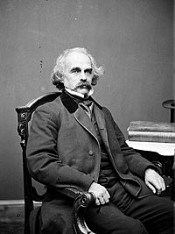

Hawthorne Nathaniel

Nathaniel Hawthorne (born Nathaniel Hathorne; July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. Nathaniel Hathorne was born in 1804 in the city of Salem, Massachusetts to Nathaniel Hathorne and Elizabeth Clarke Manning Hathorne. He later changed his name to "Hawthorne", adding a "w" to dissociate from relatives including John Hathorne, a judge during the Salem Witch Trials. Hawthorne attended Bowdoin College, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa in 1824,[1] and graduated in 1825; his classmates included future president Franklin Pierce and future poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Hawthorne anonymously published his first work, a novel titled Fanshawe, in 1828. He published several short stories in various periodicals which he collected in 1837 as Twice-Told Tales. The next year, he became engaged to Sophia Peabody. He worked at a Custom House and joined Brook Farm, a transcendentalist community, before marrying Peabody in 1842. The couple moved to The Old Manse in Concord, Massachusetts, later moving to Salem, the Berkshires, then to The Wayside in Concord. The Scarlet Letter was published in 1850, followed by a succession of other novels. A political appointment took Hawthorne and family to Europe before their return to The Wayside in 1860. Hawthorne died on May 19, 1864, leaving behind his wife and their three children. Much of Hawthorne's writing centers around New England, many works featuring moral allegories with a Puritan inspiration. His fiction works are considered part of the Romantic movement and, more specifically, dark romanticism. His themes often center on the inherent evil and sin of humanity, and his works often have moral messages and deep psychological complexity. His published works include novels, short stories, and a biography of his friend Franklin Pierce. Nathaniel Hawthorne was born on July 4, 1804, in Salem, Massachusetts; his birthplace is preserved and open to the public.[2] William Hathorne, the author's great-great-great-grandfather, a Puritan, was the first of the family to emigrate from England, first settling in Dorchester, Massachusetts before moving to Salem. There he became an important member of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and held many political positions including magistrate and judge, becoming infamous for his harsh sentencing.[3] William's son and the author's great-great-grandfather, John Hathorne, was one of the judges who oversaw the Salem Witch Trials. Having learned about this, the author may have added the "w" to his surname in his early twenties, shortly after graduating from college, in an effort to dissociate himself from his notorious forebears.[4] Hawthorne's father, Nathaniel Hathorne, Sr., was a sea captain who died in 1808 of yellow fever in Suriname.[5] After his death, young Nathaniel, his mother and two sisters moved in with maternal relatives, the Mannings, in Salem,[6] where they lived for ten years. During this time, on November 10, 1813, young Hawthorne was hit on the leg while playing "bat and ball"[7] and became lame and bedridden for a year, though several physicians could find nothing wrong with him.[8] In the summer of 1816, the family lived as boarders with farmers[9] before moving to a home recently built specifically for them by Hawthorne's uncles Richard and Robert Manning in Raymond, Maine, near Sebago Lake.[10] Years later, Hawthorne looked back at his time in Maine fondly: "Those were delightful days, for that part of the country was wild then, with only scattered clearings, and nine tenths of it primeval woods".[11] In 1819, he was sent back to Salem for school and soon complained of homesickness and being too far from his mother and sisters.[12] In spite of his homesickness, for fun, he distributed to his family seven issues of The Spectator in August and September 1820. The homemade newspaper was written by hand and included essays, poems, and news utilizing the young author's developing adolescent humor.[13] Hawthorne's uncle Robert Manning insisted, despite Hawthorne's protests, that the boy attend college.[14] With the financial support of his uncle, Hawthorne was sent to Bowdoin College in 1821, partly because of family connections in the area, and also because of its relatively inexpensive tuition rate.[15] On the way to Bowdoin, at the stage stop in Portland, Hawthorne met future president Franklin Pierce and the two became fast friends.[14] Once at the school, he also met the future poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, future congressman Jonathan Cilley, and future naval reformer Horatio Bridge.[16] Years after his graduation with the class of 1825, he would describe his college experience to Richard Henry Stoddard: I was educated (as the phrase is) at Bowdoin College. I was an idle student, negligent of college rules and the Procrustean details of academic life, rather choosing to nurse my own fancies than to dig into Greek roots and be numbered among the learned Thebans.[17] Hawthorne was offered an appointment as weighter and gauger at the Boston Custom House at a salary of $1,500 a year, which he accepted on January 17, 1839.[18] During his time there, he rented a room from George Stillman Hillard, business partner of Charles Sumner.