concept of Zeitgeist, the idea that society consisted of a collective consciousness which moved in a distinct direction, dictating the actions of its members. Schopenhauer, a reader of both Kant and Hegel, criticized their logical optimism and the belief that individual morality could be determined by society and reason. Schopenhauer believed that humans were motivated only by their own basic desires, or Wille zum Leben (Will to Live), which directed all of mankind.[10] For Schopenhauer, human desire was futile, illogical, directionless, and, by extension, so was all human action in the world. To Schopenhauer, the Will is a metaphysical existence which controls not only the actions of individual, intelligent agents, but ultimately all observable phenomena. Will, for Schopenhauer, is what Kant called the "thing-in-itself". For Schopenhauer, human desiring, "willing," and craving cause suffering or pain. A temporary way to escape this pain is through aesthetic contemplation (a method comparable to Zapffe's "Sublimation"). This is the next best way, short of not willing at all, which is the best way. Total absorption in the world as representation prevents a person from suffering the world as will. Art diverts the spectator's attention from the grave everyday world and lifts him or her into a world that consists of mere play of images. With music, the auditor becomes engrossed with a playful form of the will, which is normally deadly serious. Music was also given a special status in Schopenhauer's aesthetics as it did not rely upon the medium of phenomenal representation. Music artistically presents the will itself, not the way that the will appears to an individual observer. According to Daniel Albright, "Schopenhauer thought that music was the only art that did not merely copy ideas, but actually embodied the will itself."[11] Schopenhauer's moral theory proposed that of three primary moral incentives, compassion, malice and egoism. Compassion is the major motivator to moral expression. Malice and egoism are corrupt alternatives. Schopenhauer was perhaps even more influential in his treatment of man's psychology than he was in the realm of philosophy. Philosophers have not traditionally been impressed by the tribulations of sex, but Schopenhauer addressed it and related concepts forthrightly: ...one ought rather to be surprised that a thing [sex] which plays throughout so important a part in human life has hitherto practically been disregarded by philosophers altogether, and lies before us as raw and untreated material.[12] He gave a name to a force within man which he felt had invariably precedence over reason: the Will to Live (Wille zum Leben), defined as an inherent drive within human beings, and indeed all creatures, to stay alive and to reproduce. Schopenhauer refused to conceive of love as either trifling or accidental, but rather understood it to be an immensely powerful force lying unseen within man's psyche and dramatically shaping the world: The ultimate aim of all love affairs ... is more important than all other aims in man's life; and therefore it is quite worthy of the profound seriousness with which everyone pursues it. What is decided by it is nothing less than the composition of the next generation ...[13] These ideas foreshadowed Darwin's discovery of evolution and Freud's concepts of the libido and the unconscious mind.[14] Schopenhauer's politics were, for the most part, an echo of his system of ethics (the latter being expressed in Die beiden Grundprobleme der Ethik, available in English as two separate books, On the Basis of Morality and On the Freedom of the Will). Ethics also occupies about one quarter of his central work, The World as Will and Representation. In occasional political comments in his Parerga and Paralipomena and Manuscript Remains, Schopenhauer described himself as a proponent of limited government. What was essential, he thought, was that the state should "leave each man free to work out his own salvation", and so long as government was thus limited, he would "prefer to be ruled by a lion than one of [his] fellow rats" — i.e., by a monarch, rather than a democrat. Schopenhauer did, however, share the view of Thomas Hobbes on the necessity of the state, and of state violence, to check the destructive tendencies innate to our species. Schopenhauer, by his own admission, did not give much thought to politics, and several times he writes proudly of how little attention he had paid "to political affairs of [his] day". In a life that spanned several revolutions in French and German government, and a few continent-shaking wars, he did indeed maintain his aloof position of "minding not the times but the eternities". He wrote many disparaging remarks about Germany and the Germans. A typical example is, "For a German it is even good to have somewhat lengthy words in his mouth, for he thinks slowly, and they give him time to reflect."[15] Schopenhauer possessed a distinctly hierarchical conception of the human races, attributing civilizational primacy to the northern "white races" due to their sensitivity and creativity: The highest civilization and culture, apart from the ancient Hindus and Egyptians, are found exclusively among the white races; and even with many dark peoples, the ruling caste or race is fairer in colour than the rest and has, therefore, evidently immigrated, for example, the Brahmans, the Incas, and the rulers of the South Sea Islands. All this is due to the fact that necessity is the mother of invention because those tribes that emigrated early to the north, and there gradually became white, had to develop all their intellectual powers and invent and perfect all the arts in their struggle with need, want and misery, which in their many forms were brought about by the climate. This they had to do in order to make up for the parsimony of nature and out of it all came their high civilization.[16] Despite this, he was adamantly against differing treatment of races, was fervently anti-slavery, and supported the abolitionist movement in the United States. He describes the treatment of "[our] innocent black brothers whom force and injustice have delivered into [the slave-master's] devilish clutches" as "belonging to the blackest pages of mankind's criminal record".[17]

