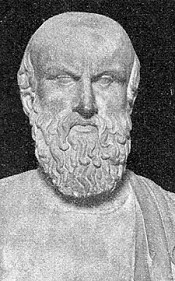

aeschylus

Aeschylus (pronounced /ˈɛskɨləs/ or /ˈiːskɨləs/, Greek: Αἰσχύλος, Aiskhulos, c. 525 BC/524 BC – c. 456 BC/455 BC) was an ancient Greek playwright. He is often recognized as the father of tragedy,[1][2] and is the earliest of the three Greek tragedians whose plays survive, the others being Sophocles and Euripides. According to Aristotle, he expanded the number of characters in plays to allow for conflict among them; previously, characters interacted only with the chorus. Only seven of an estimated seventy to ninety plays by Aeschylus have survived into modern times; one of these plays, Prometheus Bound, is widely thought to be the work of a later author. At least one of Aeschylus' works was influenced by the Persian invasion of Greece, which took place during his lifetime. His play The Persians remains a good primary source of information about this period in Greek history. The war was so important to the Greeks and to Aeschylus himself that, upon his death around 456 BC, his epitaph commemorated his participation in the Greek victory at Marathon rather than to his success as a playwright. There are no reliable sources for the life of Aeschylus. He was said to have been born in c. 525 BC in Eleusis, a small town about 27 kilometers northwest of Athens, which is nestled in the fertile valleys of western Attica,[3] though the date is most likely based on counting back forty years from his first victory in the Great Dionysia. His family was both wealthy and well-established; his father Euphorion was a member of the Eupatridae, the ancient nobility of Attica.[4] As a youth, he worked at a vineyard until, according to the 2nd-century AD geographer Pausanias, the god Dionysus visited him in his sleep and commanded him to turn his attention to the nascent art of tragedy.[4] As soon as he woke from the dream, the young Aeschylus began writing a tragedy, and his first performance took place in 499 BC, when he was only 26 years old;[3][4] He would eventually win his first victory at the City Dionysia in 484 BC.[4][5] The Persian Wars would play a large role in the playwright's life and career. In 490 BC, Aeschylus and his brother Cynegeirus fought to defend Athens against Darius's invading Persian army at the Battle of Marathon.[3] The Athenians, though outnumbered, encircled and slaughtered the Persian army. This pivotal defeat ended the first Persian invasion of Greece proper and was celebrated across the city-states of Greece.[3] Though Athens was victorious, Cynegeirus died in the battle.[3] In 480, Aeschylus was called into military service again, this time against Xerxes' invading forces at the Battle of Salamis, and perhaps, too, at the Battle of Plataea in 479.[3] Salamis holds a prominent place in The Persians, his oldest surviving play, which was performed in 472 BC and won first prize at the Dionysia.[6] Aeschylus was one of many Greeks who had been initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries, a cult to Demeter based in his hometown of Eleusis.[7] As the name implies, members of the cult were supposed to have gained some sort of mystical, secret knowledge. Firm details of the Mysteries' specific rites are sparse, as members were sworn under the penalty of death not to reveal anything about the Mysteries to non-initiates. Nevertheless, according to Aristotle some thought that Aeschylus had revealed some of the cult's secrets on stage.[8] According to other sources, an angry mob tried to kill Aeschylus on the spot, but he fled the scene. When he stood trial for his offense, Aeschylus pleaded ignorance and was only spared because of his brave service in the Persian Wars. Aeschylus traveled to Sicily once or twice in the 470s BC, having been invited by Hieron, tyrant of Syracuse, a major Greek city on the eastern side of the island; during one of these trips he produced The Women of Aetna (in honor of the city founded by Hieron) and restaged his Persians.[3] By 473 BC, after the death of Phrynichus, one of his chief rivals, Aeschylus was the yearly favorite in the Dionysia, winning first prize in nearly every competition.[3] In 458 BC, he returned to Sicily for the last time, visiting the city of Gela where he died in 456 or 455 BC. It is claimed that he was killed by a tortoise which fell out of the sky after it was dropped by an eagle, but this story is very likely apocryphal.[9] Aeschylus' work was so respected by the Athenians that after his death, his were the only tragedies allowed to be restaged in subsequent competitions.[3] His sons Euphorion and Euæon and his nephew Philocles would follow in his footsteps and become playwrights themselves.[3] The inscription on Aeschylus' gravestone makes no mention of his theatrical renown, commemorating only his military achievements: The Greek art of the drama had its roots in religious festivals for the gods, chiefly Dionysus, the god of wine.[5] During Aeschylus' lifetime, dramatic competitions became part of the City Dionysia in the spring.[5] The festival began with an opening procession, continued with a competition of boys singing dithyrambs, and culminated in a pair of dramatic competitions.[11] The first competition, which Aeschylus would have participated in, was for the tragedians, and consisted of three playwrights each presenting three tragic plays followed by a shorter comedic satyr play.[11] A second competition of five comedic playwrights followed, and the winners of both competitions were chosen by a panel of judges.[11] Aeschylus entered many of these competitions in his lifetime, and various ancient sources attribute between seventy and ninety plays to him.