[19] Hawthorne wrote in the comparative obscurity of what he called his "owl's nest" in the family home. As he looked back on this period of his life, he wrote: "I have not lived, but only dreamed about living".[20] He contributed short stories, including "Young Goodman Brown" and "The Minister's Black Veil", to various magazines and annuals, though none drew major attention to the author. Horatio Bridge offered to cover the risk of collecting these stories in the spring of 1837 into one volume, Twice-Told Tales, which made Hawthorne known locally.[21] While at Bowdoin, Hawthorne had bet his friend Jonathan Cilley a bottle of Madeira wine that he would not be married in 12 years.[22] By 1836 he had won the wager, but did not remain a bachelor for life. After public flirtations with local women Mary Silsbee and Elizabeth Peabody,[23] he had become engaged in 1836 to the latter's sister, illustrator and transcendentalist Sophia Peabody. Seeking a possible home for himself and Sophia, he joined the transcendentalist Utopian community at Brook Farm in 1841 not because he agreed with the experiment but because it helped him save money to marry Sophia.[24] He paid a $1,000 deposit and was put in charge of shoveling the hill of manure referred to as "the Gold Mine".[25] He left later that year, though his Brook Farm adventure would prove an inspiration for his novel The Blithedale Romance.[26] Hawthorne married Sophia Peabody on July 9, 1842, at a ceremony in the Peabody parlor on West Street in Boston.[27] The couple moved to The Old Manse in Concord, Massachusetts,[28] where they lived for three years. There he wrote most of the tales collected in Mosses from an Old Manse.[29] Like Hawthorne, Sophia was a reclusive person. Throughout her early life, she had frequent migraines and underwent several experimental medical treatments.[30] She was mostly bedridden until her sister introduced her to Hawthorne, after which her headaches seem to have abated. The Hawthornes enjoyed a long marriage, often taking walks in the park. Of his wife, whom he referred to as his "Dove", Hawthorne wrote that she "is, in the strictest sense, my sole companion; and I need no other—there is no vacancy in my mind, any more than in my heart... Thank God that I suffice for her boundless heart!"[31] Sophia greatly admired her husband's work. In one of her journals, she wrote: "I am always so dazzled and bewildered with the richness, the depth, the ... jewels of beauty in his productions that I am always looking forward to a second reading where I can ponder and muse and fully take in the miraculous wealth of thoughts".[32] Nathaniel and Sophia Hawthorne had three children. Their first, a daughter, was born March 3, 1844. She was named Una, a reference to The Faerie Queene, to the displeasure of family members.[33] In 1846, their son Julian was born. Hawthorne wrote to his sister Louisa on June 22, 1846, with the news: "A small troglodyte made his appearance here at ten minutes to six o'clock this morning, who claimed to be your nephew".[34] Their final child, Rose, was born in May 1851. Hawthorne called her "my autumnal flower".[35] In April 1846, Hawthorne was officially appointed as the "Surveyor for the District of Salem and Beverly and Inspector of the Revenue for the Port of Salem" at an annual salary of $1,200.[36] He had difficulty writing during this period, as he admitted to Longfellow: "I am trying to resume my pen... Whenever I sit alone, or walk alone, I find myself dreaming about stories, as of old; but these forenoons in the Custom House undo all that the afternoons and evenings have done. I should be happier if I could write".[37] Like his earlier appointment to the custom house in Boston, this employment was vulnerable to the politics of the spoils system. A Democrat, Hawthorne lost this job due to the change of administration in Washington after the presidential election of 1848. Hawthorne wrote a letter of protest to the Boston Daily Advertiser which was attacked by the Whigs and supported by the Democrats, making Hawthorne's dismissal a much-talked about event in New England.[38] Hawthorne was deeply affected by the death of his mother shortly thereafter in late July, calling it, "the darkest hour I ever lived".[39] Hawthorne was appointed the corresponding secretary of the Salem Lyceum in 1848. Guests that came to speak that season included Emerson, Thoreau, Louis Agassiz and Theodore Parker.[40] Hawthorne returned to writing and published The Scarlet Letter in mid-March 1850,[41] including a preface which refers to his three-year tenure in the Custom House and makes several allusions to local politicians, who did not appreciate their treatment.[42] One of the first mass-produced books in America, it sold 2,500 volumes within ten days and earned Hawthorne $1,500 over 14 years.[43] The book became an immediate best-seller[44] and initiated his most lucrative period as a writer.[43] One of Hawthorne's friends, the critic Edwin Percy Whipple, objected to the novel's "morbid intensity" and its dense psychological details, writing that the book "is therefore apt to become, like Hawthorne, too painfully anatomical in his exhibition of them",[45] though 20th century writer D. H. Lawrence said that there could be no more perfect work of the American imagination than The Scarlet Letter.[46]

