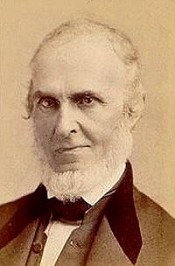

Whittier John Greenleaf

John Greenleaf Whittier (December 17, 1807 – September 7, 1892) was an influential American Quaker poet and ardent advocate of the abolition of slavery in the United States. He is usually listed as one of the Fireside Poets. Whittier was strongly influenced by the Scottish poet, Robert Burns. John Greenleaf Whittier was born to John and Abigail (Hussey) at their rural homestead near Haverhill, Massachusetts, on December 17, 1807.[1] He grew up on the farm in a household with his parents, a brother and two sisters, a maternal aunt and paternal uncle, and a constant flow of visitors and hired hands for the farm. Their farm was not very profitable. There was only enough money to get by. John himself was not cut out for hard farm labor and suffered from bad health and physical frailty his whole life. Although he received little formal education, he was an avid reader who studied his father’s six books on Quakerism until their teachings became the foundation of his ideology. Whittier was heavily influenced by the doctrines of his religion, particularly its stress on humanitarianism, compassion, and social responsibility. Whittier was first introduced to poetry by a teacher. His sister sent his first poem, "The Exile's Departure", to the Newburyport Free Press without his permission and its editor, William Lloyd Garrison, published it on June 8, 1826.[2] As a boy, it was discovered that Whittier was color-blind when he was unable to see a difference between ripe and unripe strawberries.[3] Garrison as well as another local editor encouraged Whittier to attend the recently-opened Haverhill Academy. To raise money to attend the school, Whittier became a shoemaker for a time, and a deal was made to pay part of his tuition with food from the family farm.[4] Before his second term, he earned money to cover tuition by serving as a teacher in a one-room schoolhouse in what is now Merrimac, Massachusetts.[5] He attended Haverhill Academy from 1827 to 1828 and completed a high school education in only two terms. Garrison gave Whittier the job of editor of the National Philanthropist, a Boston-based temperance weekly. Shortly after a change in management, Garrison reassigned him as editor of the weekly American Manufacturer in Boston.[6] Whittier became an out-spoken critic of President Andrew Jackson, and by 1830 was editor of the prominent New England Weekly Review in Hartford, Connecticut, the most influential Whig journal in New England. In 1833 he published The Song of the Vermonters, 1779, which he had anonymously inserted in The New England Magazine. The poem was erroneously attributed to Ethan Allen for nearly sixty years. During the 1830s, Whittier became interested in politics, but after losing a Congressional election in 1832, he suffered a nervous breakdown and returned home at age twenty-five. The year 1833 was a turning point for Whittier; he resurrected his correspondence with Garrison, and the passionate abolitionist began to encourage the young Quaker to join his cause. In 1833, Whittier published the antislavery pamphlet Justice and Expediency,[7] and from there dedicated the next twenty years of his life to the abolitionist cause. The controversial pamphlet destroyed all of his political hopes—as his demand for immediate emancipation alienated both northern businessmen and southern slaveholders—but it also sealed his commitment to a cause that he deemed morally correct and socially necessary. He was a founding member of the American Anti-Slavery Society and signed the Anti-Slavery Declaration of 1833, which he often considered the most significant action of his life. Whittier's political skill made him useful as a lobbyist, and his willingness to badger anti-slavery congressional leaders into joining the abolitionist cause was invaluable. From 1835 to 1838, he traveled widely in the North, attending conventions, securing votes, speaking to the public, and lobbying politicians. As he did so, Whittier received his fair share of violent responses, being several times mobbed, stoned, and run out of town. From 1838 to 1840, he was editor of The Pennsylvania Freeman in Philadelphia,[8] one of the leading antislavery papers in the North, formerly known as the National Enquirer. In May 1838, the publication moved its offices to the newly-opened Pennsylvania Hall on North Sixth Street, which was shortly after burned by a pro-slavery mob.[9] Whittier also continued to write poetry and nearly all of his poems in this period dealt with the problem of slavery. By the end of the 1830s, the unity of the abolitionist movement had begun to fracture. Whittier stuck to his belief that moral action apart from political effort was futile. He knew that success required legislative change, not merely moral suasion. This opinion alone engendered a bitter split from Garrison, and Whittier went on to become a founding member of the Liberty Party in 1839.[8] By 1843, he was announcing the triumph of the fledgling party: "Liberty party is no longer an experiment. It is vigorous reality, exerting... a powerful influence".[10] Whittier also unsuccessfully encouraged Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to join the party.[11] He took editing jobs with the Middlesex Standard in Lowell, Massachusetts and the Essex Transcript in Amesbury until 1844.[8] While in Lowell, he met Lucy Larcom, who became a lifelong friend.