[1][12] Only seven tragedies have survived intact: The Persians, Seven against Thebes, The Suppliants, the trilogy known as The Oresteia, consisting of the three tragedies Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers and The Eumenides, and Prometheus Bound (whose authorship is disputed). With the exception of this last play—the success of which is uncertain—all of Aeschylus' extant tragedies are known to have won first prize at the City Dionysia. The Alexandrian Life of Aeschylus indicates that the playwright took the first prize at the City Dionysia thirteen times. This compares favorably with Sophocles' reported eighteen victories (with a substantially larger catalogue, at an estimated 120 plays), and dwarfs the five victories of Euripides (who featured a catalogue of roughly 90 plays). One hallmark of Aeschylean dramaturgy appears to have been his tendency to write connected trilogies in which each play serves as a chapter in a continuous dramatic narrative.[13] The Oresteia is the only wholly extant example of this type of connected trilogy, but there is ample evidence that Aeschylus wrote such trilogies often. The comic satyr plays that would follow his dramatic trilogies often treated a related mythic topic. For example, the Oresteia's satyr play Proteus treated the story of Menelaus's detour in Egypt on his way home from the Trojan War. Based on the evidence provided by a catalogue of Aeschylean play titles, scholia, and play fragments recorded by later authors, it is assumed that three other of Aeschylus' extant plays were components of connected trilogies: Seven against Thebes being the final play in an Oedipus trilogy, and The Suppliants and Prometheus Bound each being the first play in a Danaid trilogy and Prometheus trilogy, respectively (see below). Scholars have moreover suggested several completely lost trilogies derived from known play titles. A number of these trilogies treated myths surrounding the Trojan War. One—collectively called the Achilleis and comprising the titles Myrmidons, Nereids and Phrygians (alternately, The Ransoming of Hector)—recounts Hector's death at the hands of Achilles and the subsequent holding of Hector's body for ransom; another trilogy apparently recounts the entry of the Trojan ally Memnon into the war, and his death at the hands of Achilles (Memnon and The Weighing of Souls being two components of the trilogy); The Award of the Arms, The Phrygian Women, and The Salaminian Women suggest a trilogy about the madness and subsequent suicide of the Greek hero Ajax; Aeschylus also seems to have treated Odysseus' return to Ithaca after the war (including his killing of his wife Penelope's suitors and its consequences) with a trilogy consisting of The Soul-raisers, Penelope and The Bone-gatherers. Other suggested trilogies touched on the myth of Jason and the Argonauts (Argô, Lemnian Women, Hypsipylê); the life of Perseus (The Net-draggers, Polydektês, Phorkides); the birth and exploits of Dionysus (Semele, Bacchae, Pentheus); and the aftermath of the war portrayed in Seven against Thebes (Eleusinians, Argives (or Argive Women), Sons of the Seven).[14] The earliest of the plays that still exists is The Persians (Persai), performed in 472 BC and based on experiences in Aeschylus' own life, specifically the Battle of Salamis.[15] It is unique among Greek tragedies in treating a recent historical event rather than a heroic or divine myth.[1] The Persians focuses on the popular Greek theme of hubris by blaming Persia's loss on the overwhelming pride of its king.[15] It opens with the arrival of a messenger in Susa, the Persian capital, bearing news of the catastrophic Persian defeat at Salamis to Atossa, the mother of the Persian King Xerxes. Atossa then travels to the tomb of Darius, her husband, where his ghost appears to explain the cause of the defeat. It is, he says, the result of Xerxes' hubris in building a bridge across the Hellespont, an action which angered the gods. Xerxes appears at the end of the play, not realizing the cause of his defeat, and the play closes to lamentations by Xerxes and the chorus.[16] Seven against Thebes (Hepta epi Thebas), which was performed in 467 BC, picks up a contrasting theme, that of fate and the interference of the gods in human affairs.[15] It also marks the first known appearance in Aeschylus' work of a theme which would continue through his plays, that of the polis (the city) being a vital development of human civilization.[17] The play tells the story of Eteocles and Polynices, the sons of the shamed King of Thebes, Oedipus. The sons agree to alternate in the throne of the city, but after the first year Eteocles refuses to step down, and Polynices wages war to claim his crown. The brothers go on to kill each other in single combat, and the original ending of the play consisted of lamentations for the dead brothers. A new ending was added to the play some fifty years later: Antigone and Ismene mourn their dead brothers, a messenger enters announcing an edict prohibiting the burial of Polynices; and finally, Antigone declares her intention to defy this edict.[18] The play was the third in a connected Oedipus trilogy; the first two plays were Laius and Oedipus, likely treating those elements of the Oedipus myth detailed most famously in Sophocles' Oedipus the King. The concluding satyr play was The Sphinx.[19]

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like aeschylus try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like aeschylus try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to read a book that interests you? It’s EASY!

Create an account and send a request for reading to other users on the Webpage of the book!