do you like this author?

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this book!

write a commentWhat readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentBook list

Little MasterpiecesDr. Heidegger's Experiment,The Birthmark,Ethan Brand,Wakefield,Drowne's Wooden Image,The Ambitious Guest,TheGreat Stone F

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Our Old Home,Vol. 2Annotated with Passages from the Author's Notebook

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Book list

Little MasterpiecesDr. Heidegger's Experiment,The Birthmark,Ethan Brand,Wakefield,Drowne's Wooden Image,The Ambitious Guest,TheGreat Stone F

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Our Old Home,Vol. 2Annotated with Passages from the Author's Notebook

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

A Wonder Book and Tanglewood TalesFor girls and boys

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Miraculous Pitcher(From: "A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys")

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Three Golden Apples(From: "A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys")

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Paradise of Children(From: "A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys")

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

The Gorgon's Head(From: "A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys")

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Biographical Stories(From: "True Stories of History and Biography")

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Browne's Folly(From: "The Doliver Romance and Other Pieces: Tales and Sketches")

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Time's Portraiture(From: "The Doliver Romance and Other Pieces: Tales and Sketches")

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

An Old Woman's Tale(From: "The Doliver Romance and Other Pieces: Tales and Sketches")

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Dr. Bullivant(From: "The Doliver Romance and Other Pieces: Tales and Sketches")

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

3/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Other Tales and Sketches(From: "The Doliver Romance and Other Pieces: Tales and Sketches")

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Fragments from the Journal of a Solitary Man(From: "The Doliver Romance and Other Pieces: Tales and Sketches")

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Sketches from Memory(From: "The Doliver Romance and Other Pieces: Tales and Sketches")

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

Biographical Sketches(From: "Fanshawe and Other Pieces")

Series:

Unknown

Year:

Unknown

Raiting:

4.5/5

Show more

add to favoritesadd In favorites

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentif you like Hawthorne Nathaniel try:

Stieg Larsson

(Author)

Suzanne Collins

(Author)

J.R.R. Tolkien

(Author)

Robert Jordan

(Author)

Brandon Sanderson

(Author)

Orson Scott Card

(Author)

readers also enjoyed

What readers are saying

What do you think? Write your own comment on this author!

write a commentGenre

if you like Hawthorne Nathaniel try:

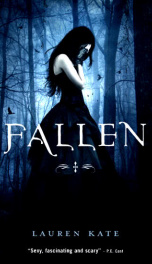

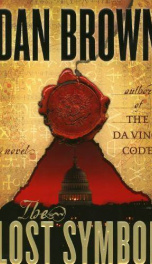

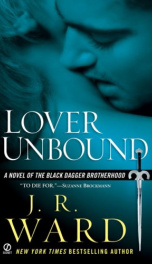

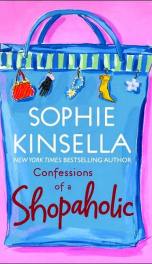

readers also enjoyed

Do you want to exchange books? It’s EASY!

Get registered and find other users who want to give their favourite books to good hands!