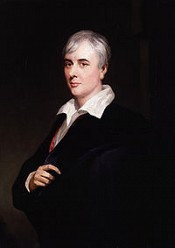

Wise Thomas James

George Henry Borrow (5 July 1803 – 26 July 1881) was an English author who wrote novels and travelogues based on his own experiences around Europe. Over the course of his wanderings, he developed a close affinity with the Romani people of Europe. They figure prominently in his work. His best known book is The Bible in Spain; Lavengro is autobiographical, and Romany Rye is about his time with the English Romanichal (gypsies). Borrow was born at East Dereham, Norfolk, the son of Army recruiting officer Thomas Borrow (1758-1824)[1] and farmer's daughter Ann Perfrement (1772-1858)[2]. He was educated at the Royal High School of Edinburgh and Norwich Grammar School. He studied law, but languages and literature became his main interests. In 1825, Borrow began his first major European journey, walking in France and Germany. Over the next few years he visited Russia, Portugal, Spain and Morocco, acquainting himself with the people and languages of the various countries he visited. After his marriage on 23 April 1840[1], he settled near Lowestoft but continued to travel both inside and outside the UK. Having a military father, Borrow had a childhood of growing up at different posts. In the autumn of 1815, he accompanied the regiment to Clonmel in Ireland. There he attended the Protestant Academy, where he learned to read Latin and Greek ‘from a nice old clergyman’. He was also introduced to the Irish language by a fellow student named Murtagh, who tutored him in return for a pack of playing cards. In keeping with the political friction of the time, he learned to sing "the glorious tune 'Croppies Lie Down' " at the military barracks. He was introduced to horsemanship and learned to ride without a saddle. After less than a year in Ireland, the regiment returned to Norwich. With the threat of war having receded, the strength of the unit was greatly reduced.[3] Because of Borrow's precocious linguistic skills, as a youth he became the protegé of the Norwich-born scholar William Taylor. Borrow depicts Taylor, an advocate of German Romantic literature, in his semi-autobiographical novel Lavengro (1851). In his recollection of his early youth in Norwich some thirty years earlier, Borrow depicts an old man (Taylor) and a young man (Borrow) discussing the merits of German literature, including Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther. Taylor confesses himself to be no admirer of either The Sorrows of Young Werther or its author but nevertheless states- With Taylor’s encouragement, Borrow embarked upon his first translation: Von Klinger's version of the Faust legend, entitled Faustus, his Life, Death and Descent into Hell, first published in St.Petersburg in 1791. In his translation, Borrow altered the name of one city, thus making one passage of the legend read -- For his lampooning of Norwich society, the young Borrow earned the humiliation of having public subscription libraries burn his first publication. George Borrow was a linguist adept at acquiring new languages. He informed the British and Foreign Bible Society that- He left Norwich to travel to Saint Petersburg on the 13th of August 1833. As an agent of the Bible Society, Borrow was charged with supervising a translation of the Bible into Manchu. As a traveller, he was overwhelmed by the beauty of Saint Petersburg, writing -- During his two-year sojourn in Russia, Borrow called upon writer Alexander Pushkin. The poet was out on a social visit. He left two copies of his translations of Pushkin’s literary works and later Pushkin expressed his regret at not meeting him. Borrow described the Russian people as -- Borrow had a life-long empathy with nomadic people such as Gypsies. He was fascinated by gypsy customs, songs and dance. He became so familiar with their language as to publish a dictionary of it. In the summer of 1835, he visited Russian gypsies camped outside Moscow. His impressions formed part of the opening chapter of his Zincali: or an account of the Gypsies of Spain (1841). With his mission of supervising a Manchu translation of the Bible completed, Borrow returned to Norwich in September 1835. In his report to the Bible Society he confessed -- Such was Borrow's success that on 11 November 1835 he set off for Spain, once more as an agent of the Bible society. Borrow claimed to have stayed in Spain for nearly five years. His reminiscences of Spain were the basis of his travelogue The Bible in Spain (1843). He wrote sharply: The above quotation shows Borrow's empathy with native, indigenous peoples, and also his occasional bout of prejudice; here in observing the latent stirrings of 19th century American Imperialism. In 1840 Borrow's career with the Bible Society came to an end, and he married Mary Clarke, a widow with a grown-up daughter called Henrietta, and a small estate on Oulton Broad in Suffolk. There Borrow began to write his books. The Zincali (1841) was moderately successful, and The Bible in Spain (1843) was a huge success, making Borrow a celebrity overnight. But the eagerly awaited Lavengro (1851) and The Romany Rye (1857) puzzled many readers, who were not sure how much was fact and how much fiction (a question debated to this day). Borrow made one more overseas journey, across Europe to Istanbul in 1844, but the rest of his travels were in the UK, long walking tours in Scotland, Wales, Ireland, Cornwall and the Isle of Man. Of these, only the Welsh tour yielded a book, Wild Wales (1862). Borrow's restlessness, perhaps, led to the family living in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, in the 1850s, and in London in the 1860s. Borrow visited the Romanichal Gypsy encampments in Wandsworth and Battersea, and wrote one more book, Romano Lavo-Lil, a wordbook of the Anglo-Romany dialect (1874). Mary Borrow died in 1869, and in 1874 Borrow returned to their home in Oulton, where he was later joined by his stepdaughter Henrietta and her husband, who looked after him until his death on 26 July 1881 in Oulton, Suffolk. He is buried with his wife in Brompton Cemetery, London.

