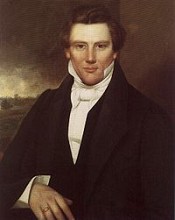

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Joseph Smith, Jr. (December 23, 1805 – June 27, 1844) was the founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, also known as Mormonism, and an important religious and political figure during the 1830s and 1840s. In 1827, Smith began to gather a religious following after announcing that an angel had shown him a set of golden plates describing a visit of Jesus to the indigenous peoples of the Americas. In 1830, Smith published what he said was a translation of these plates as the Book of Mormon, and the same year he organized the Church of Christ. For most of the 1830s, Smith lived in Kirtland, Ohio, which remained the headquarters of the church until the cost of building a large temple, financial collapse, and conflict with disaffected members encouraged him to gather the church to the Latter Day Saint settlement in Missouri. There, tensions between Mormons and non-Mormons escalated into the 1838 Mormon War. Smith and his people then settled in Nauvoo, Illinois where they began building a second temple. After being accused of practicing polygamy, and of aspiring to create a theocracy, Smith, as mayor of Nauvoo and with the support of the city council, directed the suppression of a local newspaper that had published accusations against him, leading to his assassination by a mob. Smith's followers consider him a prophet and have canonized some of his revelations as sacred texts on par with the Bible. His legacy includes several religious denominations, the largest of which, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, has millions of adherents.[1] Joseph Smith, Jr. was born on December 23, 1805, in Sharon, Vermont to Joseph and Lucy Mack Smith. In 1816, the family moved to the village of Palmyra in western New York, and soon obtained a mortgage for a 100-acre farm in the nearby town of Manchester in 1818. This area experienced intense religious activity during the Second Great Awakening. Although he may never have joined any church during his youth,[2] he participated in church classes,[3] read the Bible, and was influenced by the contemporary folk religion of the area.[4] According to Smith, he received his First Vision around 1820, a vision in which he said he saw and heard the voice of Jesus. Although this experience was unknown to all but a few of Smith's followers until after his death, his accounts later acquired important theological significance within the Latter Day Saint movement.[5] Joseph Smith and the other male members of the Smith family supplemented their farm income by running a local "cake and beer shop"[6] and by taking odd jobs. In particular, the Smiths made money by participating in the early New England "craze for treasure hunting".[7] Joseph claimed the ability to use seer stones for locating lost items and buried treasure.[8] To do so, Smith would put a stone in a white stovepipe hat and would then "see the required information in reflections given off by the stone".[9] In 1823, Smith said he was visited at night by an angel named Moroni, who revealed to him the location of a buried book of golden plates, as well as other artifacts including a breastplate and a set of silver spectacles with lenses composed of seer stones, hidden in a hill near his home. Smith said the angel told him this book of golden plates contained a religious record of the indigenous Americans. Smith said he attempted to remove the plates the next morning but was unsuccessful because the angel struck him down with supernatural force.[10] During the next several years, Smith said he made annual visits to Cumorah to meet with the angel, but the angel would not relinquish the plates. Meanwhile, Smith continued to travel around western New York and Pennsylvania working as a "glass looker." During one of these jobs, he met Emma Hale and married her on January 18, 1827. (Emma eventually gave birth to seven children, three of whom died shortly after birth; the Smiths also adopted twins.)[11] (See Children of Joseph Smith, Jr.) On September 22, 1827 Smith went to the hill Cumorah in a final attempt to obtain the plates. This time he said he retrieved them and placed them in a locked chest. He said the angel commanded him not to show the plates to anyone else but to publish their translation.[12] Believing they should have a share in any proceeds from the plates, Smith's treasure seeking associates began to ransack places they thought the plates might be hidden, and Smith soon realized that he could not perform this translation in Palmyra.[13] In October 1827, Smith and his wife moved from Palmyra to Harmony, Pennsylvania, with the financial assistance of their wealthy neighbor Martin Harris.[14] Smith took with them a box he said contained the golden plates. In Harmony, he began transcribing some of the characters he said were engraved on the plates, in a language he called "Reformed Egyptian." Smith said that he used the "Urim and Thummim" (the silver spectacles with lenses made of seer stones) for translation during this early period,[15] but there are no witnesses of Smith using such spectacles for translation.[16] Many witnesses did directly observe Smith translating using the same or similar method that he had previously used during his earlier profession as a treasure hunter: he would gaze at a seer stone in the bottom of his hat, excluding all light so that he could reportedly see the translation reflecting off the stone.[17] There were times when Smith concealed his translation process by, for example, raising a curtain or calling out the dictation from another room.[18] During the translation process, the plates themselves were reportedly hidden in the nearby woods.[19] By early 1828, Smith became discouraged with translating, prompting Martin Harris to visit Harmony in February 1828 to spur him on.[20] Smith allowed Harris to take some of the transcribed characters to several well-known scholars[21] to see if they could translate or authenticate them,[22] but Harris was unable to get any assistance from the scholars.[23] When Harris returned to Harmony, he acted as Smith's scribe from April 12 to June 14, 1828, until Smith had dictated 116 pages of manuscript. Acceding to relentless requests from Harris, Smith reluctantly allowed him to take the manuscript to Palmyra to assuage the growing skepticism of Harris' wife Lucy, who suspected Smith was trying to defraud her husband. When Harris returned, long overdue, he told Smith that the manuscript had disappeared. There were no copies. At about the same time, Smith's wife Emma gave birth to a stillborn son.[24] Distraught over losing both his child and the manuscript, Smith may have briefly attended a Methodist church pastored by his wife's uncle.[25] Smith also dictated a revelation stating that his gift to translate had been taken away[26] and that the angel Moroni had taken back the plates and the Urim and Thummim.[27] Nevertheless, Smith said the angel returned the Urim and Thummim (and presumably the plates) on September 22, 1828, and that he continued to translate with Emma as his scribe.[28] According to Emma, Smith never claimed to use the Urim and Thummim for translation after the loss of the 116 pages. Rather, Smith exclusively used the same dark seer stone that he had previously used during his earlier profession as a treasure hunter.[29] On April 1829, Smith met Oliver Cowdery,[30] who took over as scribe, and the two worked full time between April and June 1829 to prepare most of the translation. To Smith, the golden plates were more than just a curiosity; Smith viewed them as a "marvelous work…about to come forth among the children of men"[31] It would be entitled the Book of Mormon, and form the basis for a new religion. In early June 1829, Smith and Cowdery moved to Fayette, New York to complete the translation, and Smith began to seek converts. When people believed, "they did not just subscribe to the book; they were baptized." But as Smith "began to seek converts the question of credibility had to be addressed again. Joseph knew his story was unbelievable."[32] He had a revelation that others, known today as the Three Witnesses and the Eight Witnesses, would bear testimony to the existence of the plates—which they did in early July 1829.[33] Finally, the Book of Mormon was published in Palmyra on March 26, 1830 by printer E. B. Grandin. Martin Harris financed the publication by mortgaging his farm.[34] On April 6, 1830, Joseph Smith and his followers formally organized as the Church of Christ,[35] and small branches were established in Palmyra, Fayette, and Colesville, New York. There was strong opposition to the church, and in late June, Smith was again brought to court but acquitted.[36] Perhaps it was to this period that Smith and Cowdery referred when they later said that they had received a visitation from Peter, James, and John, three apostles of Jesus, who appeared to them in order to restore the Melchizedek priesthood, which they said contained the necessary authority to restore Christ's church.[37] After founding the church, Smith began to publicize an experience he said he had had as a fourteen-year-old in 1820, when he received a theophany, an event more recent Latter Day Saints have called the First Vision.[38] Smith recorded several different accounts of this experience,[39] but the version of the First Vision later canonized by the LDS Church was not publicly revealed until 1842. Although the experience acquired immense theological importance in Latter Day Saint belief, "most early converts probably never heard about the 1820 vision."[40] In July 1831, Smith revealed that the church would establish a "City of Zion" in Native American territory near Missouri.[41] In anticipation, Smith dispatched missionaries, led by Oliver Cowdery, to the area. On their way, they converted a group of Disciples of Christ adherents in Kirtland, Ohio led by Sidney Rigdon. To avoid growing opposition in New York, Smith moved the headquarters of the church to Kirtland.[42] Sidney Rigdon's supporters more than doubled the number of Latter Day Saints, and when the comparatively well-educated and oratorically gifted Rigdon became Smith's closest adviser, he aroused the resentment of some of Smith's earliest followers.[43] The Kirtland saints also exhibited unusual spiritual gifts such as loud prophesying, speaking in unknown tongues, swinging from house joists, and rolling on the ground. With some difficulty, Smith managed to check the most extreme forms of religious enthusiasm.[44]