[12] In 1845, he began writing his essay "The Black Man" which included an anecdote about John Fountain, a free black who was jailed in Virginia for helping slaves escape. After his release, Fountain went on a speaking tour and thanked Whittier for writing his story.[13] Around this time, the stresses of editorial duties, worsening health, and dangerous mob violence caused him to have a physical breakdown. Whittier went home to Amesbury, and remained there for the rest of his life, ending his active participation in abolition. Even so, he continued to believe that the best way to gain abolitionist support was to broaden the Liberty Party’s political appeal, and Whittier persisted in advocating the addition of other issues to their platform. He eventually participated in the evolution of the Liberty Party into the Free Soil Party, and some say his greatest political feat was convincing Charles Sumner to run on the Free-Soil ticket for the U.S. Senate in 1850. Beginning in 1847, Whittier was editor of Gamaliel Bailey's The National Era,[8] one of the most influential abolitionist newspapers in the North. For the next ten years it featured the best of his writing, both as prose and poetry. Being confined to his home and away from the action offered Whittier a chance to write better abolitionist poetry; he was even poet laureate for his party. Whittier's poems often used slavery to symbolize all kinds of oppression (physical, spiritual, economic), and his poems stirred up popular response because they appealed to feelings rather than logic. Whittier produced two collections of antislavery poetry: Poems Written during the Progress of the Abolition Question in the United States, between 1830 and 1838 and Voices of Freedom (1846). He was an elector in the presidential election of 1860 and of 1864, voting for Abraham Lincoln both times.[14] The passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 ended both slavery and his public cause, so Whittier turned to other forms of poetry for the remainder of his life. One of his most enduring works, Snow-Bound, was first published in 1866. Whittier was surprised by its financial success, earning some $10,000 from the first edition.[15] In 1867, Whittier asked James Thomas Fields to get him a ticket to a reading by Charles Dickens during the British author's visit to the United States. After the event, he wrote a letter describing his experience: Whittier spent the last few winters of his life, from 1876 to 1892, at Oak Knoll, the home of his cousins in Danvers, Massachusetts.[17] Whittier died on September 7, 1892, at a friend's home in Hampton Falls, New Hampshire.[18] He is buried in Amesbury, Massachusetts.[19] Whittier's first two published books were Legends of New England (1831) and the poem Moll Pitcher (1832). In 1833 he published The Song of the Vermonters, 1779, which he had anonymously inserted in The New England Magazine. The poem was erroneously attributed to Ethan Allen for nearly sixty years. This use of poetry in the service of his political beliefs is illustrated by his book Poems Written during the Progress of the Abolition Question. Highly regarded in his lifetime and for a period thereafter, he is now largely remembered for his patriotic poem Barbara Frietchie, Snow-Bound, and a number of poems turned into hymns. Of these the best known is Dear Lord and Father of Mankind, taken from his poem The Brewing of Soma. On its own, the hymn appears sentimental, though in the context of the entire poem, the stanzas make greater sense, being intended as a contrast with the fevered spirit of pre-Christian worship. Whittier's Quaker universalism is better illustrated, however, by the hymn that begins: His sometimes contrasting sense of the need for strong action against injustice can be seen in his poem "To Rönge" in honor of Johannes Ronge, the German religious figure and rebel leader of the 1848 rebellion in Germany: Whittier's poem "At Port Royal 1861" describes the experience of Northern abolitionists arriving at Port Royal, South Carolina, as teachers and missionaries for the slaves who had been left behind when their owners fled because the Union Navy would arrive to blockade the coast. The poem includes the "Song of the Negro Boatmen," written in dialect: Of all the poetry inspired by the Civil War, the "Song of the Negro Boatmen" was one of the most widely printed,[20] and though Whittier never actually visited Port Royal, an abolitionist working there described his "Song of the Negro Boatmen" as "wonderfully applicable as we were being rowed across Hilton Head Harbor among United States gunboats."[21] Nathaniel Hawthorne dismissed Whittier's Literary Recreations and Miscellanies (1854): "Whittier's book is poor stuff! I like the man, but have no high opinion either of his poetry or his prose".[22] Editor George Ripley, however, found Whittier's poetry refreshing and said it had a "stately movement of versification, grandeur of imagery, a vein of tender and solemn pathos, cheerful trust" and a "pure and ennobling character".[23] Boston critic Edwin Percy Whipple noted Whittier's moral and ethical tone mingled with sincere emotion. He wrote, "In reading this last volume, I feel as if my soul had taken a bath in holy water."[24] Later scholars and critics questioned the depth of Whittier's poetry. One was Karl Keller, who noted, "Whittier has been a writer to love, not to belabor.[25]