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

the wisdom of life being the first part of arthur schopenhauers aphorismen zur

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

the wisdom of life being the first part of arthur schopenhauers aphorismen zu

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

essays of arthur schopenhauer the wisdom of life arthur schopenhauer 8 1

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

the basis of morality

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Persuasive and humane, this classic offers Schopenhauer's fullest examination of ethical themes. A defiance of Kant's ethics of duty, it proclaims compassion as the basis of morality and outlines a perspective on ethics in which passion and desire correspond to different moral characters, behaviors, and worldviews. --This text refers to an alternate Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

religion a dialogue and other essays

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

CONTENTS Prefatory Note Religion: A Dialogue A Few Words on Pantheism On Books and Reading On Physiognomy Psychological Observations The Christian System --This text refers to an alternate Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

on human nature essays partly posthumous in ethics and politics

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Essays of Arthur Schopenhauer: the Wisdom of Life

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

One of the most unusual works on the literary heritage of Arthur Schopenhauer, a nineteenth century German philosopher known for his atheistic pessimism and philosophical clarity.

Here he tried to oppose epicurean conception to his own, pessimistic and idealistic one. The author aspired to teach people to live a happy, mature, comfortable life, giving voice to the thought that there is a certain concept of wisdom of life, which implies the skill to live easily and calmly. Quoting the ancient and contemporary wise men, the philosopher draws his arguments out of the life experience. We enter here a world of free thought, revealing the secrets of our living, our human nature – upheld by our own unique experience we are able to realize better the course of life and the opportunities to improve it.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Here he tried to oppose epicurean conception to his own, pessimistic and idealistic one. The author aspired to teach people to live a happy, mature, comfortable life, giving voice to the thought that there is a certain concept of wisdom of life, which implies the skill to live easily and calmly. Quoting the ancient and contemporary wise men, the philosopher draws his arguments out of the life experience. We enter here a world of free thought, revealing the secrets of our living, our human nature – upheld by our own unique experience we are able to realize better the course of life and the opportunities to improve it.

Show more

The Essays of Arthur Schopenhauer; The Art of Literature

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

1/5

The book belongs to the pen of the nineteenth century German radical philosopher of pessimism Arthur Schopenhauer, who described himself as the only worthy successor to Kant, assimilated all the negative trends of a disillusioned age. The Art of Literature presents several essays, devoted to the literary form and method, observations upon style, authorship, reputation, criticism and genius: “And whatever may be thought of some of his opinions on matters of detail--on anonymity, for instance, or on the question whether good work is never done for money--there can be no doubt that his general view of literature, and the conditions under which it flourishes, is perfectly sound.”

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Essays of Arthur Schopenhauer; the Art of Controversy

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

In this book you'll find out about sophisms ex homonymia. You'll see links in a chain of reasoning omitted. And false premises, and omitted premises. And non sequiturs. Suppressed majors. Negated minors. Argumentum ad ignorantiam. There is advice about false generalizations. Get your opponent to admit that your examples are true. Do not ask about the validity of the general case, but later act as if this has been admitted as well. Then there are "false choice" arguments, where you pretend that the only alternative to your policy is some manifestly crazy "straw-man" counterplan. And there are false reductio ad absurdums and false counterexamples. There are also suggestive questions, such as asking why something is true, when it may not be true at all. This is a real gem of philosophy literature that is a definite must read.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Schopenhauer Arthur try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Schopenhauer Arthur try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!