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

Our Heritage: A Brief History of the LDS Church

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Our Heritage: A Brief History of the LDS Church

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Book digitized by Google from the library of Harvard University and uploaded to the Internet Archive by user tpb.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

Our Heritage: A Brief History of the LDS Church

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Our Heritage: A Brief History of the LDS Church

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Book digitized by Google from the library of Harvard University and uploaded to the Internet Archive by user tpb.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

2.5/5

Book digitized by Google and uploaded to the Internet Archive by user tpb.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Ready references : a compilation of scripture texts, arranged in subjective order, with numerous annotations from eminent writers ; designed especially for the use of missionaries and scripture students

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Printed marginal notations First published in 1884, at the Millennial Star Office Bound in blind stamped black sheep Flake, C.J. Mormon bib. Autograph of J. U.Stucki on pastedown 1 9

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Book digitized by Google and uploaded to the Internet Archive by user tpb.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints 4

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Book digitized by Google and uploaded to the Internet Archive by user tpb.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Liederbuch für die Deutsche und Schweizer-mission der Kirche Jesu Christi ...

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Book digitized by Google from the library of the New York Public Library and uploaded to the Internet Archive by user tpb.

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

A Hand-book of reference to the history, chronology, religion and country of the Latterday saints, including the revelation on celestial marriage. For the use of saints and strangers

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Book digitized by Google from the library of New York Public Library and uploaded to the Internet Archive by user tpb. Copy-righted by A.H. Cannon Mode of access: Internet

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Moral stories for little folks

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

"For Sunday schools, primary associations and home teaching"

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

- Books / History / World / Expeditions & Discoveries

- Literature & Fiction / Classics

- Biographies & Memoirs / Ethnic & National / African-American & Black

- Professional & Technical / Professional Science / Astronomy

- Religion & Spirituality / Christianity / Mormonism

- Bibliography / Early printed books / Catalogs

- Books / Mineral waters / New York (State) / Saratoga Springs

if you like Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints try:

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

- Books / History / World / Expeditions & Discoveries

- Literature & Fiction / Classics

- Biographies & Memoirs / Ethnic & National / African-American & Black

- Professional & Technical / Professional Science / Astronomy

- Religion & Spirituality / Christianity / Mormonism

- Bibliography / Early printed books / Catalogs

- Books / Mineral waters / New York (State) / Saratoga Springs

if you like Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints try:

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!