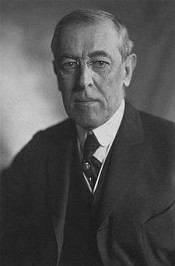

Wilson Woodrow

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856–February 3, 1924)[1] was the 28th President of the United States. A leading intellectual of the Progressive Era, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913. With Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft dividing the Republican Party vote, Wilson was elected President as a Democrat in 1912. To date he is the only President to hold a doctorate of philosophy (PhD) degree and the only President to serve in a political office in New Jersey before election to the Presidency. In his first term, Wilson persuaded a Democratic Congress to pass the Federal Reserve Act,[2] Federal Trade Commission, the Clayton Antitrust Act, the Federal Farm Loan Act and America's first-ever federal progressive income tax in the Revenue Act of 1913. In a move that garnered a backlash from civil rights groups, and is still criticized today, Wilson allowed segregation in many federal agencies,[3][4] which involved firing black workers from numerous posts.[5] Narrowly re-elected in 1916, Wilson's second term centered on World War I. He based his re-election campaign around the slogan "he kept us out of the war," but U.S. neutrality would be short-lived. When the German government proposed to Mexico in the Zimmermann Telegram a military alliance in a war against the U.S. (promising the return of Arizona, New Mexico and Texas), and began unrestricted submarine warfare, Wilson in April 1917 asked Congress to declare war. He focused on diplomacy and financial considerations, leaving the waging of the war primarily in the hands of the Army. On the home front, he began the United States' first draft since the US civil war in 1917, raised billions in war funding through Liberty Bonds, set up the War Industries Board, promoted labor union growth, supervised agriculture and food production through the Lever Act, took over control of the railroads, enacted the first federal drug prohibition, and suppressed anti-war movements. National women's suffrage was also achieved under Wilson's presidency. In the late stages of the war, Wilson took personal control of negotiations with Germany, including the armistice. He issued his Fourteen Points, his view of a post-war world that could avoid another terrible conflict. He went to Paris in 1919 to create the League of Nations and shape the Treaty of Versailles, with special attention on creating new nations out of defunct empires. Largely for his efforts to form the League, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1919, during the bitter fight with the Republican-controlled Senate over the U.S. joining the League of Nations, Wilson collapsed with a debilitating stroke. He refused to compromise, effectively destroying any chance for ratification. The League of Nations was established anyway, but the United States never joined. Wilson's idealistic internationalism, now referred to as "Wilsonianism", which calls for the United States to enter the world arena to fight for democracy, has been a contentious position in American foreign policy, serving as a model for "idealists" to emulate and "realists" to reject ever since. Wilson was born in Staunton, Virginia on December 28, 1856 as the third of four children of Reverend Dr. Joseph Ruggles Wilson (1822–1903) and Jessie Janet Woodrow (1826–1888).[1] His ancestry was Scots-Irish and Scottish. His paternal grandparents immigrated to the United States from Strabane, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland, in 1807. His mother was born in Carlisle to Scottish parents. His grandparents' whitewashed house has become a tourist attraction in Northern Ireland. Descendants of the Wilsons still live in the farmhouse next door to it.[6] Wilson's father was originally from Steubenville, Ohio, where his grandfather published a newspaper, The Western Herald and Gazette, that was pro-tariff and abolitionist.[7] Wilson's parents moved South in 1851 and identified with the Confederacy. His father defended slavery, owned slaves and set up a Sunday school for them. They cared for wounded soldiers at their church. The father also briefly served as a chaplain to the Confederate Army.[8] Woodrow Wilson's earliest memory, from the age of three, was of hearing that Abraham Lincoln had been elected and that a war was coming. Wilson would forever recall standing for a moment at Robert E. Lee's side and looking up into his face.[8] Wilson’s father was one of the founders of the Southern Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS) after it split from the northern Presbyterians in 1861. Joseph R. Wilson served as the first permanent clerk of the southern church’s General Assembly, was Stated Clerk from 1865–1898 and was Moderator of the PCUS General Assembly in 1879. Wilson spent the majority of his childhood, up to age 14, in Augusta, Georgia, where his father was minister of the First Presbyterian Church.[9] Wilson was over ten years of age before he learned to read. His difficulty reading may have indicated dyslexia,[10] but as a teenager he taught himself shorthand to compensate.