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

The Conflict with Slavery and Others,Complete,Volume VII,The Works of Whittier: the Conflict with Slavery,Politicsand Reform,the Inner Life and Criticism

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Criticism,Part 4,from Volume VII,The Works of Whittier: the Conflict with Slavery,Politicsand Reform,the Inner Life and Criticism

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

The Conflict with Slavery and Others,Complete,Volume VII,The Works of Whittier: the Conflict with Slavery,Politicsand Reform,the Inner Life and Criticism

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Criticism,Part 4,from Volume VII,The Works of Whittier: the Conflict with Slavery,Politicsand Reform,the Inner Life and Criticism

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Inner Life,Part 3,from Volume VII,The Works of Whittier: the Conflict with Slavery,Politicsand Reform,the Inner Life and Criticism

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Reform and Politics,Part 2,from Volume VII,The Works of Whittier: the Conflict with Slavery,Politicsand Reform,the Inner Life and Criticism

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Conflict with Slavery,Part 1,from Volume VII,The Works of Whittier: the Conflict with Slavery,Politicsand Reform,the Inner Life and Criticism

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Old Portraits,Modern Sketches,Personal Sketches and TributesComplete,Volume VI.,the Works of Whittier

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Historical Papers,Part 3,from Volume VI.,The Works of Whittier: Old Portraits and Modern Sketches

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Personal Sketches and Tributes,Part 2,from Volume VI.,The Works of Whittier: Old Portraits and Modern Sketches

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Old Portraits,Part 1,from Volume VI.,The Works of Whittier: Old Portraits and Modern Sketches

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Tales and Sketches,CompleteVolume V.,the Works of Whittier: Tales and Sketches

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Tales and SketchesPart 3,from Volume V.,the Works of Whittier: Tales and Sketches

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

My Summer with Dr. SingletaryPart 2,from Volume V.,the Works of Whittier: Tales and Sketches

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Margaret Smith's JournalPart 1,from Volume V.,the Works of Whittier: Tales and Sketches

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Personal Poems,CompleteVolume IV.,the Works of Whittier: Personal Poems

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

At SundownPart 5,from Volume IV.,the Works of Whittier: Personal Poems

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Tent on the Beach and OthersPart 4,from Volume IV.,the Works of Whittier: Personal Poems

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Occasional PoemsPart 3 from Volume IV.,the Works of Whittier: Personal Poems

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Whittier John Greenleaf try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Whittier John Greenleaf try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!