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

coleridgeiana being a supplement to the bibliography of coleridge

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Originally published in 1919. This volume from the Cornell University Library's print collections was scanned on an APT BookScan and converted to JPG 2000 format by Kirtas Technologies. All titles scanned cover to cover and pages may include marks notations and other marginalia present in the original volume.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a bibliography of the writings of joseph conrad 1895 1920

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a bibliography of the writings in prose and verse of william wordsworth

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

coleridgeiana being a supplement to the bibliography of coleridge

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Originally published in 1919. This volume from the Cornell University Library's print collections was scanned on an APT BookScan and converted to JPG 2000 format by Kirtas Technologies. All titles scanned cover to cover and pages may include marks notations and other marginalia present in the original volume.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a bibliography of the writings of joseph conrad 1895 1920

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a bibliography of the writings in prose and verse of william wordsworth

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a bibliography of the writings in prose and verse of walter savage landor

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Originally published in 1919. This volume from the Cornell University Library's print collections was scanned on an APT BookScan and converted to JPG 2000 format by Kirtas Technologies. All titles scanned cover to cover and pages may include marks notations and other marginalia present in the original volume.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a bibliography of the writings in prose and verse of the members of the bront

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

a bibliography of the writings in prose and verse of elizabeth barrett browning

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

A Bibliography of the writings in Prose and Verse of George Henry Borrow

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Originally published in 1914. This volume from the Cornell University Library's print collections was scanned on an APT BookScan and converted to JPG 2000 format by Kirtas Technologies. All titles scanned cover to cover and pages may include marks notations and other marginalia present in the original volume.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

- Books

- Books / Children's Books / History & Historical Fiction

- Science / Nature & Ecology / Water Supply & Land Use

- Biographies & Memoirs

- Nonfiction / Politics / General

- Books / Agricultural exhibitions / Nova Scotia / Kentville

- Literature & Fiction

- Literature & Fiction / Classics

- Books / Photography

- Travel / Europe / Belgium

if you like Wise Thomas James try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

- Books

- Books / Children's Books / History & Historical Fiction

- Science / Nature & Ecology / Water Supply & Land Use

- Biographies & Memoirs

- Nonfiction / Politics / General

- Books / Agricultural exhibitions / Nova Scotia / Kentville

- Literature & Fiction

- Literature & Fiction / Classics

- Books / Photography

- Travel / Europe / Belgium

if you like Wise Thomas James try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!