[11] He was able to achieve academically through determination and self-discipline. He studied at home under his father's guidance and took classes in a small school in Augusta.[12] During Reconstruction, Wilson lived in Columbia, South Carolina, the state capital, from 1870–1874, where his father was professor at the Columbia Theological Seminary.[13] In 1873, he spent a year at Davidson College in North Carolina, then transferred to Princeton as a freshman, graduating in 1879, becoming a member of Phi Kappa Psi fraternity. Beginning in his second year, he read widely in political philosophy and history. Wilson credited the British parliamentary sketch-writer Henry Lucy as his inspiration to enter public life. He was active in the undergraduate American Whig-Cliosophic Society discussion club, and organized a separate Liberal Debating Society.[14] In 1879, Wilson attended law school at University of Virginia for one year. Although he never graduated, during his time at the University he was heavily involved in the Virginia Glee Club and the Jefferson Literary and Debating Society, serving as the Society's president.[15] His frail health dictated withdrawal, and he went home to Wilmington, North Carolina where he continued his studies.[16] He entered graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University in 1883 and three years later received a PhD in history and political science. After completing his doctoral dissertation, Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics, in 1886, he received academic appointments at Bryn Mawr College (1885–88) and Wesleyan University (1888–90).[17] Wilson’s mother was possibly a hypochondriac and Wilson himself seemed to think that he was often in poorer health than he really was. However, he did suffer from hypertension at a relatively early age and may have suffered his first stroke at age 39.[18] In 1885, he married Ellen Louise Axson, the daughter of a minister from Rome, Georgia. They had three daughters: Margaret Woodrow Wilson (1886–1944); Jessie Wilson (1887–1933); and Eleanor R. Wilson (1889–1967)[1] Axson died in 1914, and Wilson married Edith Galt, a direct descendant of the famous Native American Pocahontas,[19] in 1915. Wilson is one of only three presidents to be widowed while still in office.[20] Wilson was an early automobile enthusiast, and he took daily rides while he was President. His favorite car was a 1919 Pierce-Arrow, in which he preferred to ride with the top down.[21] His enjoyment of motoring made him an advocate of funding for public highways.[22] Wilson was an avid baseball fan. In 1916, he became the first sitting president to attend a World Series game. Wilson had been a center fielder during his Davidson College days. When he transferred to Princeton he was unable to make the varsity team and so became the team's assistant manager. He was the first President officially to throw out a first ball at a World Series.[23] He cycled regularly, including several cycling vacations in the English Lake District.[24] Unable to cycle around Washington, D.C. as President, Wilson took to playing golf, although he played with more enthusiasm than skill.[25] Wilson holds the record of all the presidents for the most rounds of golf,[25] over 1,000, or almost one every other day. During the winter, the Secret Service would paint golf balls with black paint so Wilson could hit them around in the snow on the White House lawn.[26] In January 1882, he started his first law practice in Atlanta. One of Wilson’s University of Virginia classmates, Edward Ireland Renick, invited him to join his new law practice as partner. Wilson joined him there in May 1882. He passed the Georgia Bar. On October 19, 1882, he appeared in court before Judge George Hillyer to take his examination for the bar, which he passed easily. Competition was fierce in the city with 143 other lawyers, so with few cases to keep him occupied, Wilson quickly grew disillusioned.[27] Moreover, Wilson had studied law to eventually enter politics, but he discovered that he could not continue his study of government and simultaneously continue the reading of law necessary to stay proficient. In April 1883, Wilson applied to the new Johns Hopkins University to study for a Ph.D. in history and political science, which he completed in 1886.[27] Wilson served as president of the American Political Science Association in 1910, and remains the only U.S. president to have earned a Ph.D. Wilson came of age in the decades after the American Civil War, when Congress was leading – "the gist of all policy is decided by the legislature" —and corruption was rampant. Instead of focusing on individuals in explaining where American politics went wrong, Wilson focused on the American constitutional structure.[28] Under the influence of Walter Bagehot's The English Constitution, Wilson saw the United States Constitution as pre-modern, cumbersome, and open to corruption. An admirer of Parliament (though he did not visit Great Britain until 1919), Wilson favored a parliamentary system for the United States. Writing in the early 1880s:

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

Congressional GovernmentA Study in American Politics

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

In Our First Year of the WarMessages and Addresses to the Congress and the People,March 5,1917 to January 6,1918

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The New FreedomA Call For the Emancipation of the Generous Energies of a People

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

Congressional GovernmentA Study in American Politics

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

In Our First Year of the WarMessages and Addresses to the Congress and the People,March 5,1917 to January 6,1918

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The New FreedomA Call For the Emancipation of the Generous Energies of a People

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Why We Are at War : Messages to the Congress January to April 1917

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Why We Are at War : Messages to the Congress January to April 1917. please visit www.valdebooks.com for a full list of titles

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

When a Man Comes to Himself

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

This volume is produced from digital images created through the University of Michigan University Library's preservation reformatting program. The Library seeks to preserve the intellectual content of items in a manner that facilitates and promotes a variety of uses. The digital reformatting process results in an electronic version of the text that can both be accessed online and used to create new print copies. This book and thousands of others can be found in the digital collections of the University of Michigan Library. The University Library also understands and values the utility of print, and makes reprints available through its Scholarly Publishing Office.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

State of the Union Address

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

This book was converted from its physical edition to the digital format by a community of volunteers. You may find it for free on the web. Purchase of the Kindle edition includes wireless delivery. --This text refers to the Kindle Edition edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

On Being Human

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

United States President Woodrow Wilson's classic essay, reprinted in facsimile from the 1916 edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The New Freedom

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

1/5

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) was the twentyeighth President of the United States. A devout Presbyterian and leading intellectual of the Progressive Era, he served as president of Princeton University then became the reform governor of New Jersey in 1910. With Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft dividing the Republican vote, Wilson was elected President as a Democrat in 1912. He proved highly successful in leading a Democratic Congress to pass major legislation including the Federal Trade Commission, the Clayton Antitrust Act, the Underwood Tariff, the Federal Farm Loan Act and most notably the Federal Reserve System. Wilson's idealistic internationalism, whereby the U. S. enters the world arena to fight for democracy, progressiveness, and liberalism, has been a highly controversial position in American foreign policy, serving as a model for "idealists" to emulate or "realists" to reject for the following century. His works include: When a Man Comes to Himself (1910), The New Freedom (1913), On Being Human (1916), President Wilson's Addresses (1917), State of the Union (1918) and Why We Are at War (1918). --This text refers to an alternate Paperback edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

In Our First Year of the War

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

FOREWORD This book opens with the second inaugural address and contains the President's messages and addresses since the United States was forced to take up arms against Germany. These pages may be said to picture not only official phases of the great crisis, but also the highest significance of liberty and democracy and the reactions of President and people to the great developments of the times. The second Inaugural Address with its sense of solemn responsibility serves as a prophecy as well as prelude to the declaration of war and the message to the people which followed so soon. The extracts from the Conscription Proclamation, the messages on Conservation and the Fixing of Prices, the Appeal to Business Interests, the Address to the Federation of Labor and the Railroad messages present the solid every-day realities and the vast responsibilities of war-time as they affect every American. These are concrete messages which should be at hand for frequent reference, just as the uplift and inspiration of lofty appeals like the Memorial Day and Flag Day addresses should be a constant source of inspiration. There are also the clarifying and vigorous definitions of American purpose afforded in utterances like the statement to Russia, the reply to the communication of the Pope, and, most emphatically, the President's restatement of War Aims on January 8th. These and other state papers from the early spring of 1917 to January, 1918, have a significance and value in this collected form which has been attested by the many requests that have come to Harper & Brothers, as President Wilson's publishers, for a war volume of the President's messages to follow Why We Are At War. As a matter of course, the President has been consulted in regard to the plan of publication, and the conditions which he requested have been observed. For title, arrangement, headings, and like details the publishers are responsible. They have held the publication of the President's words of enlightenment and inspiration to be a public service. And they think that there is no impropriety in adding that in the case of this book, and Why We Are At War, the American Red Cross receives all author's royalties. In the case of the former book the evolution of events which led to war was illustrated in messages from January to April 15th. In the preparation of this book, which begins with the second inaugural, it has seemed desirable to present practically all the messages of war-time, and therefore three papers are included which appeared in the former and smaller book, in addition to the twenty-one messages and addresses which have been collected for this volume. --This text refers to the Kindle Edition edition.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

- Literature & Fiction / Genre Fiction / War

- Law / Perspectives on Law / Jurisprudence

- Nonfiction / Politics

- Literature & Fiction / Classics

- Books / American literature / 20th century / History and criticism

- Literature & Fiction / Books & Reading

- Travel / United States

- Books / Gay men / United States

- Books / Bonds / Canada / Statistics

if you like Wilson Woodrow try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

- Literature & Fiction / Genre Fiction / War

- Law / Perspectives on Law / Jurisprudence

- Nonfiction / Politics

- Literature & Fiction / Classics

- Books / American literature / 20th century / History and criticism

- Literature & Fiction / Books & Reading

- Travel / United States

- Books / Gay men / United States

- Books / Bonds / Canada / Statistics

if you like Wilson Woodrow try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!